Scuba Diving Newfoundland's Bell Island Mine

Newfoundland's Bell Island Mine is a time capsule of a Canadian isle's heroic struggle to support a mighty war effort while protecting a now-lost culture and way of life. Today an intrepid group of explorers paves the way for more scuba divers to experience the mine's watery depths. While their own dives yield data that could help keep all divers safer from decompression accidents.

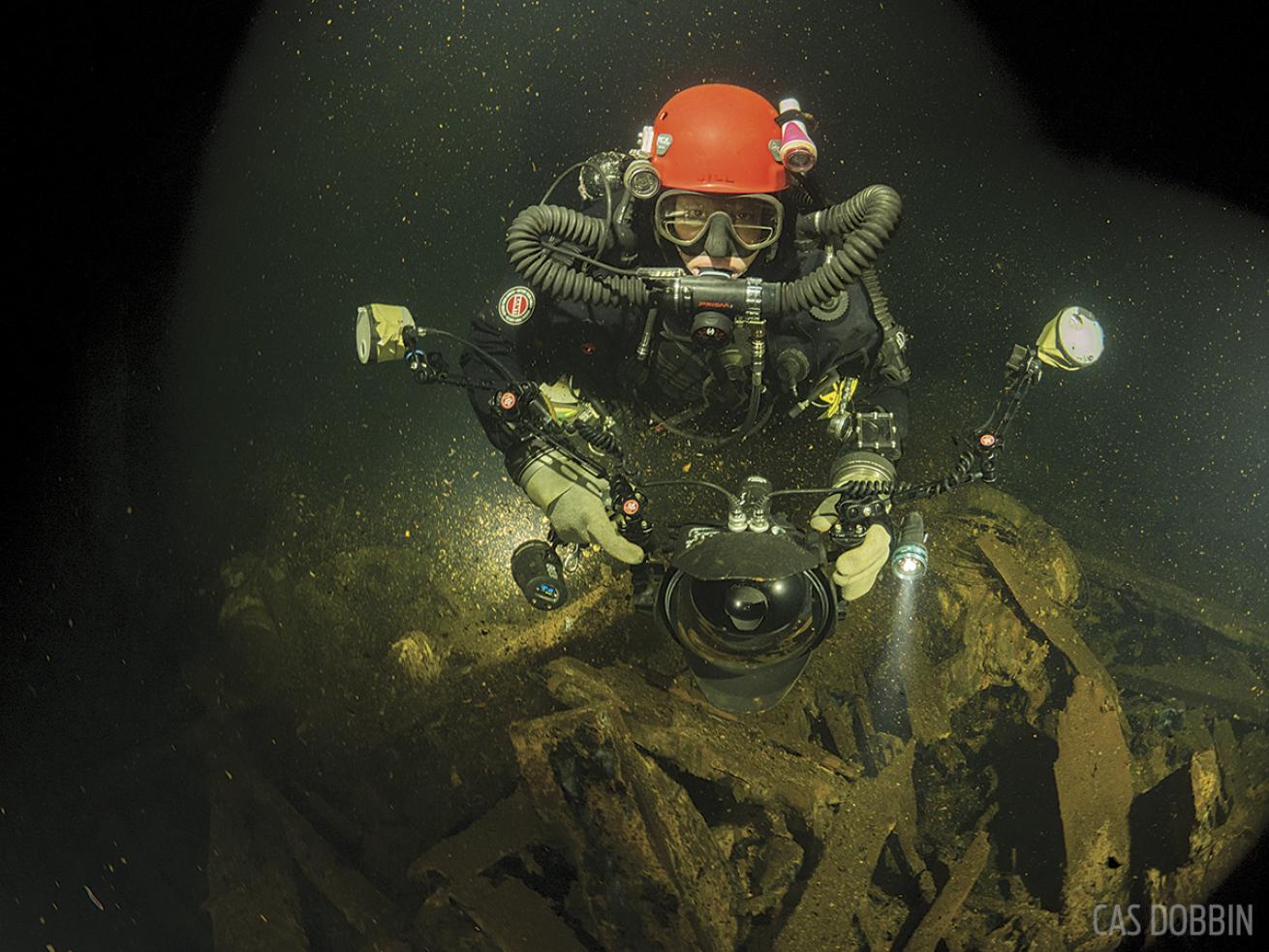

Cas DobbinAuthor Jill Heinerth — explorer in residence for the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, a sponsor of the Bell Island project — hovers over derelict equipment in the mines, which soon might be open to recreational scuba divers.

- Click here to jump to travel info for Bell Island Mine

In the pale light of a wintry Newfoundland dawn, a bone-chilling Arctic blast persuades me to snug my toque securely down over my ears. Buried deep in the neck of my parka, my muffled breath emits curly wisps of white vapor into the abruptly cold air.

Clad in not much more than a long-sleeve T-shirt, strapping, severely underdressed John Olivero vaults clear of his truck, announcing, “Let’s go diving!”

