Four Sides of Bermuda

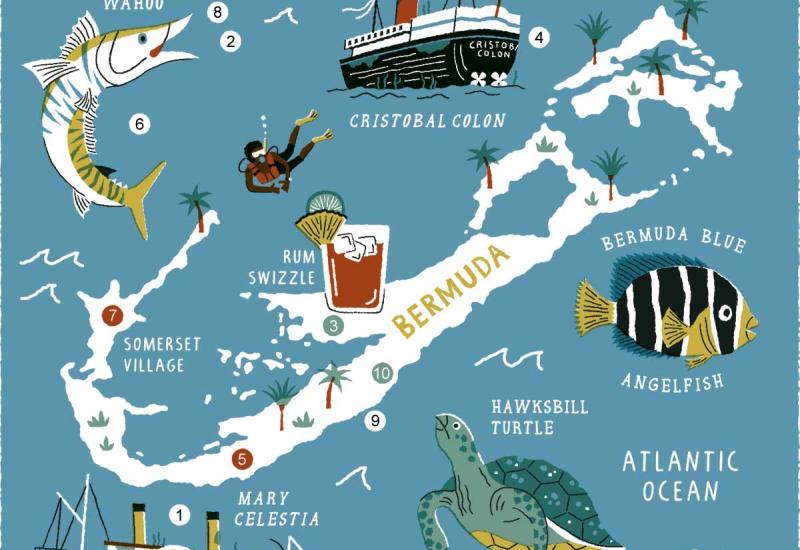

Bermuda. Once upon a time, in the bad old days, there were only two ways into this tiny archipelago 600 miles east of the North Carolina coast. Every other watery path was guarded by reefs that could ground or gore a ship, a virtual circle of hull-splitting monsters. On nights when the fog and the rain would allow it, lights marked the safe path into this mid-ocean refuge. On nights when those lights could not be seen or when false lights were put up by Bermudian "privateers" waiting for the next victim of the sea to come close to this seeming refuge was to tempt fate, to take a chance in a situation where the odds were all stacked against you.

Today, the only Jolly Rogers flying around Bermuda are on dive boats and T-shirts. Navigational channels are marked with radio beacons, and cruise ships thread their way into harbor using satellite navigation. There hasn't been a shipwreck in years. Plundering wayward vessels has given way to offshore business, re-insurance (insurance companies that insure insurance companies) and information technology as the preferred means of making a living. Afternoon might still be the time for high tea, but weekends and evenings can offer a panoply of activities, ranging from local kids dancing to performances by the latest hip-hop artists to Michael Douglas speaking at a film festival.

Still, some things never change. Despite all the navigational buoys and GPS signals, there are still only two natural channels leading to the harbors of this sophisticated little nation. And recently, when I paid a return visit to what has become one of my favorite wreck-diving destinations, I discovered that while Bermuda only offers two ways in, she was eager to show me four different sides.

SIDE ONE

It's the middle of the week, and the sun has long since set. High on the Bermudian ridge behind us, the bright, white beam of the Gibbs Hill Lighthouse is scribing its 40-mile sweep across the dark, empty Atlantic night. When I dip my head beneath the surface, I can see the dive light suspended on the end of our up line, swinging in the surge, piercing the black water, as if mimicking the 1,000-watt beacon up on the hill. I glance up at the swim platform and touch my fingertips to the crown of my head, giving the boat an "OK." "The wreck's dead ahead of us," says Michael Burke, owner of PADI Gold Palm 5-Star IDC Blue Water Divers. "Just duck under the boat and drop down. You can't miss it."

If Michael says the wreck is dead ahead, the wreck will be there. The owner of Bermuda's longest-running diving and water-sports center, he is one of those people who seem synonymous with Bermuda diving. Books on Bermuda shipwrecks almost always refer to him; most contain his photography. I nod and check my dive light. My dive buddy on this outing is Tom Farnquist, leader of the National Geographic expedition that retrieved the bell from the Edmund Fitzgerald and director of a prestigious shipwreck museum in the Midwest. We exchange thumbs-down signals, raise our inflator hoses and slip away into the blackness.

