Mysteries Of The Underworld

I'm 130 feet down in the throat of Belize's most famous dive site-the Blue Hole-when a feeling of childhood deja vu creeps into my head. Maybe it's the two-story-tall stalactites hanging from the grotto walls like King Kong's fangs, maybe it's the ripped bull sharks that always seem to appear in the green fog behind me like ghostly gatekeepers. Or maybe it's the fact that the ancient Maya believed caves like this were the portals to their underworld, Xibalba.

I know this place. It is torn from the pages of my favorite childhood story about naughty Max, who, when sent to his room, conjured up a surreal world where bedroom walls melted into vine-draped jungles and a stony moon glowed on fearsome-looking beasts.

I'm five days into a weeklong journey along the length of this former British colony wedged between Guatemala and Mexico, and it hasn't taken me long to realize that it's not just the Blue Hole that seems otherworldly. The whole country is the Yucatan on adrenaline-a natural theme park that's a little weirder and a lot wilder than anywhere else in these parts. It's a country where you can stalk gentle sharks the size of trawlers, dive South Pacific-like atolls in the Caribbean and swim deep into the Cave of the Crystal Maiden to uncover a chilling mystery more out of a gothic horror novel than a modern-day fairy tale.

Belize, I decide, watching the silver tinsel of bubbles pour out of the jaws of Xibalba and glitter to the surface like a reverse waterfall, is Where the Wild Things Are.

Stalking Giants

The evening I arrive in Placencia, a barefoot beach town in southern Belize, an Apocalypse Now sunset has ignited cloud castles in the sky-appropriate since director Francis Ford Coppola owns a Balinese-inspired resort on the edge of town.

I wander along a planked sidewalk and pass fishing shacks on stilts, hurricane shutters drawn, next to rebar quills poking out of time-share villa foundations. At the pier at the end of the road, sunburned Texan tourists in $200 Orvis fly-fishing vests unload coolers of empty Belikin beer from their boats, while local men hammer wayward nails back into fishing pangas turtled under coconut palms. Nearby, a European couple bickers over how to set up their North Face dome tent on the brown-sugar beach. The sidewalk winds past acupuncture clinics and Internet cafes, and a colorful hand-painted Creole sign admonishes potential litterbugs: "Sho Yur Luv Fo' Di Bare Foot."

Placencia's mellow vibe is lost on me two days later as I roll into the swell 25 miles offshore at the Gladden Spit Marine Reserve. I'm hot and cranky, my neck is covered with red pica-pica welts, and I'm well into my second unsuccessful day of whale shark diving.

The plankton-feeding sharks, which can grow up to 60 feet long, have been coming to Gladden Spit since the end of the last ice age. They gather to feed on the lunar spawning of the cubera snapper. "We usually see the sharks around the full moons from March until June," divemaster Francisco explains.

"Want to see what they look like?" the diver next to me asks. "We saw five the day before yesterday." Before I can say anything, he powers up his digital point-and-shoot and clicks through image after image of whale sharks feeding in the light blue surface water.

Just when I'm ready to chuck his camera overboard, Francisco hollers, "Suit up!" He's been glued to the bridge, on the lookout for fish, and he's found the cubera. Somewhere below them should be sharks.

We drop in together, descending quickly to 70 feet. The cubera are there, listless, squirming in the dim gloom. There are dog snapper, too, their large canines hanging out of their mouths. But there's something else. I don't see it at first because I'm focused too tight. All I see are spots, like hundreds of sand dollars, impossible because the bottom here is over 400 feet deep. My eyes refocus and I see a whale shark swaying through the darkness. It passes in seconds, and it's the only one we see. But it's a whale shark, and I'm smiling from ear to ear.

Back on board, the mood is grim. Only half our group saw the shark. I stretch out on the sun-warmed bench as the bow rises and we head for home. I'm back in the Placencia groove. Somewhere in the cabin I hear my friend courting disaster. "Don't worry," he says to someone. "I'll show you what they look like. I got pictures the day before yesterday."

Atolls of the Caribbean

Madonna sang about Belize's most popular dive destination in "La Isla Bonita," though the Material Girl had trouble finding words that rhymed with Ambergris Caye. She, like the locals, simply called it San Pedro after the namesake town on the island's southern tip.

