Russian Roulette: World War II Wrecks in the Black Sea

The Heavily loaded SUV thunders along the road — at certain points, photographer René Lipmann can barely avoid the potholes, but our double tanks in the back don’t seem affected. We drive up the steep hills with smiles on our faces, while a camper has to call it quits because it cannot make the ascent. Leaving ancient forests and the rugged Carpathian Mountains behind us, we arrive at the Romanian coastal town of Constanta, where a large boardwalk along the Black Sea leads us to Aquarius, a dive center that belongs to Dutchman Harry Bakker. His dive school is one of the few in this city, although the multitude of wrecks here offers divers much to choose from. We are here for the recently discovered Moskva and the Russian sub SC213. The Black Sea is far wilder than our own North Sea: The wind can suddenly change, and increases in intensity every hour — there’s a reason that the Black Sea was known to the ancient Greeks as Pontos Axeinos, or the “Inhospitable Sea.”

We don’t embark until the second day, in Bakker’s 200-horsepower RIB. At times he looks at the sky worriedly, although he tries to hide it. I already have half of my drysuit on — a good thing, with all the splashing. The water moves in a ghostly manner; the direction of the waves looks as if a large, submerged monster is following our movements.

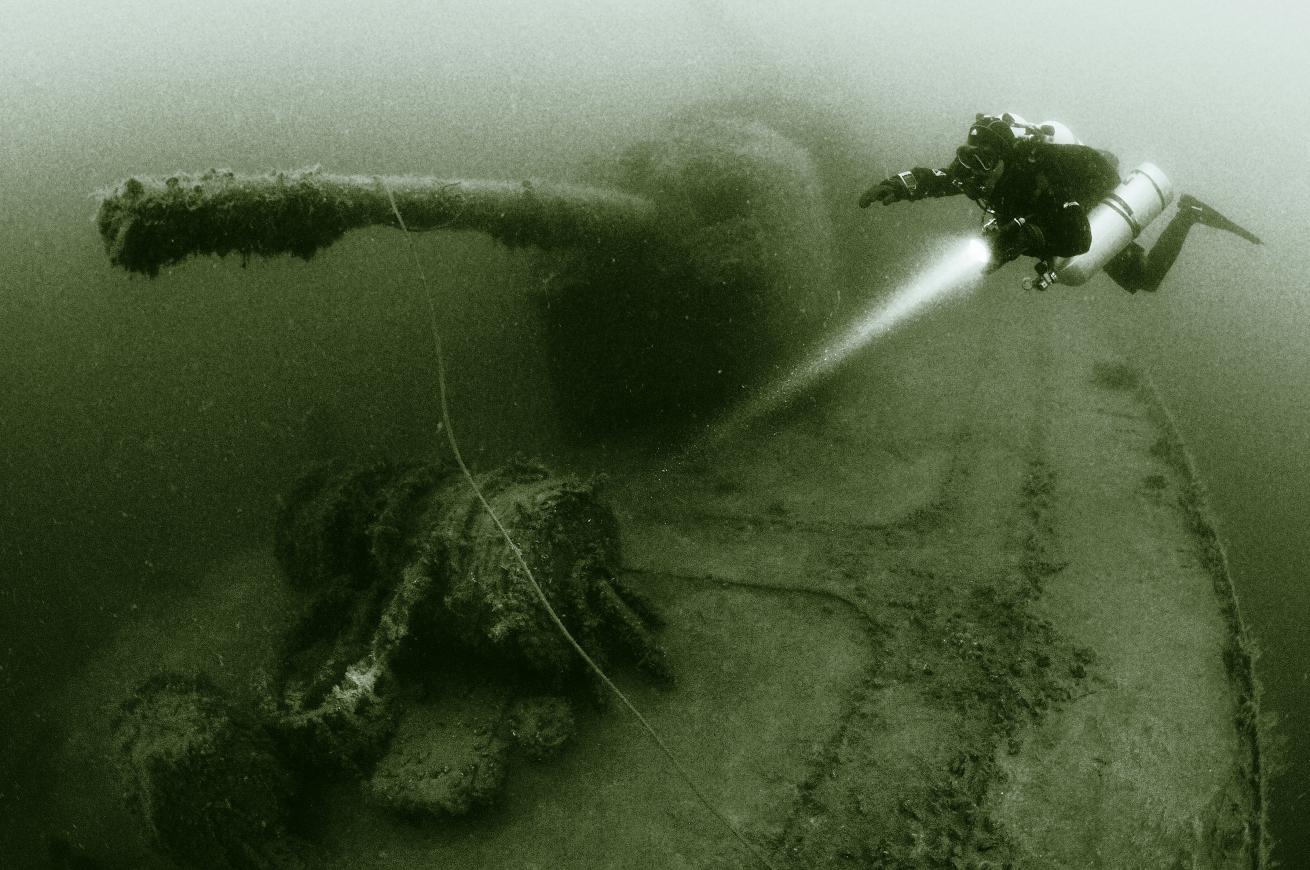

Within a half-hour we reach the site of Moskva. The strange swell is making me nauseated, so I quickly jump in to cool of, but the 80-degree water doesn’t really do the trick. After an uneventful descent, I’m pleasantly surprised to find much more light than I expected at 90 feet. I am a bit shocked, however, by the sudden drop in temperature, from 80 degrees to 45. Then, suddenly, a piece of the wreck emerges. Exactly on the anchor-line position, the ship is broken in two — we descend into the remains of an enormous explosion. It’s difficult to find our bearings; we can see only a few yards ahead of us. I begin to recognize the contours of a ship — touchdown! We swim across a compass, and I recognize four torpedo tubes, and behind them an installation of antiaircraft guns.

In 2011, the wreckage of Moskva was discovered by a team of Russian Global Underwater Explorers (also known as GUE). Well, half of it anyway — the bow section is still missing, although we have our suspicions as to where it can be found. I’m over- whelmed to be here at all; fewer than 20 divers have visited the wreck of this 418-foot destroyer. A few yards ahead I see the enormous barrel of a 130 mm canon that once fired on Constanta. I quietly swim past and look behind the armored shield; in front of this artillery, a few machine guns with their machine depots can still be found. It’s striking that there’s so little growth on the wreck; as a result, many more details emerge.

