Marine Science in Action: Cabo Pulmo National Park

Octavio AburtoHealthy schools of fish are common at sites like El Bajo Reef.

Octavio AburtoThe macro life in Cabo Pulmo National Park is also thriving. Here, a jawfish is excavating a burrow in the reef.

Octavio Aburto

Octavio AburtoIn business since 1995, Cabo Pulmo Divers can put divers on the marine park's best dive sites. Says photographer Octavio Aburto: “Jacques Cousteau called the Gulf of California the aquarium of the world. In many places, it isn’t any more. But when I dive Cabo Pulmo, I understand. It is like diving in an aquarium.”

As a small girl, Judith Castro remembers her father and brothers returning from longer and longer fishing trips with less and less to show for their work. Several generations of her family had made a living by pearl diving and fishing out of Cabo Pulmo, a small, remote village on Baja California’s east side. But the once-thriving reefs scattered off the village’s beach, and much of the rest of the Gulf of California, had been fished out.

Then, in the early 1980s, scientists from the University of Baja California Sur came to town to talk about the valuable natural resources around Cabo Pulmo, recalls Castro, now 39. Divers began to visit too, and for the first time, locals looked through dive masks at coral reefs 30 to 60 feet beneath the clear blue waters — and decided to stop fishing.

No one was quite sure what to do instead though. One of Judith’s brothers, Mario, went to Cabo San Lucas searching for employment and ended up learning to scuba dive. He returned to open a dive shop, Cabo Pulmo Sport Center, in 1991.

“We started to protect our reef, telling people to take care of it, and then decided to ask the government to make it an official protected area,” Judith says. It took a lot of work and time, but on June 6, 1995, the Mexican government created the 17,500-acre, mostly underwater Cabo Pulmo National Park. Jose Luis “Pepe” Murietta, who had opened Pepe’s Dive Shop in Cabo Pulmo in 1992, was appointed director of the new park — with no salary and no staff. The nearest law enforcement was a three-hour boat ride away in La Paz, so Murietta, the Castro family and other residents continued to ask people fishing inside the park to leave. For the most part, says Francisco “Paco” Castro, they did.

In 1999, a research group including Octavio Aburto-Oropeza, then a university student in La Paz, assessed all Marine Protected Areas in the Gulf of California. Aburto-Oropeza, now a researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, says he didn’t find anything noteworthy about the Cabo Pulmo reef at that time.

A few years later though, the marine biologist started hearing about sightings of large animals there, especially big groupers. He returned in 2005. “I saw an amazing transformation, including huge schools of jacks and snappers,” he recalls. “The last day, we dove the most offshore part of the reef. A group of about 100 grunts were attacked and eaten by bigger fish. It was unbelievable, this huge surge of activity, all the fish swimming one way, fleeing, and then suddenly it was all over. You see this kind of event only in literature written back in the 1950s and ’60s.”

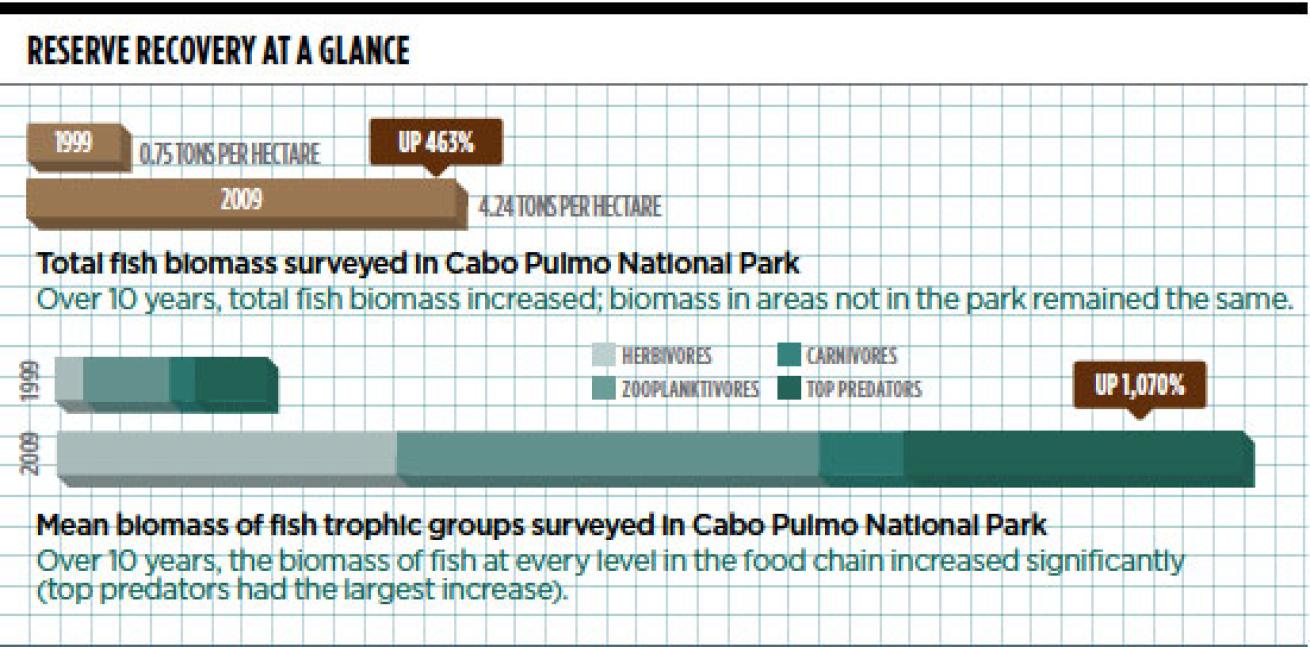

In 2009, Aburto-Oropeza repeated those 1999 surveys. The new data showed that reefs in Gulf of California’s protected areas hadn’t changed in terms of abundance and types of fish — except for Cabo Pulmo.

