What Underwater Photographers Need to Know About the Galapagos

Alex MustardIn the strongest currents, leave your strobes on the boat and shoot using available light.

Bucket list is a phrase that always comes up when divers talk about the Galapagos Islands. The unique location comes with a lofty entry price and promises big animals in numbers and diversity that almost nowhere else can match. The “but” is that Galapagos diving is often very challenging, particularly when your goal is photography. The conditions are hard to predict: The water is regularly cold; visibility can be poor. At times the raging currents even make it difficult to point your camera in the right direction.

Tip 1: Prep Makes Perfect

Four major ocean currents converge on Galapagos and supercharge the entire marine food chain. These waters are packed with fish, which provide for large populations of rays, whales, dolphins, sea lions and lots of sharks (hammerhead, silky, Galapagos and huge whale sharks).

Photography in Galapagos is focused on these phenomenal subjects, but limited by the conditions. Good preparation is essential for maximizing your success— and that starts with equipment. The unpredictable nature of the conditions and encounters makes this the realm of the wide-angle zoom lens.

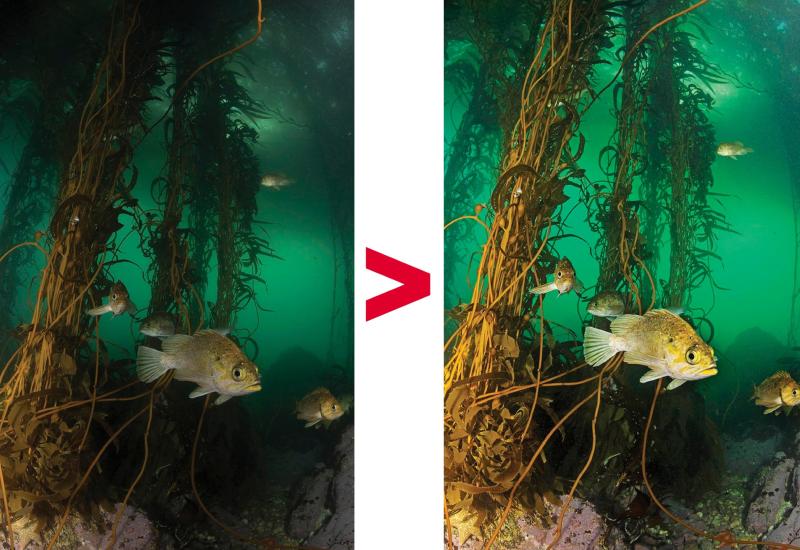

On my last trip, I dived mostly with the Nauticam WACP-1, occasionally switching it out for my fisheye. Go with long strobe arms because most subjects are shot through a fair amount of water. However, when currents are forecast to be especially fierce by the guides, you might want to do a few dives without strobes at all. This makes the camera much easier to handle. While others struggle to get anything, you’ll have a memory card full of clean available-light shots and striking silhouettes.

Alex MustardStay low, stay still and minimize your bubbles for a close pass.

All dives in the Galapagos are led by licensed National Park Service dive guides, and often you are instructed to settle among the rocks. Kevlar-reinforced gloves provide warmth and protection, but you may want a thinner, more dexterous glove on your right hand to help you operate all the important camera controls, or consider trimming off the fingers and thumb on the right glove to help. Copying the dive guides, I use long, powerful freediving fins in Galapagos. These aren’t the fins for fine maneuvering in delicate environments, but are well-suited to getting close pelagic encounters or holding position against a strong flow in the open water. Finally, use a good lanyard or clip for the camera to enable you to deploy your DSMB or safety sausage from depth, before drifting away from the reef at the end of dives.

Tip 2: Stellar Subjects

Galapagos is the sharkiest place on Earth, and scalloped hammerheads are the iconic species. They are abundant but wary, and not typically easy to photograph. The dive group descends with the guide and waits close to a cleaning station, usually operated by barberfish (a yellow butterflyfish) or attractive king angelfish. Get secure in the current and get settings dialed in. I always set up for a good pass—I prefer to be optimized if I get lucky with a good encounter rather than set up for more distant shots and then ruin a close pass.

Place strobes out wide to minimize backscatter, with their power turned up and the camera’s aperture open a little more than usual to help get flash on the subject. Next, adjust the ISO so that shooting just upward of horizontal you end up with a shutter speed of about 1/125. This gives you flexibility to adjust the shutter speed down when shooting down the slope and up when shooting toward the surface, depending on where the sharks end up.

Hammerheads don’t like bubbles. Try to position yourself at one end of the group. Don’t hold your breath, but when the hammers are coming in, breathe so slowly that no bubbles are coming out for those critical moments! The other species of sharks and rays are less tricky. Galapagos sharks often make reliable circles; if you hide behind a boulder on their standard circuit, you should get frame-fillers. The same tactic works with eagle rays. Silky sharks tend to show up in the blue at the end of the dive and come in closer as divers surface. Waiting until the end can often yield the best pictures.

Whale sharks usually appear with little warning in the blue. If the shark is already alongside you, then you won’t overtake it and it is often better to stay put and just enjoy the view. The whale sharks in Galapagos are large adults, much bigger than what is usually seen in other places, and can look amazing surrounded by the dense fish life.

Galapagos offers countless other photo opportunities, including endemic Galapagos sea lions, Galapagos penguins and the enigmatic marine iguana. But perhaps the most addictive aspect of photography in Galapagos is that you feel absolutely anything can appear in front of your lens at any time. And, more often than not, it does. The better prepared you are, the better your images will be.