Call it what you want, San Pedro is where divers come to experience the silver medalist in the Longest-Reef-in-the-World Olympics. Walking along the sandy beach fronted by open-air restaurants and sandy-floored bars, I can hear the low thunder of the Caribbean breaking over the great Mesoamerican barrier reef less than a half mile offshore.

We plow through that thunder the next morning in a small panga. I'm headed to Tackle Box Canyons. Like most of the nearly 100 dive sites fronting Ambergris, this one is only minutes from the pier on the outside slope of the barrier reef.

The surge is strong, and sea fans sway like sagebrush on a windy mesa. We find some shelter in the tongue-and-groove coral formations that dominate the offshore topography. Carlos, our divemaster, leads us through a series of swim-throughs and slot canyons at around 50 feet. In one tunnel we spook up a baby hawksbill turtle, and in another bump into a monster loggerhead in the fading spectrum of his 50-year lifespan.

San Pedro is also a jumping-off point for more distant dives in the offshore atolls. Belize has three out of only four atolls in the Caribbean. Protected by several marine sanctuaries, these coral island rings have spectacular visibility and fantastic fish life. Lighthouse Reef, nearly 50 miles out, is the farthest. There, among 75 square miles of opal shallows, is the deep sapphire eye of the Blue Hole.

I leave for Lighthouse Reef just before sunrise. It's a long, bumpy ride; two hours of smashing through 10-foot seas and watching wave-slapped divers tip their heads over the stern in seasick prayer.

The price is worth it. The heavy seas have kept all but one other boat from the 400-foot-deep crater. The Blue Hole is really a collapsed cave formed 15,000 years ago when the reef was dry. Rainwater melted through the karstic limestone and ate away a massive cave system. At some point, part of the ceiling collapsed, creating the hole.

It's our first dive of the day, and with just eight minutes at our depth of 130 feet, it will be our shortest. We gather in the shallow 82-degree water rimming the hole before descending over a sandy bank. At 50 feet, the slope falls away into the dark abyss. I feel a chill and look at the temperature reading on my computer; it's dropped six degrees.

I've dived the Blue Hole before, and I always wonder if it's not just the hype from Jacques Cousteau's famous 1970s expeditions that draws us all out here. There's little coral growing inside the hole, only cornflake algae, and few fish. It's deep and gloomy. But then I hit 130 feet and see the stalactites and dripstone pillows and cave entrances, and I know exactly why I came.

The Blue Hole finished, anxiety in our group vanishes; the deepest, darkest dive is done. Seven miles south at Half Moon Caye we indulge in a sunny surface interval on a white crescent beach amid slender palms. From a nearby bird-viewing platform, I'm treated to the noisy revelry of more than 2,000 breeding pairs of red-footed boobies, one of nearly 100 bird species counted on the island.

Our last dive is Aquarium, off the northwest corner of nearby Long Caye. Karen Healey, director of Reef Conservation International, had already warned me about Aquarium when I met with her on the mainland. "In most of Belize, you're happy if you see a dozen snapper," she said. "Dive the Aquarium and you'll see 300." And the grouper, she sighed. "They're almost obnoxious there. They come right up to you."

She was right. After sweeping over a sandy field of garden eels, we peel out over the wall into swarms of yellowtail snapper and Creole wrasse; a dozen beefy grouper trail along after us. In the final minutes of our safety stop, we're entertained by a spotted eagle ray flying lazy patterns beneath our fin tips.

The Cave of the Crystal Maiden

Ian Anderson, owner of Caves Branch Adventure Company and Jungle Lodge, leans back in his chair and lets the blue smoke from his cigarette roll into the night. A Canadian with a square jaw and Robert Redford hair, Ian arrived here sight unseen in 1993 after watching a show about Belize on the Travel Channel. We're sitting in the outdoor dining room of his lodge an hour west of Belize City, talking about wild places and caves.

"The Maya believed caves were the entrances to Xibalba," he says, "literally Ôthe place of fear.'" It's that taboo that has drawn adventurers to them. "These caves are hundreds of thousands of years in the making. When you go in, you hear the sound of time passing, that drip-drip-drip that has been going on for an eternity. There are limestone crystals sparkling on the walls like diamonds. It's mind-boggling."

With a few days left before my flight home, I've decided to explore these places of fear, and along the way learn a bit about Maya culture. They ruled a vast arrowhead of jungle that included the Yucatan, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and parts of El Salvador from 1,000 years ago until the 17th century. And then they vanished. There are many theories as to why they disappeared: sectarian warfare, famine, disease, environmental destruction. But what exactly happened to the Maya remains a mystery.