FRIENDLY FIRE

On the quarterdeck between two cannons is a semicircular construction, a type of cover for crew members operating the lower cannon. The trapdoors are open; inside my light illuminates where the crew used to sit — I can only imagine the deafening noise. Back across the torpedoes, I swim past a large chimney that has fallen across the structure. Nearby, a machine gun still on its supporting base has shifted a bit.

Unfortunately we soon reach our minimum gas levels for ascent and have to go up. Despite the poor visibility, we rapidly find the anchor line and commence a good half-hour of decompression in lovely warm water. Tiny fish surround us, but I hardly notice; my thoughts are with the wreck and the dive. With mixed feelings, we make the last stops and climb back on board the RIB. With a fierce wind in my face, I think about a commemoration that took place here not long ago. On June 26, 2011 — exactly 70 years after the 1941 sinking of the Moskva — the Russian government organized a large memorial service. A Russian marine ship placed wreaths on the water, and fireworks thundered overhead, a sign of respect for those who lost their lives aboard.

It’s strange, however, to think that such a large destroyer could hit a sea mine, break in two, and sink so quickly. There are multiple theories about Moskva’s demise, one of which the Russians utterly reject: Eyewitnesses that day say they saw multiple torpedo attacks on Moskva and nearby Kharkov. The question is, from where could such an attack have originated? The only submarine known to be in the neighborhood was the SC206. That makes it possible that Moskva was sunk by friendly free from its own Russian SC206. Since then, the SC206 seems to literally and figuratively have disappeared from history. It is public knowledge that the submarine sank during the war, but the coordinates were very roughly estimated. Not only has the SC206 yet to be located, but evidence has been found that the Russians have purposely hidden its location.

COVER-UP

To clear our heads, we walk along the boardwalk in front of the diving school. A bit farther on, we come to the casino. It’s a beautiful old building, dating from 1910, that stands proudly on the rocks along the sea. Almost every day, newlywed couples come here for wedding photos. To our consternation, up close the building is revealed to be desolate and abandoned, with no money and no motivation to restore it. This is true for all of Romania, where the Communist legacy is visible everywhere. After the execution of party leader Nicolae Ceausescu on Christmas Day in 1989, the country was in economic shambles; only in the past 10 years has prosperity, and tourism, increased. Bakker asks if we can handle another story, and we nod with caution.

