Dolphins in Captivity?

Dolphin programs connect people with the oceans and provide valuable scientific information that helps wild populations.

By Art Cooper Art Cooper is vice president of operations for Dolphins Plus in Key Largo, Florida, and manages a staff of dedicated marine-mammal trainers and conservationists. He assists the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, and helps rescue sick and injured marine mammals throughout the southeastern United States. Prior to the 1972 passage of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act, dolphins and whales weren’t held in particularly high regard and were at great risk. But in the mid-1960s, a new wave of marine-life facilities transformed the public interest from apathy to fascination. In fact, you could argue that the Act was a direct result of people becoming more interested in the preservation of wild dolphins by visiting marine-life research and education centers. Facilities like Dolphins Plus in Key Largo, Florida, have been catalysts for the increased awareness of our oceans, and their programs have helped educate millions of students about marine mammals through shows and animal interactions. Dolphins Plus and other marine-mammal parks support a common mission to provide people with opportunities to expand their knowledge about marine-mammal biology and intelligence, promote sensitivity toward the marine environment, and inspire visitors to take action in marine conservation and wildlife protection. Critics of zoos and aquariums often portray life in the wild as much safer, healthier and even idyllic for animals. This characterization is far from reality. An annual report to congress by the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission reveals that more whales, dolphins and porpoises die every year by getting entangled in fishing gear than from any other cause. And while bottlenose dolphins, the most common species found in captivity, are not endangered, managed care by humans might be the only hope for other highly endangered dolphins in the wild. Knowledge gained from marine mammals housed in zoos and aquariums has led to the discoveries and diagnoses of many diseases including morbillivirus, a viral disease currently devastating the mid-Atlantic bottlenose-dolphin population. Vaccines are being developed by analyzing healthy blood serum collected from trained dolphins, which scientists have been able to compare with sick and injured animals’ blood in the field, increasing their effectiveness in diagnosing and treating illnesses. The National Marine Fisheries Service relies on the assistance of organizations such as Dolphins Plus and others to help rescue dolphins in distress. And hundreds of whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, shore birds and sea turtles have been rescued, rehabilitated and released back into the wild. With modern, interactive swim programs, dolphins living in marine-life facilities give guests a profound personal experience, which greatly enhances their desire to conserve and protect our oceans. This level of education simply cannot be imparted in classrooms or books.

Tanks are for brewing beer — not imprisoning dolphins.

