Ask an Expert: Is Manipulating Marine Life Ever OK?

Ask and Expert

Ludovik Galko-Rundgren

_Is Manipulating Marine Life Ever OK?

_Conservation agencies say no, so why do so many divers do it anyway?__

Safety — yours and ocean creatures’— is just the first reason to keep your hands to yourself

****By Ocean Portal staff,

**The Smithsonian Institution******

You’ve heard it since childhood: “Look, but don’t touch!”

Chances are, you heeded that warning. But now that you’ve grown up, you don’t have to listen to anyone — or something like that.

So why shouldn’t you move a shell to get the perfect photo, or poke your finger in a hole just to see what you’ll find? The Ocean Portal team can think of several reasons why that’s not the brightest move.

First and foremost, your safety. You put your fingers in harm’s way when you stick them into unknown holes. It could be empty, but it also could be the home of a crab, moray eel or some other stinging, biting or toxic ocean animal hidden away in a crevice.

Second, when diving, you are a visitor. Without real fins or gills, we humans are often clunky and fumbling in the ocean, and some underwater creatures are more fragile than they seem. Coral polyps and sponges can be mushed with the lightest touch of a finger.

Third, the ocean is a mysterious place — even to the scientists who study it — and you never know what the consequences of your actions might be. An animal might be in that shell you just picked up, hiding from a predator. Or that fish you poked at in the anemone might have been waiting for the right moment to grab a bite to eat.

Fourth, the ocean is a pretty resilient place, but even if what you do as an individual is minor, multiplied by many visitors, the effects can be quite large.

The last reason — but certainly not the least — is that you never know when touching or moving a certain animal or plant might just be illegal. The U.S. Endangered Species Act clarified the definition of “harm” to a listed species in 1999 as “any act which actually kills or injures fish or wildlife, and […] such acts may include significant habitat modification or degradation that significantly impairs essential behavioral patterns of fish or wildlife.”

Most of us can recognize a manatee — protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act — and know to keep our distance when admiring these beautiful animals (though some might need reminding that touching, much less trying to ride them, is not allowed).

But for other animals and plants, it might not be so obvious that they are protected by law. With animals large and small, it’s best to look with our eyes, not with our hands.

Divers arrive for a shark feed with unfounded fears and leave with a new dedication to conservation

****By Cristina Zenato****

When I was approached on this subject, as a diver who feeds sharks, it was assumed I would be fully on the side of “yes.”

I wish it were so easy. After nearly 20 years of feeding and working with sharks in my area, and traveling to many distant locations to watch feeding and interaction by different operations and feeders, my answer is usually very cautious.

I do believe that some feeding in a controlled manner and with strict procedures is possible. Years of work have shown that many sea creatures exposed to such human interaction never cross the boundary between feeding time and how they assess divers without food.

Sharks are a good example. When people accuse me of “teaching” sharks to attack divers, I remind them that sharks have learned to feed from human boats, fishing lines and spears from the first day our species entered the water to procure food for ourselves. If sharks truly associated humans with food, in the Bahamas we would never be able to go snorkeling or free diving. Every single shark in our waters would have learned by now to approach and attack each person in the water. Yet spearfishermen — who often lose their catch to sharks — are the first to tell you that they can be swimming for hours, looking for prey without seeing a shark, and as soon as they spear a fish, a shark appears out of nowhere to steal it. Where was that animal all along?

We have also learned, through trial and error, that some creatures are better left alone. Feeding is a serious and potentially dangerous act; I know this and appreciate it. I am a firm believer in procedures, safety and protocol. Behind the feeding work, which might look easy, there are procedures for control of the food, and evacuation of divers, and massive team work by trained professionals.

I have seen the positive results of my and other facilities’ work: Divers arrive with an unfounded fear of sharks and leave with a newfound knowledge, with some questions answered and with the desire to protect these animals. Last and not least, we provide a financial reason for everybody in the tourism industry to keep the animals alive.

A perfect example, right on my door step: Where once there was an operation that fished sharks, now we have three glass bottom boats coming over the site three times daily to show the public the beauty of these live creatures, and shark fishing has disappeared from local tours. Feeding, when done responsibly, can have positive results, but in general, I would leave it to professionals and to established facilities.

