Sea Urchins are Killing a Millennia-Old Culture. Can Divers Save it?

Blake Tallman began his first job at age 3.

A large rinse tank sat behind Sub-Surface Progression, his father’s dive shop, in the late 1980s. “I’d be jumping on the wetsuits, making sure they’d get all submerged and cleaned, from all the rentals getting returned,” he says.

Splashing away between the Pacific Coast Highway and the jagged Mendocino cliffs in Fort Bragg, he usually wore a miniature wetsuit his father, Kenny, had custom-made for him. There was a lot of jumping to be done during abalone season, which in Northern California ran from the start of April to the end of November.

Courtesy Blake TallmanBlake Tallman swims with his father Kenny (circa 1990).

Sub-Surface Progression’s ab package—which included freediving gear, a surface float and a bar for popping the sea snail off rocks—pulled tourists and locals alike to the low building. Inside, abalone shells large and small hung from rafters, spiraled on a plywood canvas and sat encased in glass, showing shoppers what waited below the waves. On busy weekends, the store could run through all of its 100 kits.

That was, until the abalone disappeared.

The kelp went first, taken out by what’s now referred to as “the perfect storm.” Sea star wasting disease decimated California’s sea star population starting in 2013, leading to a boom of native purple urchin. The urchins began feasting on the kelp, wiping out entire underwater forests and leaving miles of ocean floor devoid of any life but their own.

Around the same time the water heated up. A warm blob of ocean water descended on California, intensified by additional toasty water from El Niño in subsequent years.

By 2016, unfettered urchin feasts and witheringly warm water destroyed more than 90 percent of California’s kelp forests, which have yet to recover.

“Losing kelp meant that climate change was here and happening now and in your back yard,” says Tristin McHugh, the Northern California regional manager at Reef Check, a global reef monitoring nonprofit.

Abalone, which feeds on kelp, couldn’t withstand the loss. With already precarious population levels from decades of overfishing, the sea snail quickly began to disappear.

Courtesy Blake TallmanSub-Surface Progression in Fort Bragg, California.

Tallman, who had taken over the shop at age 20 when Kenny died of leukemia, witnessed the underwater catastrophe firsthand. In 2015, as the waters continued to warm, he took a routine, mile-long swim down the coast between Casper Cove and Jug Handle, popular abalone diving spots.

“There’s usually—not even exaggerating—probably millions of abalone,” he says, “and I think I saw one.”

Finally, in 2018, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife cancelled the Northern California abalone fishing season for a year to give the snail space to recover. Tallman watched 80 percent of his business disappear overnight.

He decided to do all he could to scrape through. He would be there if the abalone came back next year and, with them, California’s ab divers.

An Endless Allure

As long as people have lived along the Pacific shoreline, they have eaten abalone meat and admired its pearly shells.

Native Americans have harvested abalone from the Pacific’s shallows for more than 10,000 years, according to historic records. In a fishing style known today as rock picking, tribes searched the shallows for abalone, harvesting them without boats or dive gear. They ate the meat, using the shells for jewelry, ceremony, fishing hooks, boat decorations and trading.

Today, abalone are still used for “everything,” says Javier Silva, member of the Sherwood Valley Band of Pomo Indians and of the state's administrative team during California's 2019 review of recreational red abalone management strategies. “We use it for ceremony, use it for subsistence, we wear it on our regalia when dancing, we use it for smudging. It’s a very sacred animal.”

Courtesy Javier SilvaJavier Silva searches for abalone in the shallows of Point North in Westport, California.

Chinese-American immigrants opened the first of California’s commercial abalone fisheries in the 1850s. They prospered as rock pickers for 40 years, before anti-Chinese laws and a 1900 ban on shallow water abalone fishing put them out of business.