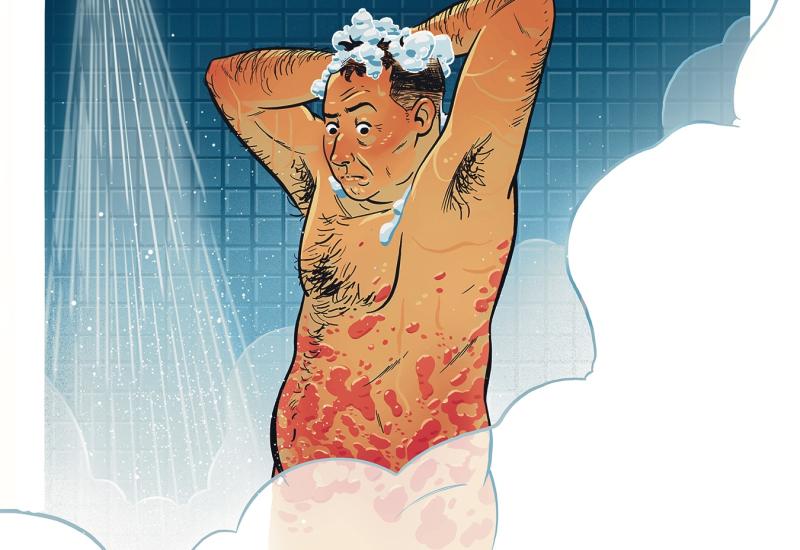

By Louie Psihoyos Louie Psihoyos is the executive director of the Oceanic Preservation Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to using photography and film to inspire change to help preserve the world’s oceans. He is also the director of the upcoming documentary _The Cove, which examines dolphin capture in Japan._ Swimming with dolphins might be one of the most transcendental events in any diver’s life. They are one of the only wild animals known to routinely save the lives of humans in need. Three years ago off the coast of Rangiroa, French Polynesia, a resident pod of dolphins was swimming with a dive group I was part of. For 45 minutes, they darted swiftly through us until suddenly taking off. For a few seconds I was saddened, but soon realized that they had left us to ward off an oncoming great hammerhead shark. My feeling now, after five years of observing the captive dolphin trade, is that experiences with dolphins should happen only in the wild. Let me explain. The dolphin-capture process, which I have witnessed many times in Taiji, Japan, where most dolphins for dolphinariums (dolphin aquariums) and swim-with-dolphin programs come from, is a very violent process. Dolphins have larger brains than humans and have an extra sense, sonar, their most valuable asset. Dolphins literally see with sound and also hunt and communicate using it. During the dolphin hunting season in Japan — September to March — about a dozen fast boats cruise along the animals’ migratory routes and wait. When the pods pass, hunters lower long poles into the water and bang on them, creating a wall of sound that frightens the dolphins into frantically swimming away. To them, the banging of the poles must be comparable to humans being blasted by the noise of jet engines just above their heads. The noise forces the dolphins into a cove, which hunters seal with nets. The next morning, representatives of dolphinariums from all over the world select dolphins for their parks. During this process, the dolphins, which are extremely social in nature, are ripped from their pods. Young females are the most highly sought after because they are easier to train than males. Those that are rejected — males, blemished ones, or dolphins considered too young or too old — are then slaughtered for their meat. The captured dolphins end up in concrete tanks and their sonar becomes a relic of their former natural existence. In these tanks they’re starved and then forced to perform a multitude of stupid tricks for human amusement. The owner of one of the largest captive dolphin marine parks is also one of the world’s largest beer producers. Let me say it plainly: Tanks are better used for brewing beer. Members of the captive-dolphin industry might argue that dolphins are our ambassadors to the oceans. They claim that children will learn to love the oceans through exposure to these small whales. Yet by capturing and confining dolphins we’re actually teaching our children to subjugate animals with bigger brains than our own, condone the breaking up of dolphins’ social structures, rationalize killing their parents and mates, cut them off from their primordial sense and then train them to do tricks for food. That’s a poor way to sensitize our children to the intelligence of these amazing animals. If that’s education, then we need to rethink the approach. Captivity is also extremely stressful to dolphins. They develop ulcers and other stress-related diseases. Dolphin traffickers claim that nature is stressful, and dolphins don’t have to worry about their next meal in captivity. But the health and life expectancy of animals in most dolphinariums doesn’t support that claim. As for the argument that some dolphins were born into captivity, as heads of dolphin parks often claim, I counter that captivity is still slavery, even if those dolphins never knew freedom. Ric O’Barry — who captured and trained the original five female dolphins that collectively played the part of Flipper on the 1960s television show of the same name —says in our film, The Cove, that the dolphin smile is nature’s worst deception, creating the illusion that dolphins are always happy. To see a trailer for The Cove, opening this July in select theaters, visit www.scubadiving.com/links.

Dolphin programs connect people with the oceans and provide valuable scientific information that helps wild populations.

By Art Cooper Art Cooper is vice president of operations for Dolphins Plus in Key Largo, Florida, and manages a staff of dedicated marine-mammal trainers and conservationists. He assists the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, and helps rescue sick and injured marine mammals throughout the southeastern United States. Prior to the 1972 passage of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act, dolphins and whales weren’t held in particularly high regard and were at great risk. But in the mid-1960s, a new wave of marine-life facilities transformed the public interest from apathy to fascination. In fact, you could argue that the Act was a direct result of people becoming more interested in the preservation of wild dolphins by visiting marine-life research and education centers. Facilities like Dolphins Plus in Key Largo, Florida, have been catalysts for the increased awareness of our oceans, and their programs have helped educate millions of students about marine mammals through shows and animal interactions. Dolphins Plus and other marine-mammal parks support a common mission to provide people with opportunities to expand their knowledge about marine-mammal biology and intelligence, promote sensitivity toward the marine environment, and inspire visitors to take action in marine conservation and wildlife protection. Critics of zoos and aquariums often portray life in the wild as much safer, healthier and even idyllic for animals. This characterization is far from reality. An annual report to congress by the U.S. Marine Mammal Commission reveals that more whales, dolphins and porpoises die every year by getting entangled in fishing gear than from any other cause. And while bottlenose dolphins, the most common species found in captivity, are not endangered, managed care by humans might be the only hope for other highly endangered dolphins in the wild. Knowledge gained from marine mammals housed in zoos and aquariums has led to the discoveries and diagnoses of many diseases including morbillivirus, a viral disease currently devastating the mid-Atlantic bottlenose-dolphin population. Vaccines are being developed by analyzing healthy blood serum collected from trained dolphins, which scientists have been able to compare with sick and injured animals’ blood in the field, increasing their effectiveness in diagnosing and treating illnesses. The National Marine Fisheries Service relies on the assistance of organizations such as Dolphins Plus and others to help rescue dolphins in distress. And hundreds of whales, dolphins, seals, sea lions, shore birds and sea turtles have been rescued, rehabilitated and released back into the wild. With modern, interactive swim programs, dolphins living in marine-life facilities give guests a profound personal experience, which greatly enhances their desire to conserve and protect our oceans. This level of education simply cannot be imparted in classrooms or books.