Dead ahead of us We're descending through the dark water in search of one of Bermuda's most famous shipwrecks, the Confederate blockade runner Mary Celestia. Tom and I are each wearing five additional pounds of lead Bermuda water contains far more salt than the typical Florida or Caribbean site but we still kick as we head down, wanting to find the bottom before the surge moves us around too much. In a minute, we see sand, shells, the odd sea cucumber. A minute after that, we spot the parallel lines of hull remnants poking up through the sand. These pass behind us, and we see more sand. Then more sand. Then more. Then a shape rises ahead of us. It's a coral-encrusted reef.

Well. That's not what we were looking for. We double back, looking for the hull remnants we'd seen earlier, and this time we don't even see that. Tom crooks a finger, makes a hull shape with his hands and then opens them: Where's the wreck? I shrug.

This is not good. The whole dive boat knows that Tom has discovered and dived an entire résumé full of virgin shipwrecks. And I've been telling war stories about my own wreck-diving experiences around the world. Our fellow divers have christened us "The Shipwreck Twins." If we can't find the wreck, the ride back to the dock is going to involve some serious image management. Finally, Tom describes a tic-tac-toe pattern on his palm, and I nod. We've been swimming north-south, so we turn 90 degrees and start going east-west. On our second pass, we run into the remnants of a paddle-wheel and beyond that a steam engine: the Mary Celestia in all her glory. A couple of other divers emerge from the blackness, their dive lights morphing from green to white as they draw nearer. They seem surprised to see us; we have obviously emerged from an empty quadrant. We busily explore the wreck, which has been lying on this bottom since 1864, and ignore the questions on our companions' faces.

Don't ask. Don't tell.

SIDE TWO

After a sound night's sleep, I'm just finishing breakfast at my hotel's buffet when the cell phone rings. It's Charlie Green, owner of PADI 5-Star dive center Dive Bermuda.

"The wind came up overnight and South Shore's pretty much blown out," he tells me. "So we won't be diving out of the Fairmont Southampton this morning. We're leaving out of Hamilton at 11:30."

I stifle a groan. Despite Bermudian laws that limit cars and trucks to one per household and prevent tourists from operating anything larger than a "bike" a motor scooter roads between Somerset and the business center of Hamilton tend to be busy with commuters until noon. As if reading my mind, Charlie asks, "Do you know Watford Bridge?"

"The ferry stop?"

"That's the one. I'll pick you up there at 12:30. Save you the run into town."

Sure enough, just a few minutes after the 12:15 ferry has left the concrete wharf, I can see Charlie's white dive boat bearing down on me from the far side of the Great Sound. As it gets nearer, I can pick out the first mate and the divemaster leaning from the bow pulpit, as if scouting for pods of porpoises or stray mines.

I grin. Charlie has known me for a while. Apparently, somewhere along the line, he has come to the erroneous conclusion that I am coordinated. He puts the boat upwind of me, throttles back, and as the breeze wafts the bow past me, I toss my gear bag and my camera across to the waiting crew.

Charlie repeats the maneuver and I make a committed four-foot stride from the wharf steps to the pulpit, clasp the rail like a gymnast mounting a pommel horse, and swing my legs over and inside, landing with my back to the flying bridge. The move apparently looks as dramatic as it feels because the entire dive boat applauds.

"Done the Constellation yet this trip?" Charlie calls down.

"I have," I tell him. "But I'd like to go back and see it again."

"There you go. I'll give you the Lartington for the second tank."

The divemaster, a pretty 22-year-old who began diving when her parents were missionaries in Papua New Guinea, has her hands full with a group of people working on their PADI Advanced Open Water certifications, so Charlie pairs me with Dan, a PADI Professional from Denver and a first-time visitor to Bermuda.

The two of us jump in and almost immediately spot the Constellation's pillowcase stacks of cement bags in the distance. But since I've been here before, I decide to take advantage of Bermuda wreck diving's two-for-one sale. I lead Dan south across a ridge of reef to the paddlewheel of the adjacent Montana, wrecked almost eight decades earlier than the Constellation, but on practically the same spot. The Montana's skeletal paddlewheel is usually a good photo op, so I raise the camera and press the shutter button, but apparently Dan is used to being photographed by divers using film, rather than digital cameras. In the fraction of a second between when I press the button and when the shutter moves, Dan is on the move. I take, and then delete, images of Dan's knees, Dan's fins, Dan's departing tank bottom, all beautifully exposed against backdrops of colorful, coral-decorated wreckage. Finally, I decide the guy's on a dive vacation here to have fun and not here to be my photo model so I chill out, turn the camera off and join him in the scenic tour.