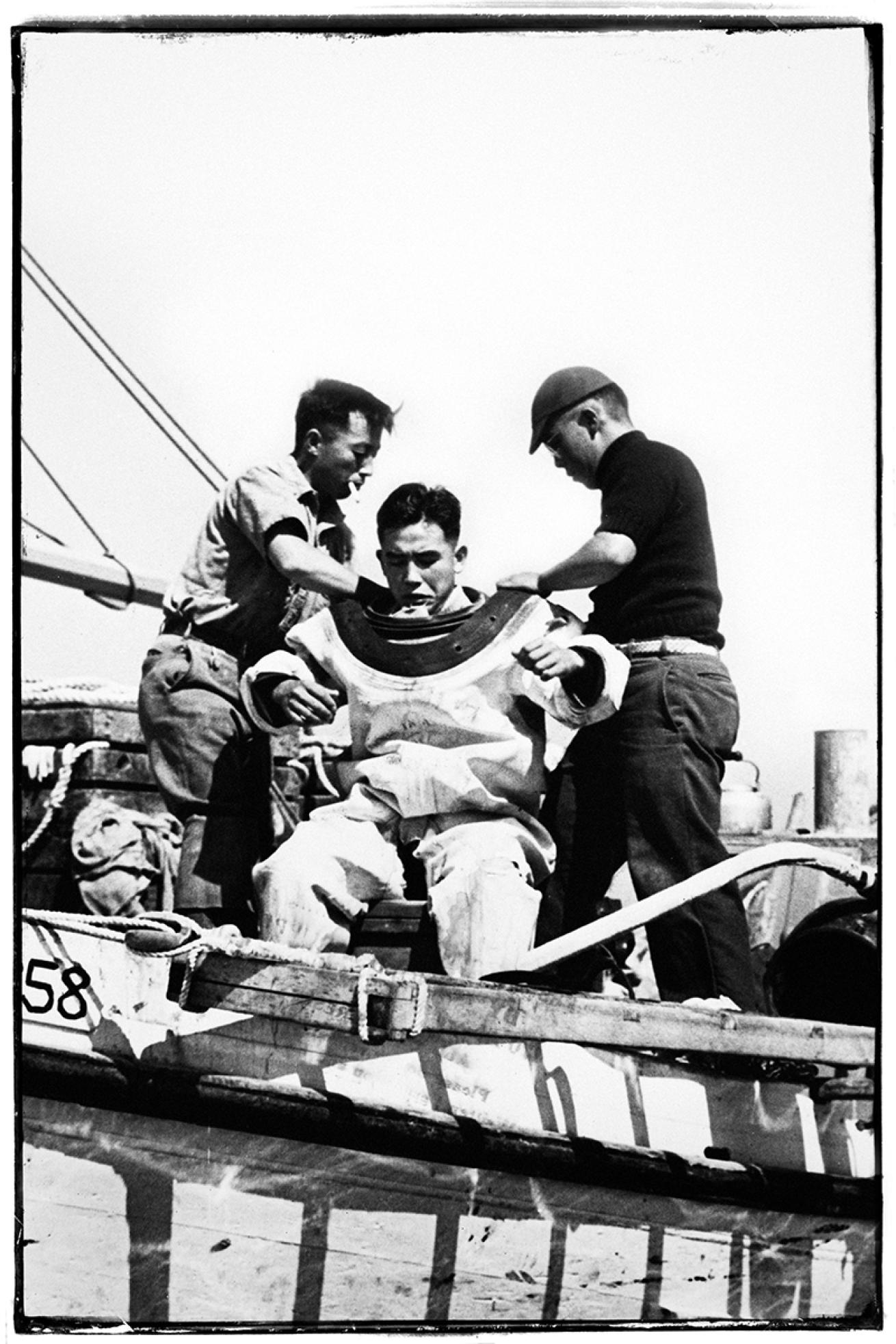

Mr. Pat Hathaway Photo CollectionA Japanese diver gears up at Point Lobos in 1938. (CAViews.com)

Then came the Japanese fisheries, the first of California’s recorded abalone divers. Japanese women began freediving for abalone thousands of years ago, and men in America adapted the practice for commercial fishing. Freediving dominated initially, with hard helmets and hookah added as diving technology evolved. WWII internment laws wiped these fisheries off the map as divers were forcibly relocated to camps. Commercial harvesting initially slowed in their absence, before Euro-American fisheries picked up pace to supply Americans with wartime sustenance.