He tells us that in 2008, he received coordinates from a sport diver who had discovered a strange-looking object in the Black Sea. Bakker went to explore, and at 90 feet he found a submarine. Because it was covered in nets, it was difficult to identify; eventually he managed to remove a convex-shaped object from the wreckage for identification. It turned out to be a gyrocompass that could only have come from the Russian sub SC213 *(SC stands for *shchuka, or pike, in Russian). Bakker informed Russian authorities in Romania of the discovery — the entire crew of 43 had died when the SC213 hit a mine on Oct. 14, 1942 — but he never received a response from the Russian authorities.

The SC213’s involvement in one of the greatest maritime disasters of WWII could hold a clue. The Bulgarian ship Struma left Constanta in December 1941 with 769 Jewish refugees on board, trying to reach the safety of the British Mandate in Palestine. The ship had engine trouble and arrived instead in Istanbul. Neither the Turks nor the Brits really wanted to take in or help the refugees. After Struma had been two months in the harbor, the Turkish government cut its anchor ropes, and the ship was set adrift in the Black Sea. The day after, on Feb. 24, 1942, Struma was torpedoed by the SC213. Of 769 people on board, only a single 19-year-old survived.

THE PIKE

The 192-foot SC213 is the wreck we are diving today, lying at a maximum depth of about 100 feet. Its tail with two propellers lies partly in the sand, but the rest of the submarine is completely clear. At its tip the sandy bottom has been swept away a bit, and it has almost come away from the seafloor. Unfortunately, the boat has been covered in nets from top to bottom, and we don’t have a clear view of what is beneath them. Two periscopes stick out; the glass eye of an antiaircraft periscope is still transparent and glistening. I find myself wishing that the periscope would look in instead of out, so I could peer into the submarine. Right behind the first one is a second, smaller periscope: the attack periscope. It’s unclear whether any part of the interior is still dry — the only certainty is that the entire crew is still inside. The thought gives me the creeps.

Later, after analyzing photos, we discover that the amount of netting on the boat has seriously increased since the previous winter. Then, the bow was completely bare; now it’s entirely covered. Because the nets present a danger to divers and marine life — but also because we would like to photograph the bow without the nets — when we return, we spend an entire dive removing the nets. After about 45 minutes, the nets in the front are gone, restoring a beautiful view of the enormous opening where torpedoes left the submarine. From this porthole, the torpedo made its way to Struma, which exploded.

Our last dive to the SC213 is pure bliss — after an hour on the surface, all the dust has settled, and only now do I see the result of our hard work. It seems as if the Pike has come alive again.

CONNECTING THE DOTS

The wrecks we visited seemingly did not have a connection, but they are most likely inextricably linked. Russian archives contain images that show the SC213, with the gyrocompass that Bakker retrieved, in a place that matched only that sub. The fact that no one was seeking the SC213 is perhaps logical — it was responsible for the murder of almost 800 Jewish refugees — but why the silence on the whereabouts of SC206? The most logical explanation for hiding that sub — and for the enormous explosion on the Moskva — are probably one and the same: Moskva was torpedoed by its own submarine, the SC206.

DIVE CONDITIONS

The top layer of the Black Sea can reach nearly 80 degrees, but deeper down it is remarkably cold. Visibility ranges from 15 to 30 feet, and though there can be a surface current, at depth there is no heavy current. Therefore the sea is very suitable for shallow dives; sites are accessible from the shore or from a small boat like an RIB.

The house reef belonging to the Aquarius Dive Center offers shelter to a host of seahorses. During our visit, we were fortunate to spot dolphins on multiple occasions.

DIVE CENTER

Aquarius Dive Center is owned by Harry Bakker and his wife, Doina Geana. Their team organizes a variety of PADI and IANTD training sessions, and also puts together wreck-diving expeditions.

There are wreck dives available for every level of diver. The transport ships Arkadia and Mitera Zafira and bulk carrier You Xiu are in depths that are accessible to recreational divers.

Aquarius offers nitrox and all deco gases up to 100 percent. Trimix is available on demand. A full range of gear is available to rent. (aquarius-diving.ro)

TRANSPORTATION

It is possible to fly to Constanta, but flying into Bucharest is a better option. From the capital, it is a solid two-hour drive to Constanta.

Rene LipmannOne Black Sea wreck is celebrated, while the sister submarine that may have torpedoed it is left to oblivion. The true story, preserved on the seafloor, will make your hair stand on end.