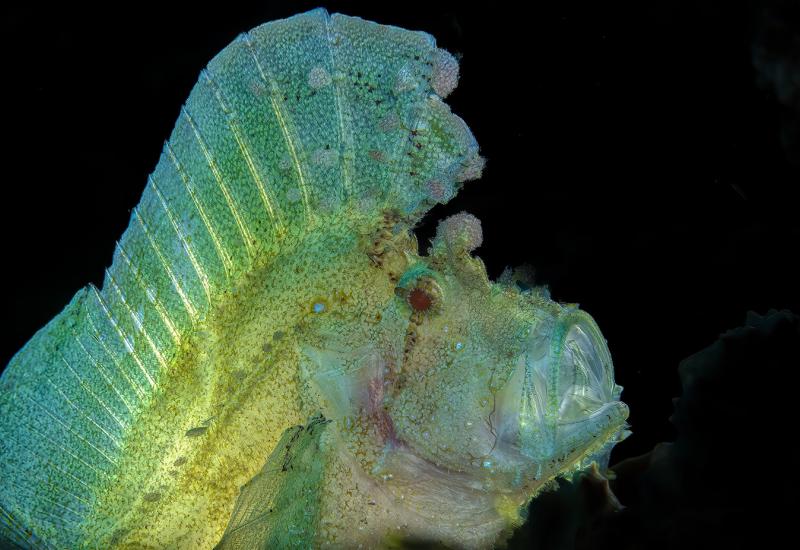

Ludovik Galko-RundgrenDivers are advised to avoid touching marine life in order to prevent both parties from harm.

Safety — yours and ocean creatures’— is just the first reason to keep your hands to yourself

By Ocean Portal staff,

The Smithsonian Institution

You’ve heard it since childhood: “Look, but don’t touch!”

Chances are, you heeded that warning. But now that you’ve grown up, you don’t have to listen to anyone — or something like that.

So why shouldn’t you move a shell to get the perfect photo, or poke your finger in a hole just to see what you’ll find? The Ocean Portal team can think of several reasons why that’s not the brightest move.

First and foremost, your safety. You put your fingers in harm’s way when you stick them into unknown holes. It could be empty, but it also could be the home of a crab, moray eel or some other stinging, biting or toxic ocean animal hidden away in a crevice.

Second, when diving, you are a visitor. Without real fins or gills, we humans are often clunky and fumbling in the ocean, and some underwater creatures are more fragile than they seem. Coral polyps and sponges can be mushed with the lightest touch of a finger.

Third, the ocean is a mysterious place — even to the scientists who study it — and you never know what the consequences of your actions might be. An animal might be in that shell you just picked up, hiding from a predator. Or that fish you poked at in the anemone might have been waiting for the right moment to grab a bite to eat.

Fourth, the ocean is a pretty resilient place, but even if what you do as an individual is minor, multiplied by many visitors, the effects can be quite large.

The last reason — but certainly not the least — is that you never know when touching or moving a certain animal or plant might just be illegal. The U.S. Endangered Species Act clarified the definition of “harm” to a listed species in 1999 as “any act which actually kills or injures fish or wildlife, and […] such acts may include significant habitat modification or degradation that significantly impairs essential behavioral patterns of fish or wildlife.”

Most of us can recognize a manatee — protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act — and know to keep our distance when admiring these beautiful animals (though some might need reminding that touching, much less trying to ride them, is not allowed).

But for other animals and plants, it might not be so obvious that they are protected by law. With animals large and small, it’s best to look with our eyes, not with our hands.

Divers arrive for a shark feed with unfounded fears and leave with a new dedication to conservation

By Cristina Zenato

When I was approached on this subject, as a diver who feeds sharks, it was assumed I would be fully on the side of “yes.”

I wish it were so easy. After nearly 20 years of feeding and working with sharks in my area, and traveling to many distant locations to watch feeding and interaction by different operations and feeders, my answer is usually very cautious.

I do believe that some feeding in a controlled manner and with strict procedures is possible. Years of work have shown that many sea creatures exposed to such human interaction never cross the boundary between feeding time and how they assess divers without food.

Sharks are a good example. When people accuse me of “teaching” sharks to attack divers, I remind them that sharks have learned to feed from human boats, fishing lines and spears from the first day our species entered the water to procure food for ourselves. If sharks truly associated humans with food, in the Bahamas we would never be able to go snorkeling or free diving. Every single shark in our waters would have learned by now to approach and attack each person in the water. Yet spearfishermen — who often lose their catch to sharks — are the first to tell you that they can be swimming for hours, looking for prey without seeing a shark, and as soon as they spear a fish, a shark appears out of nowhere to steal it. Where was that animal all along?

We have also learned, through trial and error, that some creatures are better left alone. Feeding is a serious and potentially dangerous act; I know this and appreciate it. I am a firm believer in procedures, safety and protocol. Behind the feeding work, which might look easy, there are procedures for control of the food, and evacuation of divers, and massive team work by trained professionals.

I have seen the positive results of my and other facilities’ work: Divers arrive with an unfounded fear of sharks and leave with a newfound knowledge, with some questions answered and with the desire to protect these animals. Last and not least, we provide a financial reason for everybody in the tourism industry to keep the animals alive.

A perfect example, right on my door step: Where once there was an operation that fished sharks, now we have three glass bottom boats coming over the site three times daily to show the public the beauty of these live creatures, and shark fishing has disappeared from local tours. Feeding, when done responsibly, can have positive results, but in general, I would leave it to professionals and to established facilities.