The Real-Life Superheroes of Scuba Diving

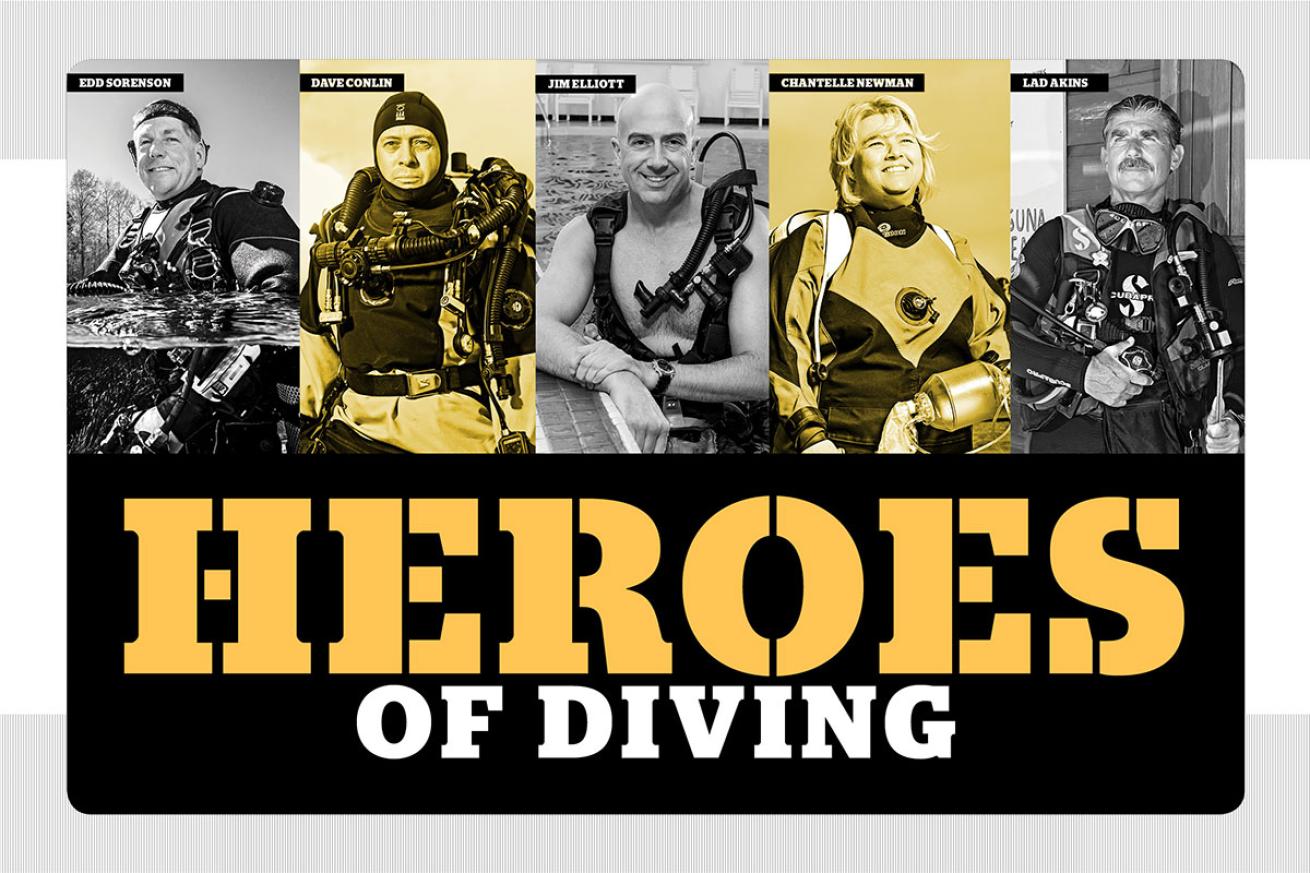

Photo Illustration by Monica AlbertaHeroes of Diving

What inspires a diver to decide to make our shared passion a personal mission, to devote a life to service to his or her fellow man — or the planet — through diving? Meet five scuba diving heroes who did just that.

Photo By Jennifer IdolCave rescue scuba diver Edd Sorenson goes deep into flooded caves to save and recover people who get trapped inside.

Edd Sorenson | Cave Rescue & Recovery Diver

Edd Sorenson has a reputation as a cave diver who will go places no other diver will go, slipping through seemingly impassable cracks deep inside flooded caves. “I don’t know how I do it,” he says. “I’ve been into stuff so small that my head won’t fit, and I have to turn my head sideways. I’m not very smart I guess, but I just won’t give up.”

It’s that same tenacity that has given him another reputation: the world’s most successful cave rescue diver. The cold reality of cave diving is that rescue is exceedingly rare. When a diver gets lost in a cave, the search teams expect to come out with a body. In 2012, there had been only four successful rescues in the history of cave diving. Since then, Sorenson has saved four more.

