Lessons For Life: Helping Hand?

Helping Hand?

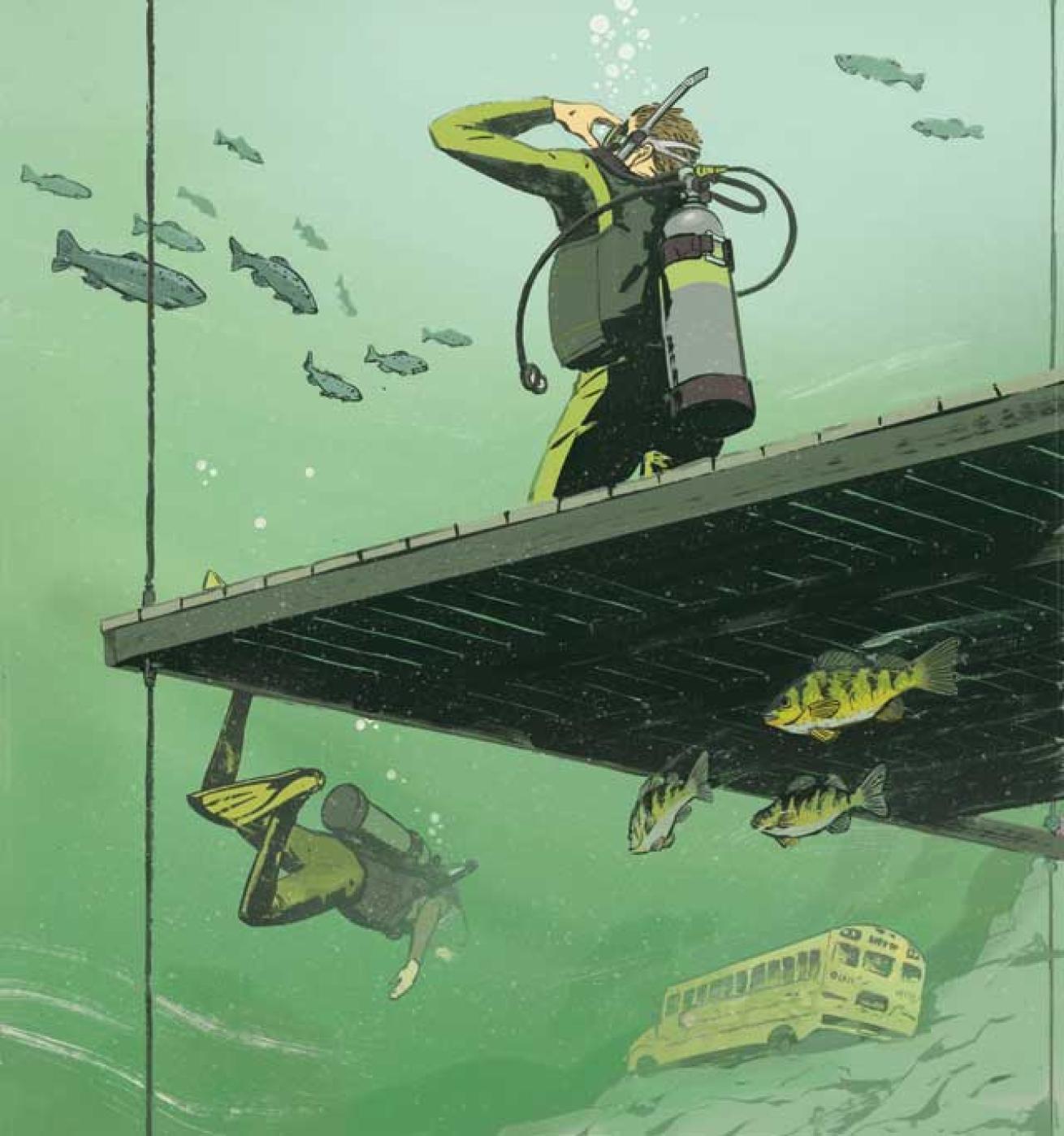

An experienced diver tries to manage a panicky newer one, with tragic results.

Jori Bolton

Tom’s dive buddy, Dave, was growing agitated. Dave’s mask kept flooding, and it was clear to Tom that Dave was about to panic. Tom tried to calm Dave down and had him kneel on a training platform on the bottom of the quarry they were diving in. He signaled to Dave to take deep, slow breaths and to relax. Then he signaled that he was going to go look for help. Dave watched as Tom turned and swam away. It was the last time anyone saw Tom alive.

THE DIVER

Most of Tom’s dives were in the local quarry where he earned his open-water and advanced certifications. At 44, he was fit and healthy with no major medical conditions.

THE DIVE

One afternoon, two instructors invited Tom along for a fun dive at the quarry. When Tom showed up at the dive site, he found out there would be four divers making the dive. The two dive instructors were going to dive together, and he was going to buddy up with Dave, a recently certified diver. Tom hadn’t dived with Dave before, but Tom figured he could help out the newer diver.