The Heavily loaded SUV thunders along the road — at certain points, photographer René Lipmann can barely avoid the potholes, but our double tanks in the back don’t seem affected. We drive up the steep hills with smiles on our faces, while a camper has to call it quits because it cannot make the ascent. Leaving ancient forests and the rugged Carpathian Mountains behind us, we arrive at the Romanian coastal town of Constanta, where a large boardwalk along the Black Sea leads us to Aquarius, a dive center that belongs to Dutchman Harry Bakker. His dive school is one of the few in this city, although the multitude of wrecks here offers divers much to choose from. We are here for the recently discovered Moskva and the Russian sub SC213. The Black Sea is far wilder than our own North Sea: The wind can suddenly change, and increases in intensity every hour — there’s a reason that the Black Sea was known to the ancient Greeks as Pontos Axeinos, or the “Inhospitable Sea.”

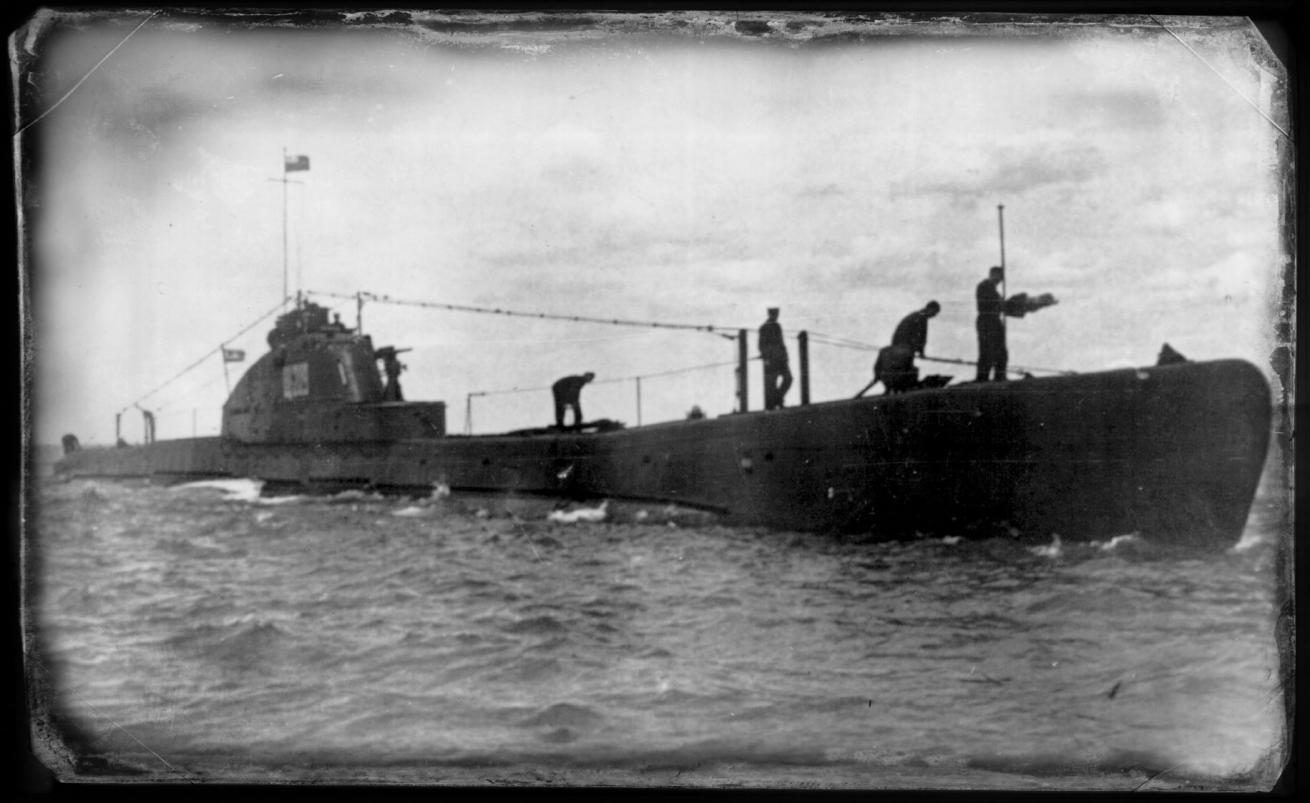

Rene LipmannA photo of the SC213 submarine before it sank.