As Californian sects vied for control, unsustainable fishing practices undermined the entire industry. Commercial and recreational fisheries sporadically closed and reopened, and catch limits dwindled as abalone waned. Abundant abs near the shore could themselves have been a sign of an imbalanced ecosystem, says McHugh. The fur trade drove the otter—a key abalone predator—into functional extinction along the California coast around 1840, roughly a decade before the first commercial fisheries began. Abalone may have prospered without a natural predator; as otter recovered along the middle of the coast during the late 1900s — from Point Conception to the San Francisco Bay — they remained absent in Northern California waters.

By the turn of the century only one abalone fishery remained: the Northern California recreational fishery. It spawned a thriving tourism industry, with campgrounds, hotels, restaurants and stores catering to abalone divers.

“It’s just such a rare thing that people loved it,” says Tallman.

Abalone vacations became annual traditions, with parents teaching their children how to dive for and cook abalone over a campground fire surrounded by friends. “You’d go through the campground and it sounds like a housing development with all the hammers pounding abalone,” softening the meat for frying, says Joshua Russo, a recreational abalone diver of two decades and member of the state’s Recreational Abalone Advisory Committee.

Brandon ColeThe Northern California recreational abalone fishery became a $44 million tourism industry beloved by generations of divers.

A single abalone could feed a family, and the World Championship Abalone Cook-Off launched at a dive shop in the 1980s. It became a long-standing tradition in Fort Bragg, where participants could revel in fried abalone diced into salsa, sausage and ceviche, or wrapped in bacon, cheese or dates.

Competitive spirits ran high during ab season, with divers vying to find trophy shells longer than 10 inches. Some jealously hid the location of their favorite dive spots, while others dared themselves to go where many wouldn’t venture to have the boldest stories. Every year a few pushed the limits too far, with several divers drowning annually.

Abalone adoration pushed the black market value of a single snail to $100 in the early 2000s, says Sonke Mastrup, environmental program manager of the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Invertebrate Program. Californians unwilling to endure the rugged surf illegally bought dinner from licensed divers and poachers alike. Others illicitly bartered their catch for car repairs or dental procedures. To fight abalone poaching, the DFW monitored shorelines, ran vehicular check-points and set up abalone black market stings.

All the while, the popularity of abalone diving grew. More than 38,000 licensed divers harvested an estimated 728,000 abalone in 2000, up from an average of 685,000 abalone annually between 1983 and 1989, according to state data.

Crumbling Overnight

As love for abalone continued pulsing on shore, early warning signs began showing up under water. Divers had to go to progressively deeper waters in search of abalone clusters as early as the late 1990s, according to diver-reported collecting data.

Abalone restrictions steadily tightened over the next two decades. The DFW capped divers’ annual take at 100 in 2000, a restriction that fell as low as nine per year in Sonoma and Marin counties by 2014. By the time the kelp forests withered in 2016, the department convened public meetings about dropping the limit further.

“The debate was: How do we do this reduction and affect as few people as possible?” says Russo. “Nobody wants to be irresponsible with the resource, but we have to weigh that with what the decisions are going to do to people fiscally, especially when you’re talking about...an entire community.”

It was a community already suffering. Purple urchins had outcompeted their more valuable red cousins, damaging the area’s red urchin fishery. Nobody wanted to lose $44 million in abalone tourism too.

But a new limit was never reached. Abalone levels crumbled so low in 2017 the fishing season was cancelled for 2018, a closure that’s now being extended to at least 2026.

The decision sparked a divided community reaction, broke apart the Northern California dive community and cut the state’s northern Native American tribes off from hunting as they have for thousands of years.

“When they closed the recreational red abalone, there was a reason there was an uproar, and that was because of the state-tribal jurisdiction issues around hunting and fishing and gathering,” says Silva. Some tribal members believe the state does not have the right to limit their abalone collection and continue to hunt it, risking hefty fines and lifelong loss of state hunting licenses if they are caught.