Freed of the obligation to look at the dive through a viewfinder, I'm soon discovering marching legions of hermit crabs, their shells decorated with bits of sponge and coral. Tiny blennies freeze motionless on the 30-foot sand bottom, trusting their ability to blend with the surroundings. A juvenile puddingwife approaches within a few inches, turns her blue-scrawled face nose-on to me and somberly peers into my eyes. It feels like a special moment of silent, interspecies dialogue. But after a few seconds I deduce that she is contemplating her own comely reflection in the flat glass lens of my dive mask.

Dan and I cross the 50 feet of coral to the wreck of the Constellation, and bigger and better things begin to happen. A trumpetfish rises through soft corals, the upright posture of his body and his busy fins making me think of a flamenco guitarist rapidly strumming his instrument. When I peek into a square water tank, a grouper the size of a full-dress Harley swims out past me and retreats beneath a coral overhang. I approach for a closer look, and he booms at me, the sound uncannily like that of an angry pit bull on a very short leash. Meanwhile, all around us lies a virtual sunken Smithsonian of late-19th- and early-20th-century machinery. Long before I expect it, my dive computer beeps to let me know that we have reached the conclusion of our conservative 45-minute bottom time. We head up to our safety stops and the surface, better than half the air that we started with still in our tanks.

On our next dive, the Lartington, Dan more than makes up for his shortcomings as a photo model. I am swimming past the boilers when he begins to rapidly shake his underwater rattle. I turn and he is pointing earnestly into the open top of an ancient steam-condenser tank, once part of the Lartington's propulsion system.

Lobster, I think as I swim his way. But when I peer into the tank, there on the overhead, his plumage raised in full intruder-alert display, is a large adult lionfish.

I'd heard about this. Lionfish, a venomous species native to the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, have been reported in Bermudian waters for better than two years now, but this is the first time I've actually seen one. He is magnificent: The diaphanous fins along his spine are dotted with fine brown markings, and the nearer I get, the higher he raises his broad, turkey-feather-like hackles. There are two theories as to how lionfish arrived in Bermuda. The first, forwarded by many dive operators, is that eggs or tiny hatchlings were drawn in along with ballast water by fast cargo ships leaving the Pacific, and then discharged along with that water on their arrival in Bermuda. Another, embraced by many biologists, is that Bermuda lionfish are the descendents of aquarium fish released along the East Coast of the United States lionfish are now frequently reported, for instance, along the Outer Banks and then swept farther and farther eastward by the seasonal west-to-east migration of the Gulf Stream. Either way, they are now strangers in a strange land, an invasive species with no natural enemies.

Environmentally, this concerns me. But aesthetically I am fascinated. This is one beautiful creature. Like all lionfish, the one in the tank has turned tail-first toward the perceived threat me and if I'm going get a picture to show the folks back home, I want to see his face. So I crawl into the close space of the tank along with him. Dan, meanwhile, is hovering behind me, no doubt conserving his air so he can haul my convulsing, unbreathing body back to the dive boat after the angry lionfish stings the living daylights out of me. A sergeant major guarding an egg mass on the back of the tank apparently decides three creatures in this little iron tank is one too many. He pulses dark blue and darts at the lionfish, which first nips at him and then aims his dorsal spines at his attacker. It's a happy accident, and I get my snapshot without having to send out for antivenin.

SIDE THREE

For so diminutive a country, Bermuda is surprisingly diverse. The middle-class people of Somerset view city dwellers in Hamilton with the cool sort of distance that farmers usually reserve for office workers. And some parts of the country, like St. David's Island, are seen by Bermudians from elsewhere as virtually a separate country. So when I travel from Somerset on the West End to Grotto Bay on the East, the trip may take less than an hour by taxi, but culturally, it feels like we're crossing time zones. "Tom! It's great to see you, man!"

Graham Maddocks, owner of PIRA member Triangle Diving, wraps his arms around me and gives me a rib-flexing hug. It feels as if I've just gotten home from a trip abroad, which in a way I have. I was here a year earlier, diving with Graham as I researched a novel set in Bermuda, and Graham, a keen wreck hunter and self-taught historian, embraced my project as his own, looking up facts and sleuthing out odd bits of trivia. He, his brother-in-law Ken and I have stayed in touch, sometimes exchanging several e-mails and phone calls a week, and when Graham says, "It's like you never left!" I have to agree.

