John Halas Earns Sea Hero Honor for Pioneering Global Buoy Use

YEAR DIVE CERTIFIED: 1964

AGE WHEN CERTIFIED: 20

DIVE CERTIFICATION LEVEL: NAUI Advanced, YMCA Instructor, SSI Platinum Pro, IANTD Rebreather, Scientist In The Sea (Florida State University graduate certification)

WORDS TO LIVE BY: “Just when you think things are bad, think again; they might have been worse.”

John Halas’ Sea Hero credentials are so numerous a paragraph can barely contain them—Vietnam vet who returned to that country five times after the war to help it create a robust system of marine-protected areas; first full-time employee for what would become the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary; 32-year veteran of that sanctuary as a manager and marine biologist. But it’s something very particular that he did in 1981, within a year of starting with the sanctuary, for which the name Halas will be remembered in the underwater world. Observing the damage done to coral reefs day in and day out by boat anchors, he created a system for mooring buoys that was easy and cost-effective to install and use. Today, nearly 40 years and thousands of mooring buoys later, untold acres of coral reef in more than 38 countries from the Cayman Islands to Malaysia have been protected by this simple device that helped to create a culture where mooring buoys are industry-standard, accessible to all, and preferred practice for responsible boaters everywhere.

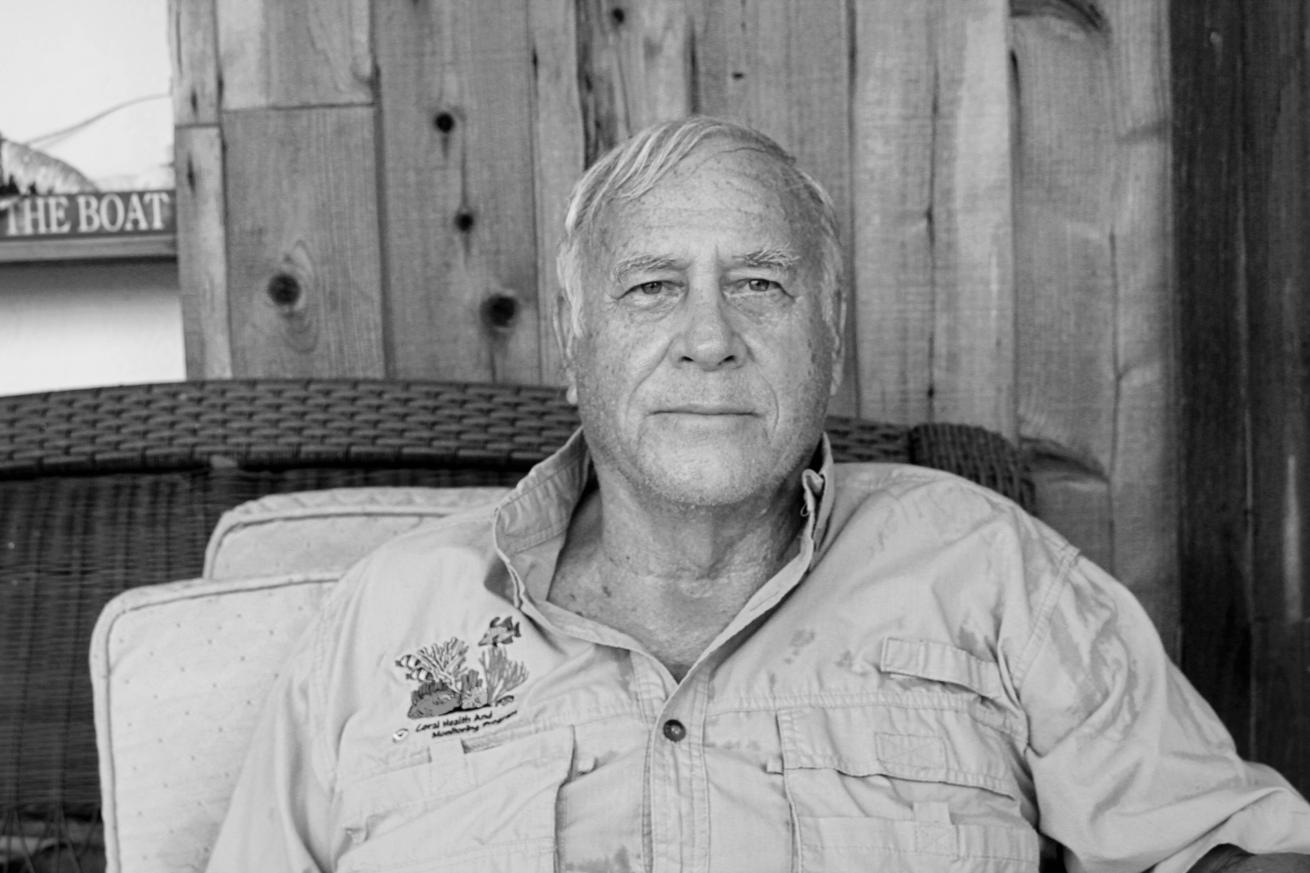

Courtesy Judy HalasJohn Halas

Q: You came up with the idea for a mooring buoy system when you were still quite new at what would become the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary—what persuaded you that this was a problem that needed to be solved?