Disbelief hijacks my strong Canadian resolve. “First we have to get out of the driveway, Johnny!”

“No problem!” He smiles. “We have a secret weapon.”

Who would have imagined a scuba diving expedition that required a snowplow? The list of necessary tools grows even more peculiar. Olivero and Ocean Quest Adventure Resort owner Rick Stanley have been stockpiling pickaxes and shovels for months, and wrangling volunteers to help prepare for our visit. The group has moved tons of iron ore, built decks and benches, and installed critical lighting in preparation for our dive into the depths of the Bell Island Mine.

Newfoundland is not the first destination that comes to mind when planning a dive vacation. It’s probably not even in most divers’ top 20 — yet. The easternmost precipice of North America is the outlier of Canada’s Atlantic frontier. The independent vibe of this place is inspiring — strong, free and a little bit quirky. Living life in geographic and meteorologic extremes breeds a true sense of community. You can’t leave this place a stranger.

Sandras SpurrellJill Heinerth and Gemma Smith are helped with preparation for their dive into Bell Island Mine by Mark McGowan.

Courtesy Bell Island Historical SocietyMiners begin their long journey —more than two miles — down the main slope of the mine in 1955.

We’re in Newfoundland to reveal some of its hidden geography — historic iron mines that descend more than 1,800 feet beneath Bell Island. Now filled with water, the mines were once the economic engine of the area; by 1923, Bell Island was the second-largest community in Newfoundland, providing extremely high-grade iron ore to shipbuilding efforts in both World Wars. Recognizing the strategic importance of the mines, Germany twice sent U-boats to raid the island in 1942. The Germans knew that if they could disrupt the flow of ship-building materials, even temporarily, Allied war efforts would be seriously affected.

In two separate attacks, German submariners sank the SS Saganaga and SS Lord Strathcona, followed by the SS Rose Castle, and the Free French vessel PLM 27, while destroying the ore-loading wharf on Bell Island. In all, 70 men were killed, and the sheer temerity of the attack alerted North Americans that they were now on the front line of the Battle of the Atlantic. These massive vessels, now sitting intact at 80 to 150 feet, rival some of the most beautifully decorated wrecks in the world.

Part of the mine closed not long after WWII due to a decline in the market value of ore. Then the economic hammer slammed down hard over the Christmas holidays in 1966. When miners returned to work in the bitter cold of January, they discovered that their workplace was full of water. Determining that extraction was no longer feasible, the owners had pulled the plug on the dewatering pumps and let the vast network of tunnels slowly fill, leaving the entire island in jobless despair.

The remaining dry sections of Bell Island collected cobwebs until a modest museum opened at the entrance to the No. 2 mine. Offering walking tours of the first 650 feet down to the waterline, guides kept their family histories alive telling stories about the more than 100 men who died in the course of their work there.

Jill HeinerthTeam member John Olivero floats over a discarded bucket in Bell Island Mine.

Jill HeinerthPart of the dewatering mechanisms, at 135 feet.

IN THE BELLY OF THE BEAST

My dive buddy, Cas Dobbin, emerges from heavy silt that has obscured visibility near our entry point. The haze of iron ore mixed with melting snow and runoff eases as we descend, following iron tracks down the main shaft. The squared-off walls are marked with large white figures enumerating every crossing rib in this maze of hematite ore that descends 1 foot with every body length we swim. Seventeen feet above the floor, electrical wiring with bright turquoise insulators and wooden crossbars lead us toward some of the massive machinery that once kept this place dry.

We swim over a crumpled bucket and a pair of old leather shoes, a discarded soda bottle, and broken shovels and saws. Nobody bothered to take an inventory before they deemed this place extinct. What remains is a time capsule preserving the demoralizing moment of desperation when the pumps were turned off .

We turn a corner, gliding over the chassis of an ore cart to reach a large dewatering pump. A hulking, crippled wheel connects to long-silent gears with broken pistons that supply severed pipelines. An inscription on the wall catches our attention. “James Bennett” has scrawled his name beside a cartoonish caricature sporting a small pipe and watchman’s cap — I envision this man taking a smoke break in the dank, dust-filled darkness. A nearby tangle of rusty box springs might be evidence that he also took a few covert naps as well.

Around the next corner, we pause at another epitaph. A tiny white cross adorns the wall in a place where a miner lost his life. Was it a fall of rock or did he get run over by a cart racing through the darkness on the narrow track? It was a tough business, and hardly a family was spared from loss. If you didn’t lose a loved one in the mine, you probably have a family tale about the nights German torpedoes brought the war to your doorstep.

Jill HeinerthTeam member Cas Dobbin pauses to reflect in a spot where a miner lost his life, indicated by the small white cross that can be seen on the mine wall, to the left of the remains of the ladder.

Courtesy Bell Island Historical SocietyA Bell Island miner in an undated photo.