For Graham, scuba charters are a labor of love. During the cruise-ship season, he also operates a helmet-diving business that allows visiting nondivers to walk about on the seafloor in 12 feet of water, using surface-supplied air. The boat he uses is huge, a drug runner seized by the DEA, which actually has patched machine-gun holes showing beneath the waterline. But his dive boat is a more intimate affair, tailored toward the smaller parties that he caters to, and his dive operation, based on the water at the Grotto Bay Beach Resort, easily reaches all of Bermuda's East End wrecks, with the north and the south reefs both within easy running distance.

As we slowly rumble out of Grotto Bay and past the historic town of St. George, Graham keeps up a running commentary, pointing out a Russian freighter that sank at her dock in 1896, and another wreck that burned to the waterline and settled where she was moored. As St. David's comes up on our starboard bow, he shows us the lighthouse that Robert Shaw supposedly lived under in the motion picture The Deep, and several divers wonder aloud how it is that it still has its top (a full-scale replica long since removed was constructed on Bermuda's North Shore, and its upper portion was dynamited in one of the movie's more spectacular special effects). As we exit St. George's Channel and enter Gunner Bay, Graham slows so we can look at Fort Cunningham, built in 1612 and manned for more than two centuries, and Fort Popple, dug into the Bermuda-stone bedrock in 1638. He talks about their construction, and while Graham is young an athletic 39 his voice takes on a wizened, sentimental tone as he describes his country's history. I begin to wonder if he might not have served in one of these stone forts in a past life, looking out on a vista that is solid salt water from here to the Canary Islands.

Snow-white longtails, the birds that are the national symbol of Bermuda, wheel over the dive boat and swoop low over the cliffs on the shore. This end of Bermuda is almost like a little country in its own right, the buildings fewer and older, the shores more obviously storm-blasted. On Graham's larger boat, four divers can enter the water at once two from the swim platform and two through the step-throughs on either side and when he gives us the all-clear, we empty the vessel like lemmings.

As soon as the bubbles clear, a scene of decades-old devastation unfolds beneath us. The Rita Zovetta, which ran aground here in bad weather back in 1924, has been pounded by 82 years of storms and is now strewn over the rocks, but her hull bridges two reef sections, creating a dark, grouper-haunted grotto. Her steam engine still stands in full Smithsonian glory, and the entire site is dotted with swim-throughs, perfect for games of diver follow-the-leader. Because it's possible to get as deep as 70 feet on this dive, Graham has recommended a bottom time of 45 minutes, and my timer beeps all too soon; with all its nooks and crannies, the Zovetta is one of those wrecks you can dive several times and still not see everything.

We ask to stay in the area for the second dive, and Graham complies, taking us to the Pelinaion, which sank right next door in 1940. But before that, he takes us past King's Castle, the fort involved in Bermuda's one and only sea battle with Spain. A Spanish ship of the line once tried to make a run past the fort into Castle Harbour and was greeted with two shots, one of them through her rigging. Her captain retreated, not knowing that his English welcoming committee had only one cannonball left, and that in their haste to reload, they'd overturned their only powder keg to boot.

SIDE FOUR

Hamilton, the country's business center, is Bermuda with a briefcase. My taxi makes good time, so I kill a few minutes at the Hamilton Princess hotel, grabbing a skim latte from the coffee shop on the main floor and admiring the famous Desmond Fountain sculpture of Mark Twain on a bench in the lobby. Then I make my way up the street and down to the waterfront. "Welcome to the Bermuda IV."

"Holy smokes."

I can't help myself. I'm accustomed to being greeted by boat crews, but this is the first time that a full crew captain, director of diving operations, cook and stewardess has turned out on the dock in dress uniforms (complete with epaulets) to welcome me aboard. I shake hands and turn to grab my luggage, but it's gone, already on its way to my stateroom in the broad stern of the 94-foot custom Hargrave yacht. I take one look at the spotless decking on the handsome green-hulled vessel and remove my shoes before stepping board. Except for dive booties, which I'll don next to my locker on the swim deck, I will travel sans shoes for the next several days, and I will also be neck-deep in opulence. My master stateroom is considerably larger than the room they gave me the last time I stayed at the Waldorf Astoria (I have two walk-in closets, a shower with tub, and a queen-size bed that I can enter from either side), and I haven't even taken a seat before Aaron, the cook, is asking if I've had breakfast. I have, but I accept his offer of coffee, which arrives in china, with matching sugar bowl and creamer, and a freshly baked muffin just in case I've developed an appetite in the past five minutes.