When they checked in, the quarry owner said that visibility was lower than normal due to recent rains. The foursome talked about whether to get in the water and decided to go ahead. Tom was comfortable with the dive, having spent most of his diving career in that quarry. Dave was less certain, but the presence of the other divers reassured him.

The four began the dive, working as two buddy teams.

The two dive instructors were ready first, and waved goodbye to Tom and Dave as they sank below the surface. It took Dave a few more minutes to get ready, and then he and Tom gave each other a final OK and descended. They planned to swim past the skills platform at around 30 feet, and then cruise over and into a submerged school bus. They were going to finish off the dive around the rock-crushing equipment.

THE ACCIDENT

Dave’s mask began leaking almost as soon as he submerged. He fought with it, clearing the mask again and again as they descended, but he grew more agitated and uncomfortable. Tom noticed his buddy was lagging behind, but wasn’t aware of the problem until Dave grabbed Tom’s fin and gestured to the water filling his mask. They approached the skills platform, and Tom signaled to Dave that he should kneel down while Tom looked for the problem. Tom searched for a reason the mask wouldn’t seal properly, but he couldn’t find anything.

Tom motioned that he was going to find the others to see if they could help, and then he swam off in the general direction of the sunken bus. The gloom swallowed Tom quickly. Dave stayed on the dive platform and did his best to remain calm.

A few minutes later, Dave was relieved to see a diver swimming toward him. He realized it was one of the dive instructors. Then he saw the second instructor kicking toward him. Dave assumed Tom brought them back. Dave signaled to one of the instructors that he was having a problem with his mask. After a moment of looking for a problem, the instructors signaled Dave to ascend.

At the surface, Dave realized that Tom was not with the dive instructors. They immediately began searching for Tom’s bubbles, and then exited the water to initiate a search.

Tom’s body wasn’t recovered until the next day.

ANALYSIS

Most dive accidents happen when multiple small problems and bad choices build to the point that stress kicks in and perceptual narrowing limits a diver’s choices to one: panic.

Tom’s death was ultimately ruled a drowning. Somehow, in searching for the dive-instructor buddy team, he ran out of air underwater and lost consciousness. We’ll never know what went through his mind, but presumably he got lost when he left Dave on the platform, and couldn’t find the landmarks he was looking for in the reduced visibility of the quarry. Rather than ascending to the surface, he fixated on finding the others.

The divers made several bad choices that contributed to the problem. The dive plan was for the four divers to explore the quarry together. Almost immediately, the dive instructors took off on their own, assuming that Tom and Dave were right behind them.

After trying for a moment to fix the problem with Dave’s mask, Tom and Dave should have made a slow, controlled ascent to the surface following the descent line attached to the skills platform. They could have found a way to fix the problem in the water, or aborted the dive.

In this case, the buddy separation was intentional, but it had a bad outcome for Tom. He never should have gone off on his own to look for the other divers. Once he did, he should have limited his search to a minute and then ascended to the surface, looked for the marker buoy on the platform, and then rejoined Dave to at least bring him to the surface.

Dave wasn’t comfortable with the dive, but the presence of the other divers persuaded him to go ahead. We don’t know whether peer pressure played a role, but no diver should ever make a dive that makes him or her uncomfortable. Any diver should be able to call any dive at any time for any reason.

Tom took the attitude that he could help out the less-experienced diver. At that point, Tom didn’t have a buddy, at least not one who could help out in an emergency. Tom could have cut off the cycle of problems with this dive if only he had decided to surface at any one of several opportunities. He didn’t make that decision, and he paid for it with his life.

Lessons For Life

-

Make a dive plan and stick to it. Too often divers have a general plan of “diving in the same ocean on the same day,” and then get into trouble when everyone’s experience level isn’t the same.

-

If you can’t quickly resolve a problem underwater, ascend to the surface and figure it out, or abort the dive. if the dive is deep, it is best to abort and try again later rather than make bounce dives. Unless circumstances make it impossible to surface with a buddy, never leave a buddy alone underwater.

-

If you and a buddy become separated, search the area for no more than a minute, and then make a slow, controlled ascent to the surface.

-

Don’t dive if you aren’t prepared or comfortable with the dive. if equipment issues or dive conditions make you uncomfortable, abort the dive.

-

Your panic can put your buddy in trouble. Don’t let your own situation get so out of control that your buddy has to attempt to rescue you, risking his own life.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety, and has written a series of dive-adventure novels and short stories. Check out his website at booksbyeric.com.

To read more Lessons For Life, visit the Lessons For Life section of our website.

Jori BoltonAn experienced diver tries to manage a panicky newer one, with tragic results.

Tom’s dive buddy, Dave, was growing agitated. Dave’s mask kept flooding, and it was clear to Tom that Dave was about to panic. Tom tried to calm Dave down and had him kneel on a training platform on the bottom of the quarry they were diving in. He signaled to Dave to take deep, slow breaths and to relax. Then he signaled that he was going to go look for help. Dave watched as Tom turned and swam away. It was the last time anyone saw Tom alive.