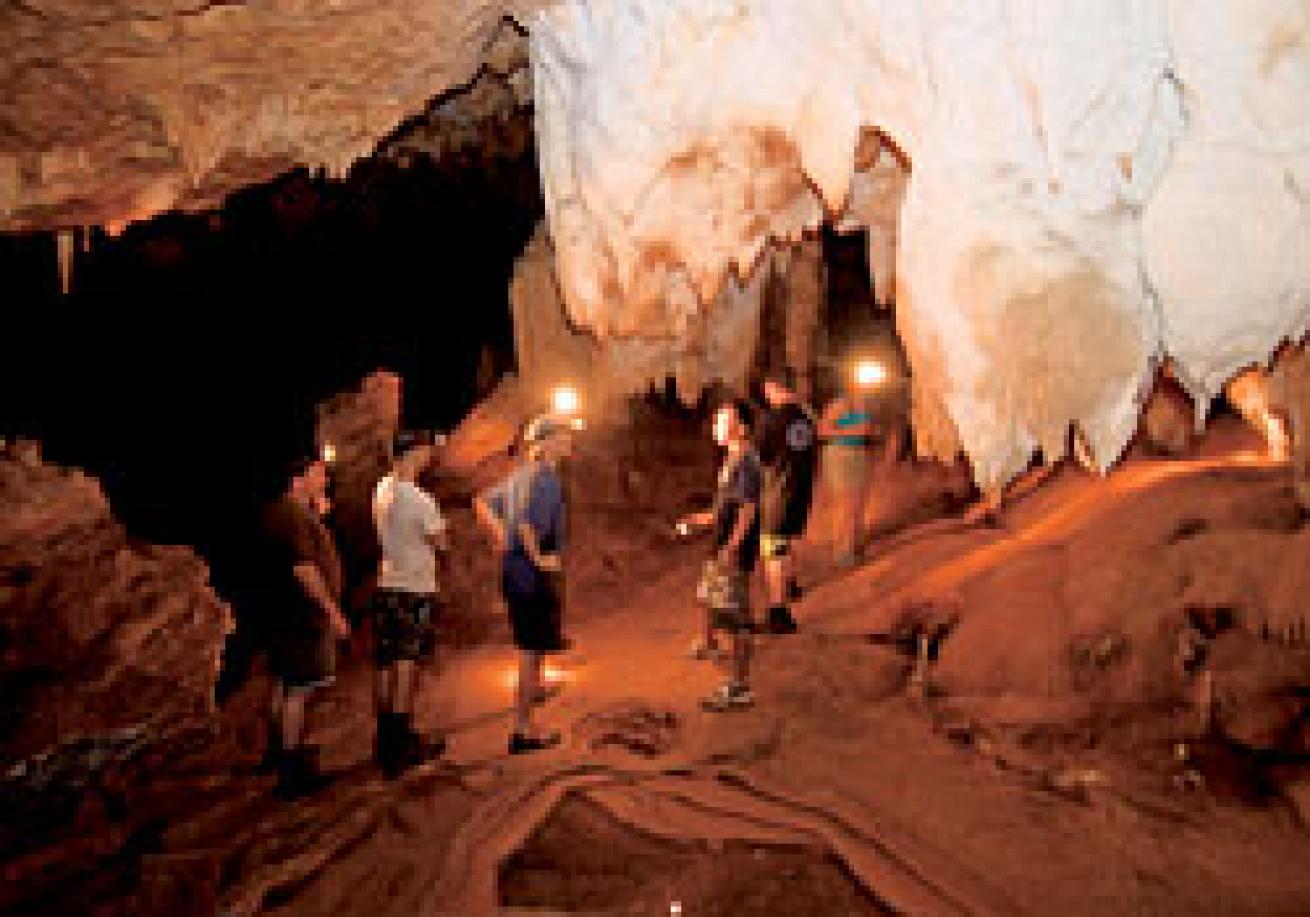

I have a peek at that mystery inside the Maya Footprint Cave, one of 63 caves that Ian has discovered on his property. Along with three brothers from Florida, I alternately tube and hike deep inside the underworld. It isn't just the stone formations we are anxious to see. Ian had told me the caves played an important role for the Maya, especially in the declining years of the empire. Inside the Footprint Cave, our guide points out Maya pots that once held offerings of corn and chili peppers and lets us hold obsidian blades used for bloodletting ceremonies.