By the time I've put a few things away in my cabin, the crew has changed into working uniforms (matching polo shirts and Bermuda shorts), and we are underway, smoothly making our way into the Great Sound. I go up to the flying bridge to chat with Captain Mike Davis and comment on how solid the vessel feels. "We work on that," he tells me. "Our clients don't like the boat to move."

I ask him what dives he has in store for me, and he counters by asking what I would like.

"Well," I venture. "I haven't done the Cristobol Colon yet on this trip." I glance at the Bermuda IV's bow pennant, snapping fiercely in a quartering wind. "Of course, the wind's probably a bit brisk for a trip that far offshore."

"It's almost ten miles," Mike agrees. "And the wind is a bit fresh. But we'll never know until we try, will we?"

As we leave the sound, the ocean seems to be sending us Morse code, dotted and dashed to the horizon with whitecaps. Yet the big vessel is still steady; my coffee cup doesn't budge an inch on the bridge table. We are pulling a small rigid-hull inflatable tender with a center console and outboard, and I assume that we'll stand off and use the tender to get to the dive site (there's a reason the Colon sank where she did; the area is virtually carpeted with reefs). But with GPS guidance and the crew spotting via radio from the bow, Mike is able to thread the yacht so close that I can look into the water and see the sunken cruise ship's boilers. We anchor in a sand patch (especially with the greater scope required by the wind conditions, the Bermuda IV is too long to use the regular mooring on this site).

I'll later learn that Mike, a Bermudian who first learned to sail in these waters and who is still a member of the Bermuda Regiment, comes by his knowledge of the reefs the same way he knows the history of the beaches and houses we'll later pass on the shore through long experience. Although he has been to and from the Island (as Bermudians call their country) many times over the years to go away to school, to serve in the Army, and most recently for seven years as CIO of a New Jersey company it's clear that he considers these 20.5 mid-Atlantic square miles his home.

Deep by Bermudian standards at 60 to 80 feet, the Cristobol Colon wrecked as a result of running fast aground in 1936, but technically it did not sink until several years later when the U.S. Army Air Corps used the hulk as a target for bombing practice. She now rests on either side of the reef that claimed her, her stern still standing and covered with plate coral, her propulsion system still visible and enigmatic (visiting engineers have said that it appears the Colon's crew would have had to perform minor surgery to coax the ship into reverse quite possibly a contributing factor in her stranding).

Lionfish rumored to inhabit the Colon's stern fail to put in an appearance, although a loggerhead sea turtle peeks out of a niche in the boiler, as if wondering what all the noisy bubbles are about. Christine East, the Bermuda IV's director of diving operations, is competent and cheerful underwater company, and as she is both a PADI Specialty Instructor and a former Cathy Church staffer, she's a positive asset to any dive outing.

It's one thing to get out on the reef in conditions that have kept most other dive boats close to shore. It's another to do that and come back into harbor for a meal of lamb cutlets served with fresh Bermuda mint, presented in a fashion that leaves you wondering whether to pick up your napkin or your camera. And after dinner, as the sun descends and the long yacht slowly swings at anchor, it's surreally pleasant to discuss history, books and cinema in the open-air salon while a thousand tree frogs sing serenades in the starry background.

Leaning back, I hum with satisfaction. Bermuda has many sides, but one thing is certain. No matter which way I look at it, the Island gives me reason after reason to return.

Special thanks to the Bermuda Department of Tourism (bermudatourism.com), the Bermuda Maritime Museum (bmm.bm), the Bermuda Underwater Exploration Institute (buei.org), Blue Water Divers and Watersports Centre (dive bermuda.com), Dive Bermuda (bermudascuba .com), Grotto Bay Beach Resort (grottobay.com), Nine Beaches Bermuda Resort (9beaches.com), Triangle Diving (trianglediving.com), The Royal Gazette (theroyalgazette.com), Dr. Ed Harris, Mr. & Mrs. Teddy Tucker, and the generous and friendly people of Bermuda for their insights, their assistance and their support.