Four is the only number he tries to remember. “I don’t remember how many recoveries there have been, just flashes of incidents over the years,” he says, recounting more than 15 years of recovery diving. Sorenson was an original member of International Underwater Cave Rescue and Recovery (IUCRR), a volunteer organization started in 1999 to protect police and fire dive teams that were often asked to perform recoveries in overhead environments even if they didn’t have the training for it.

“I found him breathing from a small air pocket of his own exhaust bubbles — 30 seconds later, he would’ve been dead.”

But the rescues remain etched into his mind. The first was a woman who had been in a cave with her father and brother. “When we got the call, she’d been gone for 45 minutes,” he says. “My crew is amazing. They had my boat and gear ready within 30 minutes, and we made it in time to save her. It’s a pretty emotional thing when that happens.”

On another successful rescue, Sorenson made it to the diver just in time. “I found him breathing from a small air pocket of his own exhaust bubbles,” Sorenson says. “He was literally passing out from the CO2 as I caught him — 30 seconds later, he would’ve been dead.”

For Sorenson, being on call for rescues and recoveries is purely a public service, done without compensation to support first responders who don’t have cave experience, and to provide closure to the families whose loved ones get lost.

After his first successful rescue, the woman’s father tried to pay Sorenson for saving his daughter. “I told him that I don’t do it for money, and that just the week before another father was thanking me for bringing his son’s body home,” Sorenson says. “The fact that we got her back alive is more than worth it.”

Photo By Shawn JacksonLionfish hunting in the Florida Keys and scuba diving for REEF fish identification are a few of conservationist and Sea Hero Lad Akins' favorite things.

Lad Akins | Educator & Marine Conservationist

Lad Akins first got certified when he was 21 years old. It was 1982, when diving in the Florida Keys was a world apart from today. “The marine sanctuary didn’t exist. You didn’t see goliath grouper anywhere because of spearfishing,” Akins says. “Now in these same areas, we might see groups of 40 or more on one dive site.”

That change in diver mentality happened thanks, in large part, to Akins and the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF), which Akins has been a part of practically since the beginning. Founders Ned DeLoach and Paul Humann started REEF in 1990 with a plan to get divers engaged with the ocean environment through fish identification. Akins was working as a dive instructor for Spencer and Amy Slate when DeLoach and Humann came on the boat to test their idea.

“They told us to write down as many fish as we could find,” Akins says. “I thought it was a silly idea until halfway through, when I found myself searching like it was a treasure hunt, trying to find new species.”

“Lionfish are the poster child for what goes wrong when you release your pets.”

Akins was hooked. He joined DeLoach and Humann as REEF’s founding executive director to help evangelize this new approach to diving. “They were pioneers in applying a bird-watching ethos to the underwater realm,” he says. “It was personally gratifying and fun, but it also contributed to conservation.”

Then, 15 years later, something happened that would significantly change Akins’ mission. “It was around 2005 when populations of lionfish started increasing in the Carolinas and showing up in the Bahamas,” Akins says of the voracious invasive species that can decimate a reef. “In 2006, we were approached by NOAA to work with them gathering info on lionfish.”

Realizing this invasion was an environmental disaster in the making, Akins stepped down as REEF’s executive director to become director of special projects, and focus primarily on studying and controlling these invasive fish. In 2014, he was also honored as a Sea Hero.

“Lionfish are the poster child for what goes wrong when you release your pets,” Akins says. Any diver who has visited the Caribbean in the past few years has likely seen lionfish — and the efforts at control. Akins has been at the forefront, helping marine parks create management plans, and teaching divers and dive centers throughout the region how to collect them.

“We helped organize the first lionfish derby,” Akins says. “Now there are derbies all around the region, and we’re finding that local control can be very effective in keeping populations down on dive sites.” In the Keys, REEF has trained around 800 divers to collect lionfish. “It’s very unlikely that you’ll see a lionfish in the Florida Keys these days.”

Photo By Daniel BedellUnderwater archaeologist Dave Conlin works to protect and preserve historical underwater artifacts including the WWII shipwrecks in Pearl Harbor.

Dave Conlin | Underwater Archaeologist

Underwater archaeology has fascinated Dave Conlin since he was a child scouring National Geographic and watching The Jacques Cousteau Odyssey for shipwreck stories. At university, he worked on projects in Port Royal, Jamaica, and Bermuda; he earned his first master’s degree in Aegean and underwater archaeology from Oxford.

Despite spending summers sailing around Greece studying Bronze Age maritime trade and working with the U.S. Navy to excavate the Confederate submarine Hunley, the mission that most inspired him was working for the ]National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center](https://www.nps.gov/subjects/underwater/index.htm) (SRC). “The most interesting, forward-thinking underwater archaeology was done by the NPS,” he says. “I knew I wanted to work with them.”

“Some people think the NPS is trying to take shipwrecks away from divers, but there are only three sites closed to diving: USS Arizona, USS Utah and HMS Fowey.”

Conlin joined the SRC in 2000; when its founder retired in 2009, he took over as chief. The SRC is a tight-knit team of underwater archaeologists with expansive dive training that allows them to go anywhere they need to go in order to study and preserve cultural artifacts underwater. “We dive to get to do our jobs,” he says. “So we train to the point where diving comes so naturally, we don’t have to think about it.”