“We recorded an amazing change there,” the researcher says. “The most important changes were predators. Their biomass increased more than 1,000 percent, an unbelievably huge amount. An incredible positive transformation.”

The published study reports that from 1999 to 2009, total fish biomass in CPNP increased 463 percent, and density of fish recorded on the reef — 1.72 tons per acre — is some of the highest anywhere. The study also found the largest individuals for 25 of 88 species within CPNP. Researchers credit local enforcement with the stunning turnaround.

Diving in Cabo Pulmo offers great reward for little effort. A short walk from the dive shop, a row of white-with-blue-trim pangas waits on the beach. A stripped-down Bronco with a tire lashed to its rear bumper pushes a panga into the water, the driver fires up the engine and maneuvers around shallow reefs, heading from light- to dark-blue water. Divers do an easy backward roll off the side into the usually calm sea.

I made six dives here over three days in early May, swimming through enormous clouds of tiny, translucent fish larvae and tight schools of hundreds of red snapper, yellow snapper and jacks on every dive. I saw larger individual parrotfish, grouper and angelfish than I’ve seen anywhere. Each site sported numerous surgeonfish, damselfish, porcupinefish and triggerfish; I also saw an octopus, rays, eels and sea turtles. Depending on the season, it’s not uncommon to encounter dolphins, whales, sea lions, whale sharks and enormous schools of rays. Hard corals and sea fans cover long basaltic dykes running parallel to shore, mostly around 40 to 50 feet, allowing for long, leisurely dives.

Local tourism operations like the Castro family’s — along with two other dive shops — restaurants, and bungalow rentals generate roughly $18,000 annually per capita for Cabo Pulmo residents, more than the average in Mexico. Researchers and locals say this shows it’s possible to preserve the natural environment and still provide for the people.

Large-scale tourism developments — often put forth as alternatives for those who used to fish in the Gulf of California — bring new problems thanks to increased population, tourist-related fish feeding and human-nature interactions, the Scripps study points out.

“Our lives are better now,” says Judith, who has a young son, helps run several family businesses, and serves as president of Amigos para la Conservacion de Cabo Pulmo (Friends for the Conservation of Cabo Pulmo, or ACCP), originally founded to help protect sea turtles that nest in the area. “Change was hard,” she adds, “but we did the right thing. Now we know we can protect the ocean, and make a living from our natural resources.” Two years ago, members of the community, both Mexicans and ex-pats, joined with ACCP and other NGOs to form Cabo Pulmo Vivo in an effort to define the type of community its residents wanted. When I arrived, the group had just wrapped up two days of meetings, which were held in the open-air second floor of ACCP’s headquarters, a small concrete building painted with colorful fish next to the dive shop.

As I walked down the main dirt road toward a supper of fish tacos that first evening, Judith pulled up in her red pickup and handed me an executive summary of the brand-new strategic plan for tourism development in Cabo Pulmo. Its cover reads, “A sanctuary of sea, land and people; a truly ecological, rustic and authentic destination.”

“We want to be the best eco-tourism destination in Baja,” she says. That’s why her brothers Mario and Paco, and nephews Luis, David and Brian all work providing tourists with the chance to dive, snorkel, kayak, and otherwise enjoy the natural resources the family has worked so hard to preserve. The community’s leadership and stewardship has been key in the recovery of Cabo Pulmo, stresses Aburto-Oropeza, and is something that needs to be incorporated into the design of all MPAs. No-take areas account for less than 5 percent of other MPAs in Baja, and around the globe, only one-tenth of 1 percent of the ocean is completely protected from extractive activities such as fishing. Where protected areas do exist, they often suffer from poor management and limited enforcement.

But not Cabo Pulmo. “Jacques Cousteau called the Gulf of California the aquarium of the world,” Aburto-Oropeza says. “In many places, it isn’t any more. But when I dive Cabo Pulmo, I understand. It is like diving in an aquarium.”

NOTABLE DIVE SITES

El Bajo >> An excellent drift dive when the current is running — grouper, sergeant majors and schooling grunts congregate in large numbers.

La Esperanza>> Anything can happen here, from encountering game fish like tuna to getting wide-angle photo ops with huge amberjack.

El Islote >> This large rock promontory attracts schools of beefy jacks and several species of rays; tropical reef fish shelter in the reef’s stony corals.

Sea Lion Colony at La Lobera >> The rocks here are home to eagle rays and dozens of sea lions; the best time to visit is between January and October.