A: I have lived and dived in the Florida Keys since the fall of 1969. During my time in the sport diving industry in the 1970s, I witnessed firsthand the increasing coral damage from boat anchors that was occurring on popular dive sites as boating and dive shop operations were on the rise in the Florida Keys. I had discussions about this with other dive boat operators at the end of dive days over a beer. We agreed that coral damage was a critical issue and that if funding was available and an adequate number of mooring buoys could somehow be installed on several of the popular dive sites with fragile corals, without causing collateral coral damage, buoys could help reduce anchor related coral damage. The discussions continued over time and over more beers without coming up with good answers for the issues raised.

In the fall of 1980, I became the first employee for the Key Largo National Marine Sanctuary (KLNMS), established in 1975 through the 1972 National Marine Sanctuary Program Act. The Superintendent of the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park was appointed the acting manager of KLNMS without the help of additional staff and funding support. Finally, significant funding became available to begin hiring needed staff to increase KLNMS capabilities and properly manage the KLMNS through a Federal State of Florida cooperative agreement.

During the first meeting with my state and federal supervisors, I was given a list of tasks that I was expected to initiate and complete over the next year. Reading over the list, I could see that I was going to be very busy, however, I stated that there is something else that is a very urgent problem. I explained the anchor damage issue, saying, “I want to develop and try an experimental mooring buoy design as a solution to the problem.” My new supervisors agreed and said: “That sounds good! Add that to your list and give us a budget.”

I came out of that meeting with a longer list of tasks but with an important mooring buoy development issue solved. I now had a funding source that helped me explore setting up mooring buoys in Key Largo.

But I still had several other issues to overcome. I had to figure out how to secure the buoy to the sea bottom in a way that would not harm fragile corals close by. A conventional mooring buoy at that time included a heavy weight or cement block and chain or cable to achieve holding power on a sand or mud bottom. Bob Soto in Grand Cayman and Don Stewart in Bonaire were putting together that kind of system on a small scale for their relatively small dive boats on sites that were almost always shielded from prevailing wind and wave action. That would not work with the larger boats and limited number of sand pockets within the popular reefs off of Key Largo with no protection from wind and sea conditions. Collateral damage could not be accepted. We needed a better mouse trap.

After getting the go-ahead on a materials budget, my first priority was to develop a secure anchor point for the buoy system. I was familiar with the technique used by my friends and marine science colleagues of coring into live boulder corals to extract a core sample to investigate the coral banding. They fill the void left behind with underwater cement. My plan was to core into dead solid limestone bottom substrate and cement a large eye bolt or similar device into the bottom that the mooring buoy line could be attached to.

With advice from my friend and welding shop owner, the late Gordon Cottrell, we designed a stainless-steel anchor point device (an anchor pin) to complete my coring hole plan.

In June 1981, Gene Shinn, director of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)-Fisher Island Station Miami, gave permission for two staff members, Harold Hudson and Dan Robbin, to come down to Key Largo with the USGS boat and hydraulic drilling equipment. The three of us installed the first six embedment anchor pins on French Reef off Key Largo.

I tried a variety of mooring array materials before I was able to make a final selection. The embedment anchor pins with a floating line to the surface worked as planned and caused no damage to the surrounding bottom substrate. Dive boat operators readily adapted to using the buoys and wanted to know when they could get more. My supervisors were happy with the results and added more to my budget to expand the system.

A few improvement modifications were made going forward. I later developed and added a soft bottom substrate embedment “Manta Ray” anchor along with a heavy-duty hard substrate embedment U-anchor for larger boats.

Q: What’s the biggest challenge in installing a mooring buoy?

A: Finding the best appropriate substrate to install the embedment mooring buoy anchor point can be challenging. For instance, on reef covered with branching corals, it’s difficult to locate a suitable place to drill.

Uncontrollable weather and sea state conditions can also make work difficult. However, sometimes the most difficult part of the process is dealing with equipment and materials shipping delays, including customs holdups when I’m in other countries.

Courtesy James HendeeHalas works on drilling a mooring buoy embedment hole.

Q: You have traveled the world over to help other countries install mooring buoy systems; what usually persuades a destination that it’s time to install buoys?

A: Usually persuasion is not an issue, but when dive resort customers point out anchor damage caused by the resort dive boat, that is persuasion enough to figure out a way to get buoys installed. In addition, there is peer pressure when they see other countries and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) use a mooring buoy system. Thus, mooring buoys in MPAs have become a management plan standard. Availability of funding then becomes the main hurdle, particularly in a non-MPA. Besides finding an initial installation funding source, a country must also acquire ongoing funding support for a long-term maintenance program.

Q: Do coral reefs still stand a chance, both in Florida and worldwide, and how can divers and readers help improve their odds of survival?

A: Unfortunately, we can’t do much about naturally occurring negative effects to coral reefs.