We don’t embark until the second day, in Bakker’s 200-horsepower RIB. At times he looks at the sky worriedly, although he tries to hide it. I already have half of my drysuit on — a good thing, with all the splashing. The water moves in a ghostly manner; the direction of the waves looks as if a large, submerged monster is following our movements.

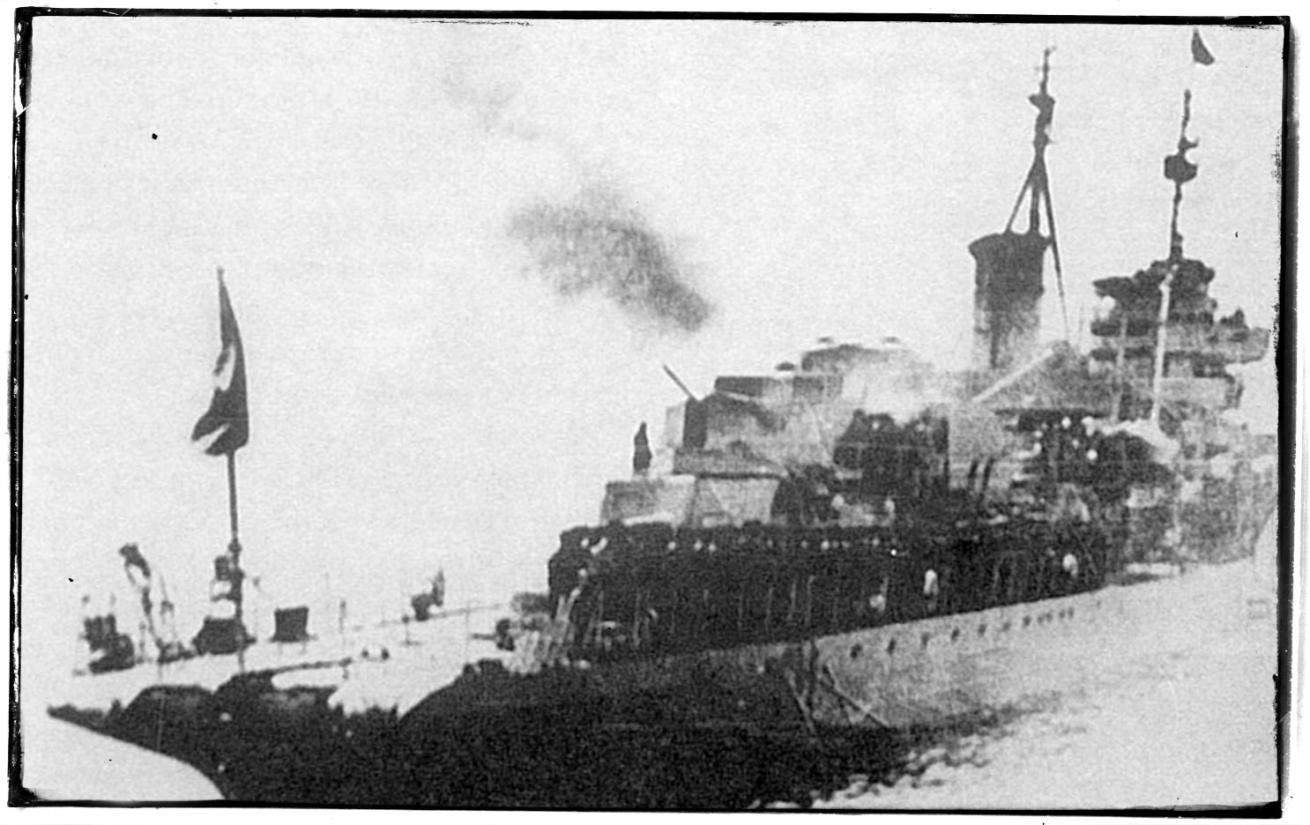

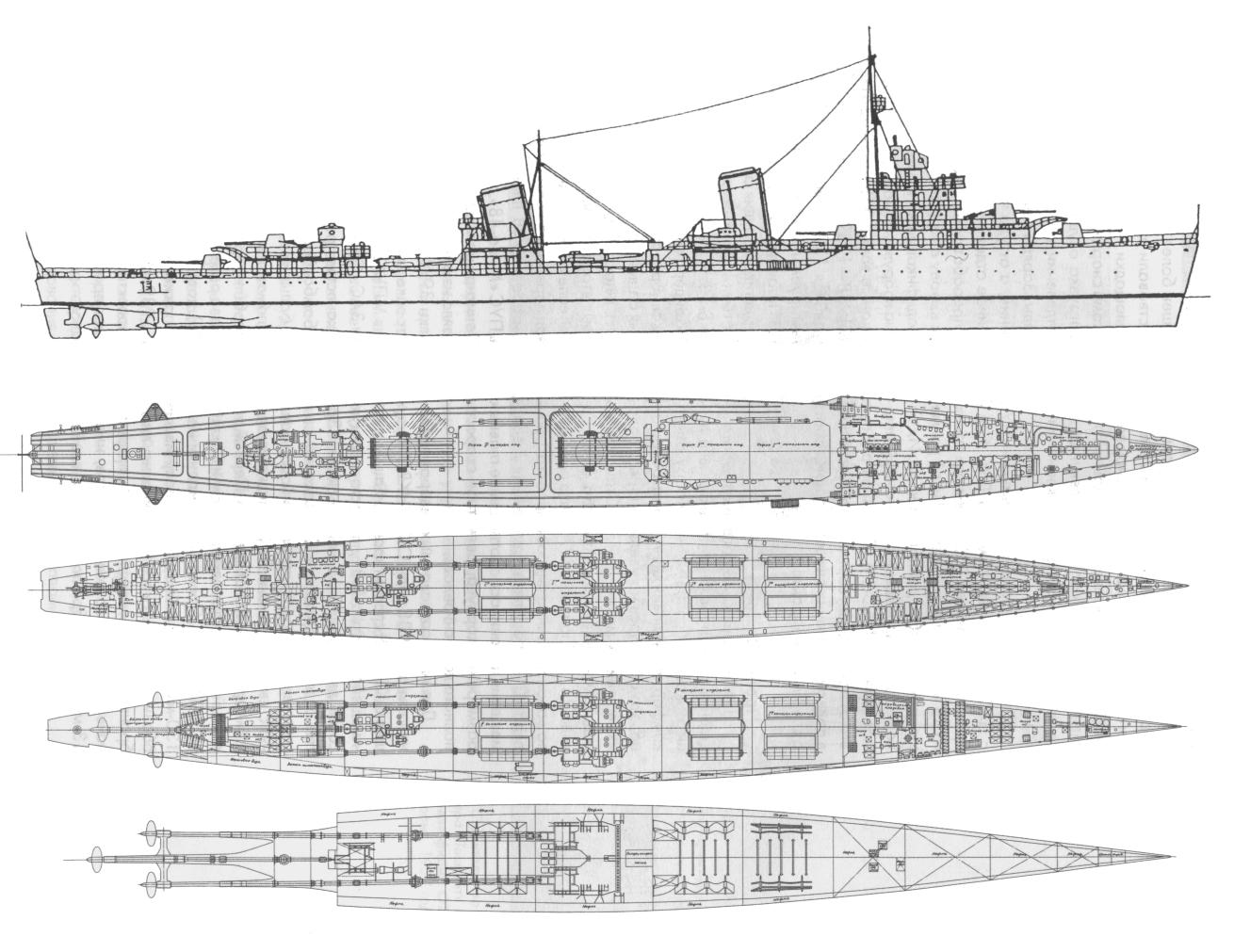

Rene LipmannThe Russian submarine SC213 was responsible for one of the greatest maritime disasters of World War II, on Feb. 24, 1942.

Within a half-hour we reach the site of Moskva. The strange swell is making me nauseated, so I quickly jump in to cool of, but the 80-degree water doesn’t really do the trick. After an uneventful descent, I’m pleasantly surprised to find much more light than I expected at 90 feet. I am a bit shocked, however, by the sudden drop in temperature, from 80 degrees to 45. Then, suddenly, a piece of the wreck emerges. Exactly on the anchor-line position, the ship is broken in two — we descend into the remains of an enormous explosion. It’s difficult to find our bearings; we can see only a few yards ahead of us. I begin to recognize the contours of a ship — touchdown! We swim across a compass, and I recognize four torpedo tubes, and behind them an installation of antiaircraft guns.

Rene LipmannA diver works to remove nets from a Black Sea wreck.

