Ask DAN: Why Did I Get DCS?

Carlos and Allison EstapeWhy did I get DCS?

www.DAN.org/health

After finishing her second dive, Mia began to feel a strange sensation down her right arm. After her third dive the discomfort grew, but she thought it might be due to the new, heavy doubles she was diving with. The next day, extreme fatigue and numbness in her arm prompted a visit to the doctor. To her surprise, she was referred to a hyperbaric chamber. She met her deco obligations but didn’t understand how she could have gotten decompression sickness.

What is decompression sickness?

Ambient pressure increases during descent, causing the body’s tissue to take on more inert gas (i.e., nitrogen). A controlled ascent allows nitrogen to move from tissue and blood to the lungs where it can be exhaled. Decompression sickness (DCS) can occur when ambient pressure decreases faster than the elimination of nitrogen, leading to gas coming out of solution to form bubbles, much like when you shake up a soda bottle. The body can tolerate some gas bubbles, but if they enter sensitive tissues, a range of symptoms associated with DCS can occur.

It’s not about who deserves it

The DAN medical team often speaks with divers who, despite following their dive computers, developed DCS. Some divers consider these symptoms “undeserved” or “unexplained.”

Dive computers and tables are based on mathematical models that measure the pressure-time profile to predict the rate of on- or off-gassing for a given breathing gas. Allowable bottom times and, if necessary, decompression stops, are indicated based on the exposure. Although these models are useful in managing decompression risk, they do not account for myriad factors that can change that risk, for example when and how hard you exercise or your thermal state. Ultimately, your dive computer helps manage decompression risk but it cannot guarantee a risk-free dive.

How do I reduce my risk?

Exercise increases the body’s demand for oxygen. Subsequent vasodilation, or widening of blood vessels, increases blood flow, delivering more oxygen to the tissues that need it, and while diving, more nitrogen as well. Minimizing exercise intensity and avoiding overheating during the descent and bottom phase of a dive can reduce nitrogen on-gassing. Practicing excellent buoyancy control, proper hydration and getting adequate rest can also reduce risk. Finally, understand how your dive computer works: it is a tool designed to manage your risk — not the only means by which you measure it.

Evaluate your risk

Variations in body composition and function affect individual risk. Less physically fit and older divers may be at an increased risk. Some additional precautions are:

• Minimize on-gassing: Cut back your depth and time exposure. Consider diving with nitrox on air tables (or set your computer to air). Beware of the maximum operating depth of the nitrox mix.

• Maximize off-gassing: Avoid square-profile diving and practice multi-level diving instead. Add safety stops and appropriate surface intervals.

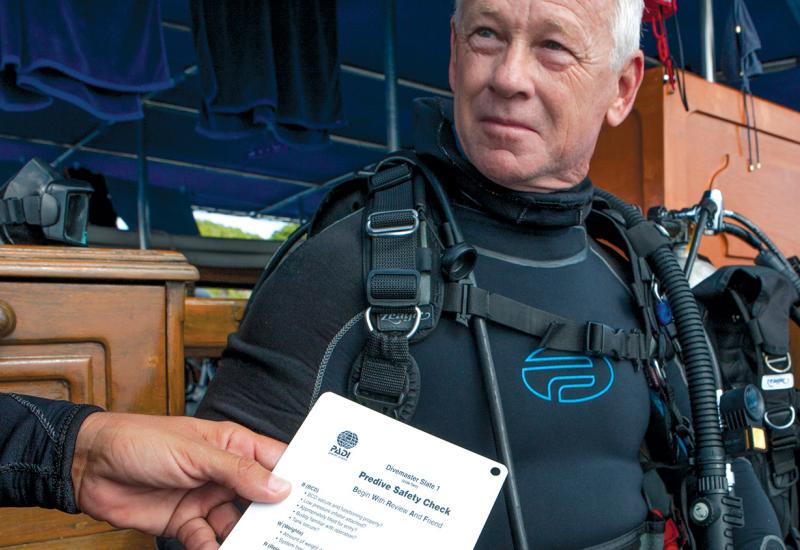

Be prepared

It is important to understand that no single element is the critical factor when it comes to DCS. A thoughtful diver will learn about potential risks and how to accommodate for them. Proper training can help you recognize and respond to symptoms if they do occur.

Learn more about DCS at DAN.org.