Drysuit Diving Guide: What You Should Know About Diving Dry

WHAT DO I NEED TO KNOW ABOUT DRYSUITS?

Courtesy DAN/Ashley MinkusProper training can open up a world of possibilities for drysuit divers.

Drysuits are standard fare for divers who spend a lot of time underwater — and those who live in colder regions. The suits are inflatable, watertight shells that seal around a diver’s body to protect him or her from the elements. While they are generally easy to dive with a little practice, they can be intimidating to new divers. Drysuits are more expensive than wetsuits, come in dozens of different designs, and require a unique set of skills to dive. Here’s what you need to know before diving dry.

HOW DOES A SCUBA DRYSUIT WORK?

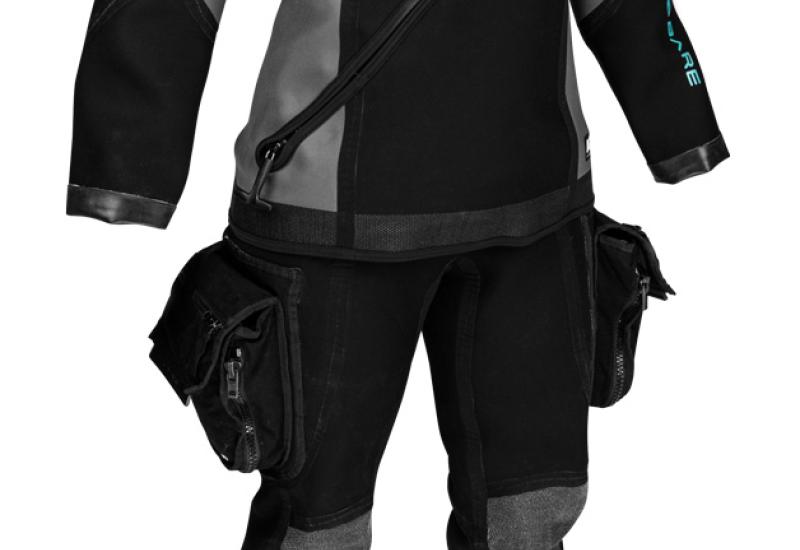

A: A drysuit is a waterproof suit that creates a dry envelope around a diver’s body to protect him or her from getting wet. Air transfers heat from the body as much as 25 times slower than water. This, plus the combination of the drysuit and insulating undergarments, allows a diver to stay warm for much longer than when wearing a wetsuit. A drysuit uses flexible rubber, neoprene or silicone to create a watertight seal around the diver’s neck and wrists, and a special waterproof zipper across the back or chest allows the diver to enter the suit easily and seal it around his or her torso. A valve mounted on the chest of the suit and a vent mounted on the shoulder allow divers to add or purge air from the suit to offset the effects of pressure and maintain neutral buoyancy during a dive.

SEE SCUBALAB'S LATEST DRYSUIT REVIEW

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF DRYSUIT DIVING?

A: One of the primary risks of diving in a drysuit is loss of buoyancy control. The air in your drysuit will expand as you ascend, and if the suit is not properly vented or an inflator valve sticks open, you might experience an uncontrolled ascent. Conversely, if you do not add enough air to the suit on descent, it could tighten around you and cause rashes, chafing and bruising.

If neck or wrist seals are too tight, they can restrict blood flow and cause lightheadedness, a carotid sinus reflex, difficulty breathing, and numbness and loss of dexterity in the hands. With proper maintenance and management of the air in your drysuit, these incidents are entirely avoidable, but it is wise to seek proper training before diving dry.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON DRYSUITS AND SAFE DIVING PRACTICES, VISIT DAN.ORG.