Among their highest-profile projects are the USS Arizona and USS Utah wrecks in Pearl Harbor, but their work takes them all over the world, from Micronesia to Mozambique. The SRC is currently working with the Smithsonian to study slave-trade wrecks off Africa.

“It’s a dark chapter in history that hasn’t been written about much because it was shameful even at the time,” Conlin says. “We’re finding small pieces of jewelry, shackles — the iron ballast is especially poignant because it makes you realize people take up a lot of room on a ship but don’t weigh much.”

Conlin and his team are driven by a commitment to preserve these resources for the public. “Some people think the NPS is trying to take shipwrecks away from divers, but the truth is, there are only three sites closed to diving in the entire park system: USS Arizona, USS Utah and HMS Fowey,” an 18th-century British warship in Biscayne National Park. “Every other plane, shipwreck and structure is open to diving, and part of our job is to fight on behalf of divers to keep those areas open.”

Photo By Taylor CastleFounder of Diveheart, a non-profit dive-training agency for adaptive scuba diving, Jim Elliott has dedicated his life to using scuba diving to benefit medical conditions.

Jim Elliott | Disabled Scuba Diver Advocate

Jim Elliott spent a lot of time in Veterans Administration hospitals, growing up the son of a disabled veteran. Then his oldest daughter was born blind, which inspired him to become a skiing instructor to the blind in the 1980s. Combine that with a long history of service with groups like the Shriners and Lions Club, and a passion for scuba diving ignited in college, and it’s not surprising that Elliott went on to start Diveheart, one of the world’s largest nonprofit organizations dedicated to introducing disabled children, adults and veterans to the sport of diving.

Elliott had risen to the upper echelons of the media industry in Chicago, working with the Chicago Tribune and launching the TV station CLTV. But he left it all behind, along with a six-figure salary, to helm his volunteer organization. “I don’t draw a salary doing this,” he says. “But I can’t imagine going back now.”

”People with multiple sclerosis have experienced pain relief. We had divers with PTSD whose symptoms were eliminated.”

Today, Elliott has turned Diveheart into a dive-training agency in its own right, with its adaptive scuba-training program. “We work with all the dive agencies to teach adaptive certifications,” Elliott says. He is passionate about helping researchers study how scuba diving and zero-gravity therapy can benefit a wide range of medical conditions.

“We did a pilot study in the Caymans and found that, at 66 feet, we get a boost of serotonin that helps with pain management,” Elliott says. “People with multiple sclerosis have experienced pain relief. We had divers with PTSD whose symptoms were eliminated. And pressure therapy might even help with autism.”

Elliott remains hands-on, traveling frequently to offer introductory programs, and organizing more disabled diving trips than any other organization.

One of his favorites was working with Korean War veteran Gabe Spataro, who helped bring the Christ of the Deep statue to Key Largo but had never dived it. Spataro, 81, had become blind and was being treated at a VA hospital. “I called up Rainbow Reef Dive Center — they cleared eight spots on a boat and got us out there.”

Photo By Tom ParkerWomen Divers Hall of Fame honoree and Scuba Medic Chantelle Newman helped develop a Diver Medic Technician course for commercial divers and adapted it for recreational diving too.

Chantelle Newman | Diver Medic Course Creator

Growing up in South Africa, Chantelle Newman started diving at age 13, making her the youngest female NAUI-certified diver at the time, though she remained uneasy about going in the water. “I was scared of things that might bite me,” she says. In her late teens, Newman started working with an ambulance service, but it was almost 20 years later, while living in the U.K., that she found her true passion by combining these two pursuits.

After hearing stories of dive accidents and realizing that many divers didn’t really understand how to deal with them, Newman started a Facebook group in 2010 called the Diver Medic. “I wanted to help improve the safety levels, knowledge and skills of divers who might get in trouble or have an accident,” she says. “Now we have almost 9,000 members in a closed group on Facebook, all related to diving accidents and safety.”

“I wanted to help improve the safety levels, knowledge and skills of divers who might get in trouble or have an accident.”

The Facebook group was only the beginning. Within a couple of years, Newman developed a Diver Medic Technician (DMT) course accredited by the International Marine Contractors Association (IMCA), which represents commercial divers. But she also wanted to extend it to recreational divers. “There are more deaths in recreational diving than commercial diving,” she says. “All of our dive agencies are ungoverned, so accidents can happen from lack of experience or because divers don’t declare certain conditions on their medical history.”

Newman worked with DAN Europe to get its accreditation for the DMT course, and she went on to become a DAN Europe training committee adviser. “People started recognizing me as a pioneer for dive safety.” This year, she was one of six women inducted into the Women Divers Hall of Fame.

Newman continues to develop additional courses and is working on ways to educate general practitioners about what they should look for before saying a patient is safe to dive. And she’s trying to improve safety conditions for divers in places that need them — one project provided medical equipment to a remote dive facility on Ascension Island. “On any dive site or boat, there should be someone with these skills on board,” she says.