In 2011, the wreckage of Moskva was discovered by a team of Russian Global Underwater Explorers (also known as GUE). Well, half of it anyway — the bow section is still missing, although we have our suspicions as to where it can be found. I’m over- whelmed to be here at all; fewer than 20 divers have visited the wreck of this 418-foot destroyer. A few yards ahead I see the enormous barrel of a 130 mm canon that once fired on Constanta. I quietly swim past and look behind the armored shield; in front of this artillery, a few machine guns with their machine depots can still be found. It’s striking that there’s so little growth on the wreck; as a result, many more details emerge.

Rene LipmannMoskva may have been sunk by friendly fire in 1941.

FRIENDLY FIRE

On the quarterdeck between two cannons is a semicircular construction, a type of cover for crew members operating the lower cannon. The trapdoors are open; inside my light illuminates where the crew used to sit — I can only imagine the deafening noise. Back across the torpedoes, I swim past a large chimney that has fallen across the structure. Nearby, a machine gun still on its supporting base has shifted a bit.

Unfortunately we soon reach our minimum gas levels for ascent and have to go up. Despite the poor visibility, we rapidly find the anchor line and commence a good half-hour of decompression in lovely warm water. Tiny fish surround us, but I hardly notice; my thoughts are with the wreck and the dive. With mixed feelings, we make the last stops and climb back on board the RIB. With a fierce wind in my face, I think about a commemoration that took place here not long ago. On June 26, 2011 — exactly 70 years after the 1941 sinking of the Moskva — the Russian government organized a large memorial service. A Russian marine ship placed wreaths on the water, and fireworks thundered overhead, a sign of respect for those who lost their lives aboard.

It’s strange, however, to think that such a large destroyer could hit a sea mine, break in two, and sink so quickly. There are multiple theories about Moskva’s demise, one of which the Russians utterly reject: Eyewitnesses that day say they saw multiple torpedo attacks on Moskva and nearby Kharkov. The question is, from where could such an attack have originated? The only submarine known to be in the neighborhood was the SC206. That makes it possible that Moskva was sunk by friendly free from its own Russian SC206. Since then, the SC206 seems to literally and figuratively have disappeared from history. It is public knowledge that the submarine sank during the war, but the coordinates were very roughly estimated. Not only has the SC206 yet to be located, but evidence has been found that the Russians have purposely hidden its location.

Rene LipmannTHE STORY BEHIND THE SHIP

THE STORY BEHIND THE SHIP

Germany and the Axis Powers — which included Romania — officially declared war on Russia on June 22, 1941. Four days later, a Russian fleet arrived to destroy as many oil wells in Constanta harbor as possible. The small Russian fleet consisted of two destroyer leaders — Kharkov and Moskva — a cruiser and two C-class destroyers. At 5 a.m., heavy cannon shots were heard across the Black Sea. After only the second round, the main target had been hit and the oil reserve went up in flames. Two Romanian destroyers attacked Moskva and Kharkov but completely missed their targets. In the second round, they missed from only dozens of yards. Moskva and Kharkov retreated, and threw up a smoke curtain. But the wind dispelled the curtain, and they were under fire again. Moskva got the order to increase its speed. Almost immediately afterward, an enormous explosion was heard. A white bolt of lightning shot 30 yards in the air. The destroyer leader broke in two and started to sink. Kharkov tried to save the crew but to no avail. At 05:28 Kharkov was ordered to retreat and to abandon its battle comrades. Of 344 crew members, 62 sailors and 7 officers were picked up by motorboats and Romanian water planes throughout the night; the rest had drowned.

Scuba DivingSign up for the Scuba Diving eNewsletter

Sign up for the Scuba Diving eNewsletter

Scuba Diving is the complete source for the best in diving information. Get the latest in-depth information on destinations both near and far, reviews of must-have gear, breathtaking underwater photos, news on the latest technology, updates on environmental issues and more — all delivered right to your inbox!

COVER-UP

To clear our heads, we walk along the boardwalk in front of the diving school. A bit farther on, we come to the casino. It’s a beautiful old building, dating from 1910, that stands proudly on the rocks along the sea. Almost every day, newlywed couples come here for wedding photos. To our consternation, up close the building is revealed to be desolate and abandoned, with no money and no motivation to restore it. This is true for all of Romania, where the Communist legacy is visible everywhere. After the execution of party leader Nicolae Ceausescu on Christmas Day in 1989, the country was in economic shambles; only in the past 10 years has prosperity, and tourism, increased. Bakker asks if we can handle another story, and we nod with caution.