Tanks are for brewing beer — not imprisoning dolphins.

By Louie Psihoyos Louie Psihoyos is the executive director of the Oceanic Preservation Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to using photography and film to inspire change to help preserve the world’s oceans. He is also the director of the upcoming documentary _The Cove, which examines dolphin capture in Japan._ Swimming with dolphins might be one of the most transcendental events in any diver’s life. They are one of the only wild animals known to routinely save the lives of humans in need. Three years ago off the coast of Rangiroa, French Polynesia, a resident pod of dolphins was swimming with a dive group I was part of. For 45 minutes, they darted swiftly through us until suddenly taking off. For a few seconds I was saddened, but soon realized that they had left us to ward off an oncoming great hammerhead shark. My feeling now, after five years of observing the captive dolphin trade, is that experiences with dolphins should happen only in the wild. Let me explain. The dolphin-capture process, which I have witnessed many times in Taiji, Japan, where most dolphins for dolphinariums (dolphin aquariums) and swim-with-dolphin programs come from, is a very violent process. Dolphins have larger brains than humans and have an extra sense, sonar, their most valuable asset. Dolphins literally see with sound and also hunt and communicate using it. During the dolphin hunting season in Japan — September to March — about a dozen fast boats cruise along the animals’ migratory routes and wait. When the pods pass, hunters lower long poles into the water and bang on them, creating a wall of sound that frightens the dolphins into frantically swimming away. To them, the banging of the poles must be comparable to humans being blasted by the noise of jet engines just above their heads. The noise forces the dolphins into a cove, which hunters seal with nets. The next morning, representatives of dolphinariums from all over the world select dolphins for their parks. During this process, the dolphins, which are extremely social in nature, are ripped from their pods. Young females are the most highly sought after because they are easier to train than males. Those that are rejected — males, blemished ones, or dolphins considered too young or too old — are then slaughtered for their meat. The captured dolphins end up in concrete tanks and their sonar becomes a relic of their former natural existence. In these tanks they’re starved and then forced to perform a multitude of stupid tricks for human amusement. The owner of one of the largest captive dolphin marine parks is also one of the world’s largest beer producers. Let me say it plainly: Tanks are better used for brewing beer. Members of the captive-dolphin industry might argue that dolphins are our ambassadors to the oceans. They claim that children will learn to love the oceans through exposure to these small whales. Yet by capturing and confining dolphins we’re actually teaching our children to subjugate animals with bigger brains than our own, condone the breaking up of dolphins’ social structures, rationalize killing their parents and mates, cut them off from their primordial sense and then train them to do tricks for food. That’s a poor way to sensitize our children to the intelligence of these amazing animals. If that’s education, then we need to rethink the approach. Captivity is also extremely stressful to dolphins. They develop ulcers and other stress-related diseases. Dolphin traffickers claim that nature is stressful, and dolphins don’t have to worry about their next meal in captivity. But the health and life expectancy of animals in most dolphinariums doesn’t support that claim. As for the argument that some dolphins were born into captivity, as heads of dolphin parks often claim, I counter that captivity is still slavery, even if those dolphins never knew freedom. Ric O’Barry — who captured and trained the original five female dolphins that collectively played the part of Flipper on the 1960s television show of the same name —says in our film, The Cove, that the dolphin smile is nature’s worst deception, creating the illusion that dolphins are always happy. To see a trailer for The Cove, opening this July in select theaters, visit www.scubadiving.com/links.