THE DIVER

Most of Tom’s dives were in the local quarry where he earned his open-water and advanced certifications. At 44, he was fit and healthy with no major medical conditions.

THE DIVE

One afternoon, two instructors invited Tom along for a fun dive at the quarry. When Tom showed up at the dive site, he found out there would be four divers making the dive. The two dive instructors were going to dive together, and he was going to buddy up with Dave, a recently certified diver. Tom hadn’t dived with Dave before, but Tom figured he could help out the newer diver.

When they checked in, the quarry owner said that visibility was lower than normal due to recent rains. The foursome talked about whether to get in the water and decided to go ahead. Tom was comfortable with the dive, having spent most of his diving career in that quarry. Dave was less certain, but the presence of the other divers reassured him.

The four began the dive, working as two buddy teams.

The two dive instructors were ready first, and waved goodbye to Tom and Dave as they sank below the surface. It took Dave a few more minutes to get ready, and then he and Tom gave each other a final OK and descended. They planned to swim past the skills platform at around 30 feet, and then cruise over and into a submerged school bus. They were going to finish off the dive around the rock-crushing equipment.

THE ACCIDENT

Dave’s mask began leaking almost as soon as he submerged. He fought with it, clearing the mask again and again as they descended, but he grew more agitated and uncomfortable. Tom noticed his buddy was lagging behind, but wasn’t aware of the problem until Dave grabbed Tom’s fin and gestured to the water filling his mask. They approached the skills platform, and Tom signaled to Dave that he should kneel down while Tom looked for the problem. Tom searched for a reason the mask wouldn’t seal properly, but he couldn’t find anything.

Tom motioned that he was going to find the others to see if they could help, and then he swam off in the general direction of the sunken bus. The gloom swallowed Tom quickly. Dave stayed on the dive platform and did his best to remain calm.

A few minutes later, Dave was relieved to see a diver swimming toward him. He realized it was one of the dive instructors. Then he saw the second instructor kicking toward him. Dave assumed Tom brought them back. Dave signaled to one of the instructors that he was having a problem with his mask. After a moment of looking for a problem, the instructors signaled Dave to ascend.

At the surface, Dave realized that Tom was not with the dive instructors. They immediately began searching for Tom’s bubbles, and then exited the water to initiate a search.

Tom’s body wasn’t recovered until the next day.

ANALYSIS

Most dive accidents happen when multiple small problems and bad choices build to the point that stress kicks in and perceptual narrowing limits a diver’s choices to one: panic.

Tom’s death was ultimately ruled a drowning. Somehow, in searching for the dive-instructor buddy team, he ran out of air underwater and lost consciousness. We’ll never know what went through his mind, but presumably he got lost when he left Dave on the platform, and couldn’t find the landmarks he was looking for in the reduced visibility of the quarry. Rather than ascending to the surface, he fixated on finding the others.

The divers made several bad choices that contributed to the problem. The dive plan was for the four divers to explore the quarry together. Almost immediately, the dive instructors took off on their own, assuming that Tom and Dave were right behind them.

After trying for a moment to fix the problem with Dave’s mask, Tom and Dave should have made a slow, controlled ascent to the surface following the descent line attached to the skills platform. They could have found a way to fix the problem in the water, or aborted the dive.

In this case, the buddy separation was intentional, but it had a bad outcome for Tom. He never should have gone off on his own to look for the other divers. Once he did, he should have limited his search to a minute and then ascended to the surface, looked for the marker buoy on the platform, and then rejoined Dave to at least bring him to the surface.

Dave wasn’t comfortable with the dive, but the presence of the other divers persuaded him to go ahead. We don’t know whether peer pressure played a role, but no diver should ever make a dive that makes him or her uncomfortable. Any diver should be able to call any dive at any time for any reason.

Tom took the attitude that he could help out the less-experienced diver. At that point, Tom didn’t have a buddy, at least not one who could help out in an emergency. Tom could have cut off the cycle of problems with this dive if only he had decided to surface at any one of several opportunities. He didn’t make that decision, and he paid for it with his life.

Lessons For Life

Make a dive plan and stick to it. Too often divers have a general plan of “diving in the same ocean on the same day,” and then get into trouble when everyone’s experience level isn’t the same.

If you can’t quickly resolve a problem underwater, ascend to the surface and figure it out, or abort the dive. if the dive is deep, it is best to abort and try again later rather than make bounce dives. Unless circumstances make it impossible to surface with a buddy, never leave a buddy alone underwater.

If you and a buddy become separated, search the area for no more than a minute, and then make a slow, controlled ascent to the surface.

Don’t dive if you aren’t prepared or comfortable with the dive. if equipment issues or dive conditions make you uncomfortable, abort the dive.

Your panic can put your buddy in trouble. Don’t let your own situation get so out of control that your buddy has to attempt to rescue you, risking his own life.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety, and has written a series of dive-adventure novels and short stories. Check out his website at booksbyeric.com.

To read more Lessons For Life, visit the Lessons For Life section of our website.