Deteriorating water quality—extreme nutrient loading, extreme salinity changes, extreme water temperature changes and excessive turbidity—have a negative effect on the marine environment and coral reefs, promoting algal blooms and coral diseases.

Some water-quality deterioration is unavoidable—such as that from major storms and global climate change.

Most divers learn as part of their training that coming too close to reefs can endanger their equipment, themselves and the corals. Diver buoyancy control can help reduce inadvertent, destructive diver contact with coral colonies.

Destructive boat groundings on shallow reefs can be reduced through education, safe boating practices and the installation of aids-to-navigation markers in problem areas. We help reduce physical anchor damage through the establishment of mooring buoy programs.

Everyone needs to pay attention to the work of reputable scientists in order to avoid adding to problems. Coral-transplanting projects on a small-scale offer hope for reefs in Florida and outside the continental U.S. Crown-of-thorns starfish-removal projects on certain overpopulated Pacific reefs have helped reduce destruction, with the recovery of some of those affected coral communities. Invasive lionfish removal projects help restore affected coral-community fish populations. It is important to support these efforts.

Q: What are the greatest challenges in marine conservation today?

A: Corals desperately need good water quality.

A lot of MPAs are established to maintain healthy fish stocks because there has been overfishing. It is difficult to balance the need of a fisherman to supply food for his family and make a living short-term, with the need to establish long-term sustainable fish stocks. The difficulty can be telling fishermen that some traditional areas may be closed, seasons restricted or size limits established. In the Florida Keys, we have found that mooring buoys and zone buoys have helped resolve some of these ongoing issues between user groups.

Q: What's been your most satisfying moment?

A: I went to Vietnam in 1968 as an army infantry unit commander and advisor to a Vietnamese military unit. Thirty-plus years later, I was able to go back to Vietnam multiple times to complete mooring buoy training and installation reef-protecting projects. On one of the return trips, I participated in a NOAA-organized multi-nation workshop. The workshop was well designed as a forum for marine environment protection information exchange between the United States, Vietnam, China and Cambodia. I served as a marine park resource manager specialist that included presenting a module on enforcement in marine parks.

Although the governing philosophy of the U.S. and Vietnam is quite different, it was very fulfilling and satisfying for me to return to Vietnam, not as a military combat leader, but as a marine environmental leader and advisor to help a country and its people in their endeavor to protect their marine environment.

Courtesy NOAA ArchivesHalas prioritized installing buoys on popular boating sites around Key Largo in the 1980s to protect coral reefs. His pioneering work established buoys as industry-standard in more than 38 countries worldwide, protecting untold acres of coral reefs from anchor damage.

Q: And your most surprising moment?

A: I was on a Komodo National Park boat off Komodo Island, Indonesia, preparing to install a mooring-buoy embedment anchor, when I heard a powerful explosion. It turned out that poachers were illegally fishing with dynamite nearby. Any diver in the water near an underwater explosion could be seriously injured by the blast.

Q: Who are your sea heroes?

A: [Scuba Diving’s 2014 Sea Hero of the Year] Ken Nedimyer, for his work in coral transplantation, and [Scuba Diving’s August 2014 Sea Hero] Lad Akins, for his work in invasive lionfish control.

Q: What’s next for John Halas?

A: For the past few years in my “semi”-retirement, I have been engaged in water sampling and buoy maintenance contract work related to an ocean acidification research-monitoring buoy deployed off Islamorada, Florida. The project is administered and conducted through the NOAA Coral Health and Monitoring Program (CHAMP) at the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) Research Institute in Miami.

In addition, I have been working contractually with the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (5 Cs), an entity based out of Belmopan, Belize, with a mission to support the Caribbean people as they address the effects of climate change. For the past several years, 5 Cs has been collaborating with the NOAA-CHAMP Coral Reef Early Warning System (CREWS) Program to establish oceanographic and meteorological monitoring stations. We are using my mooring buoy embedment anchor technology with a team effort to install CREWS scientific monitoring stations in the waters around eight Caribbean island nations in the western Atlantic and Caribbean as well as Belize. Funding for these projects comes through NOAA-CHAMP and through 5 Cs grant sources, which are the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Union. Host countries must commit to contributing resources for their respective country’s buoys.

The CREWS buoy stations are designed to collect and transmit oceanographic and meteorological data to NOAA-AOML, where the data is processed and disseminated via the internet to scientists and the public to better understand changes that may or may not be occurring on reef systems in the Caribbean Sea. Plans to upgrade the first series of buoys and add additional buoys designed to ring the Caribbean in 2020 were put on hold with the COVID-19 outbreak. However, the project is set to continue when travel clearance is given and it is deemed safe to proceed with the first new planned CREWS site in the Bahamas. Additional information on CHAMP and the CREWS project is available on the internet (NOAA/CHAMP/CREWS) and 5 Cs at www.caribbeanclimate.bz.

Each Sea Hero featured in Scuba Diving receives a Seiko Prospex SRPE05 watch valued at $595. For our December issue, judges select a Sea Hero of the Year, who receives a $5,000 cash award from Seiko to further his or her work. Nominate a sea hero at /seaheroes.