Courtesy Blake TallmanJoshua Russo (left) stands with Blake (right) and Seidon Tallman (middle). Russo gifted Blake Tallman with an Amadeo Bachar print when Sub-Surface Progression closed as a thank you gift to express what the dive shop meant to the community during its 43 years in business.

Silva responded by joining the state’s abalone management review to ensure Native American voices are heard. “I took that role as I have had an obligation to my great-grandparents, my family,” he says.

As for the communities reliant on abalone tourism, Tallman says an initially divided public came to mostly support the closure as underwater conditions continued to degrade. He is among the supporters, even though Sub-Surface Progression’s years following the closure were “pretty depressing.” Freediving classes, spearfishing gear and kayak rentals could not replace the abalone business.

“The closure of abalone diving was devastating to the Northern California dive community,” he said. “When people would go abalone diving, they’d get this food that was rare and they share...with their friends who’d never had it before. They’d have a cool, beautiful shell that they hang on their wall... And now that’s lost.”

In December of 2019, two years after the ab closure, Tallman permanently shut the doors of his shop. The last dive shop on the Northern California coast was no more.

That same month, his second son was born. Rainier, named for the mountain, joined four-year-old brother Seidon, named for the Greek sea god in his grandfather’s honor—the first generation on America’s Pacific coast likely to grow up without abalone fishing.

Look for the Kelp-ers

Courtesy Alberto Richard/The Purple Nightmare!Recreational divers pour bagged urchins into a bin during a volunteer culling event at Ocean Cove, California.

Joshua Russo stood on the beach of Ocean Cove on May 12, 2018, watching kayakers bob on the water as crowds bustled around him on the beach.

Unseen were the dozens of divers below the waves, bagging purple urchins. The kayakers floating in Russo’s view waited for one to ascend with bulging sacks, or carried bags of freshly caught urchins to shore after sending a diver back to the ocean floor with a fresh pouch. Those on the beach lent a hand crushing the periwinkle pests.

“It was an orchestra,” says Russo. And he was the conductor.

Kelp’s collapse entered Russo’s world in 2014 at a presentation given to the Recreational Abalone Advisory Committee by a California DFW scientist. He immediately began agitating the state to increase the daily catch limit of purple urchins, believing the change would raise public awareness of the kelp die-off. The devoted abalone guide wanted to see action before the entire underwater ecosystem collapsed.

But the gears of government clank slowly, and only after the fishery closure did he convince the Fish and Game Commission to increase the limit from 35 individuals to 20 gallons, with a later hike to 40 gallons.

It was enough to launch the first recreational culling dives, gathering press and public momentum. The plans, however, immediately drew concerns from the DFW, animal activists, hunters and Native Americans alike, worried about unnecessary killing of a native species.

“I know that these people care,” Silva says, and that it is human nature to take action. But “maybe we did do something about it and that’s why it’s a situation.” He would prefer to let time heal nature’s wounds.

Courtesy Alberto Richard/The Purple Nightmare!Joshua Russo (left) speaks with then-Department of Fish and Wildlife scientist Dr. Cynthia Catton during an urchin culling event.

“I think what holds people back is that they don’t realize this is a restoration,” says Russo. “We’re just removing them from the ocean and crushing them...so even a really conservative hunter would say that that’s wasting it. But the thing is our goal is to restore balance in the ocean.”

After Russo’s first event in Ocean’s Cove, he planned an urchin removal dive every other month, rotating between Sonoma and Mendocino counties, prioritizing shore-diving access. Hundreds of volunteers participated from across California, including Tallman, who donated gear rentals and air tanks to help get people in the water.

In addition to the recreational dives, Russo raised $130,000 to pay the region’s commercial red urchin divers to instead collect purple urchins, addressing urchin barrens resting deeper than his volunteers could descend. He succeeded in extracting millions of purple urchins and helping convince the state it was an issue worth tackling.

Mike Esgro/Ocean Protection CouncilPurple urchins rest onshore after a commercial collection effort.

The problem: There was no data to show if his work actually helped kelp return.

Recreational divers spending hours underwater harvesting urchins wanted to know if it was working, says Reef Check’s McHugh, whose father was a recreational abalone diver. “And it kind of broke my heart to say no, and also that we don’t know.”