He tells us that in 2008, he received coordinates from a sport diver who had discovered a strange-looking object in the Black Sea. Bakker went to explore, and at 90 feet he found a submarine. Because it was covered in nets, it was difficult to identify; eventually he managed to remove a convex-shaped object from the wreckage for identification. It turned out to be a gyrocompass that could only have come from the Russian sub SC213 *(SC stands for *shchuka, or pike, in Russian). Bakker informed Russian authorities in Romania of the discovery — the entire crew of 43 had died when the SC213 hit a mine on Oct. 14, 1942 — but he never received a response from the Russian authorities.

The SC213’s involvement in one of the greatest maritime disasters of WWII could hold a clue. The Bulgarian ship Struma left Constanta in December 1941 with 769 Jewish refugees on board, trying to reach the safety of the British Mandate in Palestine. The ship had engine trouble and arrived instead in Istanbul. Neither the Turks nor the Brits really wanted to take in or help the refugees. After Struma had been two months in the harbor, the Turkish government cut its anchor ropes, and the ship was set adrift in the Black Sea. The day after, on Feb. 24, 1942, Struma was torpedoed by the SC213. Of 769 people on board, only a single 19-year-old survived.

THE PIKE

The 192-foot SC213 is the wreck we are diving today, lying at a maximum depth of about 100 feet. Its tail with two propellers lies partly in the sand, but the rest of the submarine is completely clear. At its tip the sandy bottom has been swept away a bit, and it has almost come away from the seafloor. Unfortunately, the boat has been covered in nets from top to bottom, and we don’t have a clear view of what is beneath them. Two periscopes stick out; the glass eye of an antiaircraft periscope is still transparent and glistening. I find myself wishing that the periscope would look in instead of out, so I could peer into the submarine. Right behind the first one is a second, smaller periscope: the attack periscope. It’s unclear whether any part of the interior is still dry — the only certainty is that the entire crew is still inside. The thought gives me the creeps.

Later, after analyzing photos, we discover that the amount of netting on the boat has seriously increased since the previous winter. Then, the bow was completely bare; now it’s entirely covered. Because the nets present a danger to divers and marine life — but also because we would like to photograph the bow without the nets — when we return, we spend an entire dive removing the nets. After about 45 minutes, the nets in the front are gone, restoring a beautiful view of the enormous opening where torpedoes left the submarine. From this porthole, the torpedo made its way to Struma, which exploded.

Our last dive to the SC213 is pure bliss — after an hour on the surface, all the dust has settled, and only now do I see the result of our hard work. It seems as if the Pike has come alive again.

CONNECTING THE DOTS

The wrecks we visited seemingly did not have a connection, but they are most likely inextricably linked. Russian archives contain images that show the SC213, with the gyrocompass that Bakker retrieved, in a place that matched only that sub. The fact that no one was seeking the SC213 is perhaps logical — it was responsible for the murder of almost 800 Jewish refugees — but why the silence on the whereabouts of SC206? The most logical explanation for hiding that sub — and for the enormous explosion on the Moskva — are probably one and the same: Moskva was torpedoed by its own submarine, the SC206.

DIVE CONDITIONS

The top layer of the Black Sea can reach nearly 80 degrees, but deeper down it is remarkably cold. Visibility ranges from 15 to 30 feet, and though there can be a surface current, at depth there is no heavy current. Therefore the sea is very suitable for shallow dives; sites are accessible from the shore or from a small boat like an RIB.

The house reef belonging to the Aquarius Dive Center offers shelter to a host of seahorses. During our visit, we were fortunate to spot dolphins on multiple occasions.

DIVE CENTER

Aquarius Dive Center is owned by Harry Bakker and his wife, Doina Geana. Their team organizes a variety of PADI and IANTD training sessions, and also puts together wreck-diving expeditions.

There are wreck dives available for every level of diver. The transport ships Arkadia and Mitera Zafira and bulk carrier You Xiu are in depths that are accessible to recreational divers.

Aquarius offers nitrox and all deco gases up to 100 percent. Trimix is available on demand. A full range of gear is available to rent. (aquarius-diving.ro)

TRANSPORTATION

It is possible to fly to Constanta, but flying into Bucharest is a better option. From the capital, it is a solid two-hour drive to Constanta.