I ask Ian about the artifacts. "Unlike the temples in the big Maya cities where the priests would perform public ceremonies," he says, "what they did in Xibalba was secretive." These secrets included not just offerings of food and incense, he says, but sometimes children. I heard about one such cave an hour west-the mysterious Actun Tunichil Muknal, Cave of the Stone Sepulcher. I head there the next day with Emilio Awe, owner of PACZ Tours, and naturalist Rudy Neal. It's an hour hike through the jungles of the Roaring Creek Valley; along the way Rudy points out the parallel scars raked on a young tree by a jaguar marking his territory and shows me a fat mother tarantula guarding an egg case.

I feel the cave before I see it, the cool, damp whisper of 72-degree air bleeding through the triple-digit heat. While I pack my cameras into a dry bag at the hourglass entrance-a clear river flows out of the entrance, so we will have to swim inside-I spot Rudy standing with his eyes closed at the entrance. "Saying a prayer?" I ask. "Asking permission," he says. "From the gods who live here."

We work our way past a rock maze near the entrance, squeezing through narrow cracks no wider than our shoulders and fording oil-black pools. Four hundred feet beneath the rainforest above and a half mile inside Xibalba, we finally crawl through the last gap. We are inside a chamber the size of a Broadway theater.

The orange cones of our headlamps illuminate a magical world of candle-wax stalactites and travertine dams. Emilio tells me to take off my shoes. "Step where I step, walk where I walk," he cautions. I see why. The ochre clay floor is littered with thousands of ceramic pottery shards, some as big as salad bowls.

There are also other relics, more disturbing ones. We pause at a human skull, crystallized by a buildup of calcium carbonate left behind by hundreds of years of standing water. "There are 14 bodies in here," Emilio says, "all of them sacrifices. Probably to Chac, the rain god."

In a black catacomb above the main chamber we find the Crystal Maiden, a woman in her 20s. She is sprawled on her back, head slightly raised, jaws open in a silent cry. "Our best guess is that she was sacrificed to Ixchel, the goddess of fertility," Emilio whispers. We sit for a moment beside her bones, so crusted in calcium carbonate that they sparkle like broken glass. The cave continues on for another four miles, but we've reached the end of our tour. We've seen its haunted soul.

On the quiet ride back down through the valley, I wonder what happened to the Maya. Where did they go? There was once a Maya city in this valley, Cahal Witz Na. But now there's just broken farmland, sweet-smelling orange groves and thick jungle.

We stop at a small farmhouse, where a splash of yellow corn lies drying. A young boy swings in a woven hammock and teases a sallow-eyed dog.

I ask if I can take a picture of the corn, and he says sure. When I show him the digital image, he calls his father outside. He's a small, thin man with coffee skin and fine features. A parrot perched on his bare shoulder tries to preen his ear. "Can I take your photo?" I ask. "Sure," he says, "but make sure you get the parrot." I take one, and as I do I realize I've just answered my own question. In the land where the wild things are, the Maya have never left.

Dive In

Water Conditions: Mid-70s in winter and low to mid-80s in summer. Wear at least a Lycra skin to ward off coral abrasions. Off Ambergris Caye, water clarity is variable, though generally decent. Visibility off the atolls is rarely bad, but it's best from April to June.

Weather: Tropical, which means pretty warm year-round. The coast, cayes and atolls enjoy a brisk prevailing wind from the Caribbean, which moderates the heat.

Documents: Passport and proof of return is required.

Money Matters: The Belize dollar (BZ$) trades at BZ$2 to US$1. Credit cards and traveler's checks are accepted throughout the country. There is a $35 departure tax, payable in U.S. dollars only.

Time: The same as Central Standard in the U.S. Daylight saving time is not observed.

Electricity: The same as in the U.S.-110 volts, 60 cycles-and the country uses the North American-style two-pin plug.

Tourism: Visit the web site of the Belize Tourism Board at www.travelbelize.org.

Dive Operators: For detailed information on Belize dive operators, comprehensive travel guides, special dive deals and recent trip reports submitted by users, go to TripFinder on our web site at http://dive.scubadiving.com/tripfinder.