While rotating between shore-accessible coves made it easier for divers to participate, it dispersed the collection efforts to biologically random areas. With hundreds of miles of decimated coastline, it would take a tighter system to see if human removal could have an impact.

Today, recreational, commercial and scientific divers are coordinating with state of California funding to participate in a concentrated urchin removal in two Mendocino county coves. The groups want to find out if concentrating culling efforts can reduce urchin populations enough that the kelp ecosystem can recover in that specific area. Both refuges have maintained small crops of kelp since the die-offs began, so the hope is to create a seed bank for spreading kelp once conditions improve.

Commercial divers are tending Noyo Harbor, cleaning swim lanes created by McHugh’s team with a benthic cable. Once collecting is done for the day, Reef Check purchases their catch with funding from a California Ocean Protection Council grant. After assessing a sample of the urchins’ size and diet, Reef Check sends them to an organic composting facility.

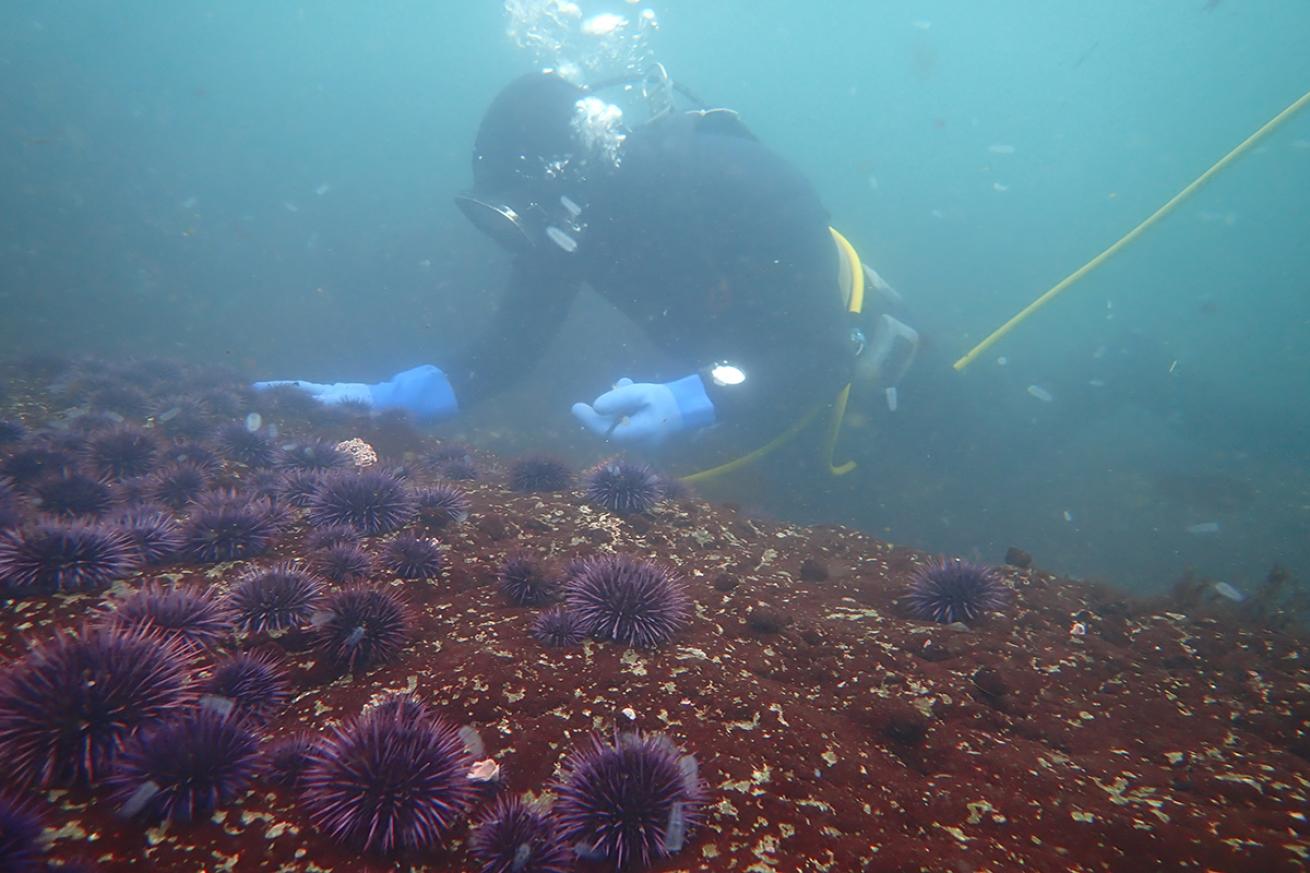

Reef CheckA commercial diver culls purple urchins in Noyo Harbor.

Reef Check’s scientific divers are monitoring the situation under the water at Noyo, as well as another, yet-again controversial recreational dive effort in Casper Cove.

Rather than hauling bags of urchins to the surface, recreational divers are crushing Casper Cove urchins in place. Doing this is illegal everywhere else in California. Urchins are broadcast spawners, and there is concern that smashing a broadcast spawner will induce reproduction, augmenting the urchin overabundance.

The advantage to crushing underwater is speed. Crushing is “immensely more efficient,” says Russo. Some divers think “they can crush ten times the amount of urchins they could have removed,” potentially accelerating restoration results.

“We don’t necessarily have the science to support it or deny it one way or another,” says McHugh. “And we’re at this moment in history where we really want some truth here. We want to understand how things are operating and how they look in the face of climate change. And so the reason why 2020 is the year to go for it is really because of the necessity of the climate issue. We really need to tackle this head on this year and start addressing some of these very fundamental questions that threaten our existence.”

As of mid-September, the joint removal efforts have extracted nearly 22,000 pounds of urchins from Mendocino’s seafloor.

Divvying Up Revival