OLD STORIES, NEW DATA

Our project has been chosen as the Expedition of the Year by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society and granted a flag from the Explorers Club, but we are not interested in merely telling stories of the past. Researchers are also assessing our bodies to reveal how we respond to decompression stress on repetitive and lengthy cold-water dives. Dr. Neal Pollock, former research director for Divers Alert Network (now research chair in hyperbaric and diving medicine at Laval University in Quebec), heads the team.

After each dive, we shed our gear as quickly as possible to meet with Pollock and researcher Stefanie Martina, who have set up a makeshift lab in the mine museum. They poke, prod and examine us with 3-D heart ultrasounds every 20 minutes, plus blood draws and swabs that might offer evidence about how decompression stress can reprogram humans at a genetic level. We decide to let the cameras roll on our private medical evaluations, and subject ourselves to the rigors of fitness testing, fat calipers and pulmonary function tests, with our teammates cheering us on. I exhale deeply into an incentive spirometer while Martina encourages, “Blow, blow, blow, you can do it, good job.” She notes elasticity, fatigue and any possible restrictions in my lungs and how their overall function might be deteriorating and/or recovering throughout this project.

The battery of tests continues for two hours after each excursion, coupled with questionnaires about workload, thermal comfort and artificial heat sources, to help substantiate hypotheses about how the use and intensity of heated undergarments might contribute to decompression stress. With tests completed, I do it all again, preparing my rebreather and camera, and heading back down the shaft.

Jill HeinerthDobbin and John Olivero swim down the dewatering pumps, which descend one foot of depth for every 6 feet traveled into the mine.

Courtesy John OliveroJill Heinerth and Dr. Neal Pollock at the easternmost point of Canada, with the flag of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society.

PAST IS PROLOGUE

The goals of our project are simple: Lay permanent guide lines to create popular routes, map the locations of significant artifacts, and offer logistical advice for future dive operations.

But for me, this project is also about creating a visual legacy. My goal is to document this industrial archaeology, and offer photos and video assets to the Bell Island Historical Society to help plant a seed that opens future economic opportunities for these generous people, one that will share the assets of eco and cultural tourism with the world.

Our team concludes with a series of presentations at local schools. We set up our dive gear in one gymnasium too spacious for the few kids who remain. The population is one-fifth what it was, and yet the space is filled with vibrating energy — there are not many presentations like this on Bell Island. After a slide show and hands-on time with gear, we casually talk to the children about their vision of the future.

Although most will leave the island one day, some are discovering their sense of place here on Bell Island. I talk with Daniel Rees, whose grandmother rescued sailors during the 1942 sinkings. He’s working on his studies as a marine archaeologist and asks to have his photo taken with the flag of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. A small boy walks up to us and enthusiastically connects to young Daniel, then offers a simple statement that lets me know we have accomplished our work. “I didn’t know we were important. I didn’t know Bell Island mattered.”

Jill HeinertTeam member Cas Dobbin on the wreck Lord Strathcona.

NEED TO KNOW

What It Takes At Bell Island Mine all scuba divers are escorted into the mine, briefed and supported by local safety staff. Certified cave divers can file an independent dive/exploration plan; Intro/Basic Cave-qualified divers may participate in guided dives. Landlubbers can enjoy a fascinating tour of the No. 2 Mine and Museum.

When to Go June through September, with the best weather and wildlife in late June and early July

Dive Conditions Near- freezing temps on the bottom and up to 50°F on the surface for Bell Island’s wrecks, which are sheltered from all but the worst weather; the mine water temp is 40°F plus, accessible year-round in all weather.

Operator Ocean Quest Adventure Resort, Newfoundland and Labrador’s only full-service dive and adventure business, with packages and daily recreational or full technical excursions to the mines, Bell Island wrecks, Iceberg Alley, and snorkel trips to swim with humpbacks in summer. Its 42-foot cruiser Mermaid offers a large transom elevator lift; a sizable, warm enclosed space; and a full galley supplying the best onboard soup you’ll find anywhere.

Price Tag It’s $2,800 for a five-day, full technical/rebreather diving package that includes wreck and/or mine diving, gases, CCR sorb, and accommodations in a cozy and well-appointed lodge.

Jill HeinerthPartly buried tracks in Bell Island Mine at an area called Grebe's Nest.

Courtesy Rick StanleyCheck out these underwater photography tips to capture the history of Bell Island.

5 Tips for Shooting Bell Island

1 Protect your camera from getting warm between dives or you might find fog in the housing on descent. Wrap your camera in a cool towel or place in a cold-water rinse bucket.

2 Make sure you can operate your camera while wearing thick gloves. Preset and test as many functions as possible before descending

3 Carefully angle strobes and lights to prevent backscatter in the nutrient-rich ocean or silt-laden mine water.

4 Get additional lighting or strobes off the camera and into your buddy’s hands to further minimize backscatter issues.

5 Swim and shoot into the current to capture the large, open anemones on the wrecks.