A Conversation With Underwater Artist Jason deCaires Taylor

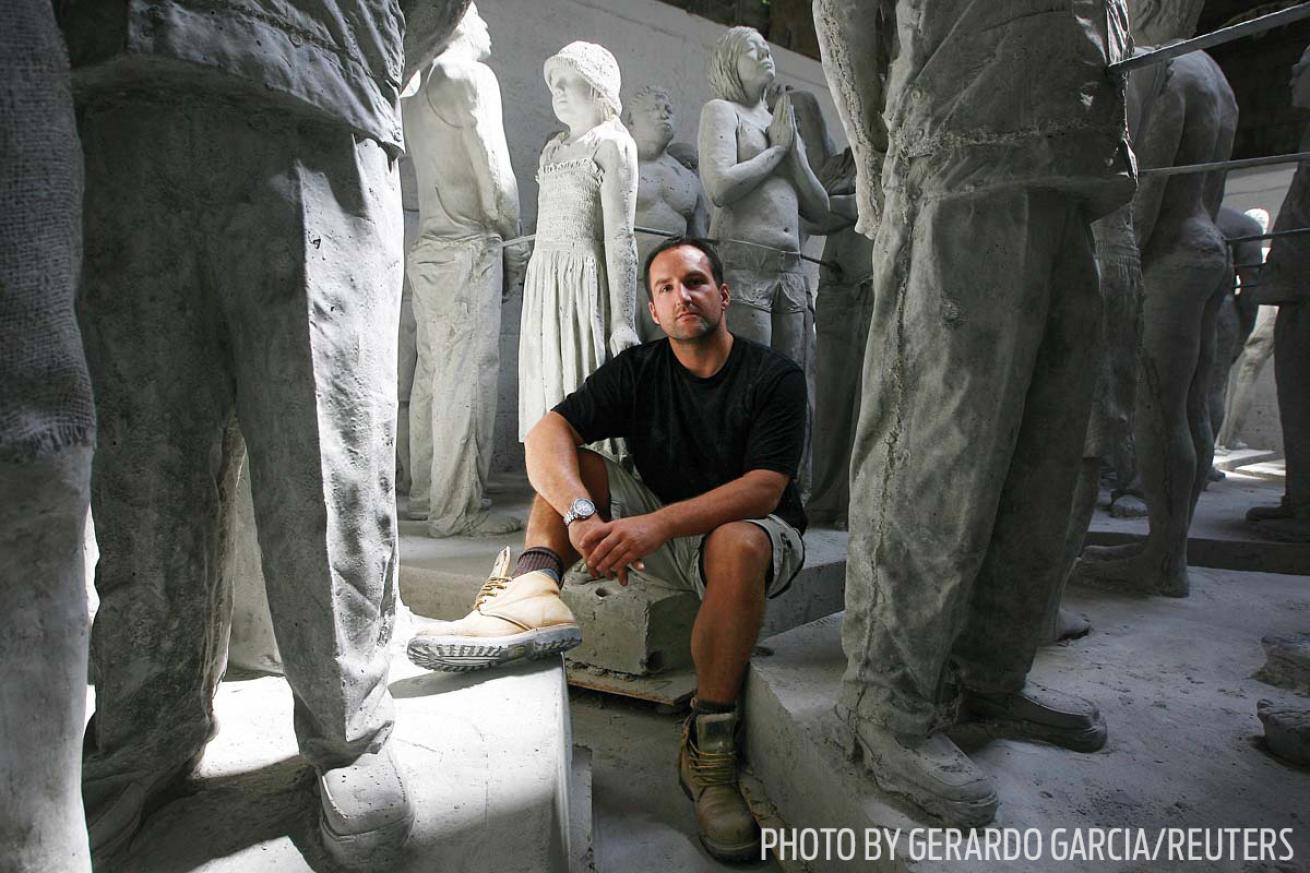

Gerardo Garcia/ReutersUnderwater artist Jason deCaires Taylor

Sculpting is the easy part, says British artist Jason deCaires Taylor of his cement life-size-and-larger figures placed underwater. It’s sinking the pieces, some weighing as much as 60 tons, that complicates matters — he was once nearly crushed in the process. But for the most part, these works, which he’s been creating since 2006, have been a success, placed worldwide from the Thames River in London to Mexico’s Cancun coast.

Q: What would readers be surprised to learn about your process?

Taylor: Generally, my works are figurative. They’re reflections on ourselves, so I have models come to my studio. They undress, get covered in Vaseline and paste, and I make casts.

Q: And what about sinking the pieces?

JT: It’s a Catch-22: You want the objects as heavy as possible to stay rooted to the seafloor, but if they’re too heavy, transportation to the site is tricky.

Q: How so? I saw a photo of a diver riding alongside a piece lowered by crane. Was this you?

JT: I’m not always sitting on the sculptures. Sometimes we tow the really heavy pieces. One of the new pieces in Lanzarote weighs 10 tons. We sank it with a crane, floated it with lift bags, and then towed it to the site. When you tow objects in the sea, things can get problematic. Tides, waves, weather — friction cuts ropes. I have had lift bags rip and sculptures almost sink on top of me in Cancun, Mexico.

Jason deCaires TaylorThe Raft of Lampedusa is one of the featured pieces in Museo Atlantico off Lanzarote, Spain.

Q: What saved you?

JT: I was lucky. The sinking piece missed me by a foot. If I had been slightly out of place ...

Q: Wow. A lot goes into your underwater galleries. How can visitors make the most of a visit?

JT: I really like night dives. You focus on small patches where your torch shines, as opposed to trying to take in the whole lot.

Q: What has been your most memorable night dive at one of your underwater galleries?

JT: Off Cancun, during a full moon, I turned off my torch and saw silhouettes of the figures. It was like walking through a forest at night. I could just make out the shapes — it was otherworldly.

Q: I’ve heard you appreciate fire coral. Tell me this isn’t true.

JT: It’s very invasive, as you know. With it, I’m able to paint sculptures, like Man on Fire, in gold. You can propagate it to engulf a piece. Fire coral’s Latin name is Millepora, which means 1,000 pores, so up close, it looks like human skin with its tiny hairs. It makes the pieces appear even more alive, so, yeah, I am a fan. Fire coral is also great because people don’t hug my sculptures or take selfies.

Q: Tell me about the message behind the piece Selfies, a sculpture of figures taking pictures of themselves.

JT: I see this too often when I go diving — people going down with so many cameras. They’re watching every moment through a camera display, not appreciating the actual experience.

Q: And what about the piece Rubicon, a collection of 40 figures, walking zombielike across the sand. What’s the message?

JT: A Rubicon is a point of no return. A line that once you cross, you can’t turn back. The piece is about how much loss we’re sustaining from our oceans. We can’t bring back the bluefin tuna and the incredible reefs. The piece symbolizes how we are advancing toward this loss without working coherently together to stop it.

Deep-Blue Debut

Taylor unveiled the first underwater contemporary-art museum in Europe and the Atlantic Ocean in February: Museo Atlantico. The museum — located off the coast of Lanzarote, one of Spain’s Canary Islands — is in 45 feet of water, giving novice divers and snorkelers the chance to see Taylor’s sculptures. One of the featured pieces, The Raft of Lampedusa (above), is a reference to Théodore Géricault’s 1818 painting The Raft of the Medusa, and a depiction of the worldwide refugee crisis.

Check out deCaires Taylor's Ocean Atlas piece in the Bahamas and our 50 Ways to Play Underwater.