McHugh and others are hopeful that 2020 is a turning point for the state’s kelp. The ocean is cooler than the last several years and some kelp forests — including those in Noyo and Casper — are re-seeding on their own. But climate instability could reverse the progress, and even if kelp recovers quickly, thriving abalone sits on a far horizon. The sea snail breeds at a snail’s pace; it takes 12 years to hit reproductive age, and even then only successfully spawns every few years.

“How long until we see a population like we had in 2015 [before the crash]? Probably 40 years,” says DFW’s Mastrup.

Brandon Cole"Recreational divers spending hours underwater harvesting urchins wanted to know if it was working," says Reef Check’s McHugh, whose father was a recreational abalone diver. "And it kind of broke my heart to say no, and also that we don’t know."

The projection is a reckoning. A decades-long closure means older fishermen may never see another dive season, pushing some to disengage with the sport entirely. Others engage fiercely with management deliberations, worried about how the next generation of divers will learn to properly pop an ab.

“You can’t run a fishery unless the public supports it” or else widespread poaching breaks out, says Mastrup. “So there’s a social contract, so to speak, you have to maintain with the public that what we’re doing is wise, is the right path and is supported. And that’s going to be hard when you’re saying some of you will never fish again."

To ease these tensions, he hopes a de minimis fishery can open between now and a full recovery. Mastrup envisions a tight allotment of licenses given out via lottery, and participating divers would have to bring their catch to a checkpoint for scientific assessment before taking the meat home. But reopening the fishery in any way will require answering difficult questions about who gets access to climate-stressed resources, and in what order.

If there’s a limit on the total number of abalone that can be caught, how many go to the tribes and how many go to sportfishers? What are the best metrics for making that choice? How much should it cost to take part in a fishery that needs restoration funding, but wants to provide equitable access?

“Some [questions] we have answers for,” says Mastrup. “Others, we’re still working on the details.”

Until then, Tallman plans to raise his sons on stories. Stories of fish and friends and flames. Stories about sneaking up on your dinner, stories of the time-I-found-an-ab-so-big-you-just-wouldn’t-believe.

“I definitely think about that all the time,” he says. He is full of plans to give his sons the salt life: boogie boarding, surfing, tide pooling, snorkeling. And “eventually, out in the ocean, being able to point out an abalone.”

Related: