An Inside Look at the Process of Discovering New Species of Nudibranchs

An inside look at the process of discovering a new species of nudibranchs, something that researchers and recreational scuba divers can do thanks to thousands of undiscovered species in the ocean.

Christian SkaugeThe beautiful Cumanotus beaumonti nudibranch in the waters of Norway

Twenty feet below the surface of the swirling clear waters — a short ride off the coast of the Philippines’ Mindanao island — a small, 3- to 4-inch luminous creature crawls into the divers’ view. It’s a peculiar-looking nudibranch, a tiny marine gastropod, whose soft pink glow shines through the water much like the area’s surrounding coral.

That’s when the tiny animal caught the eye of Terry Gosliner, a nudibranch discoverer, and Jerry Allen, an underwater photographer, who had taken a boat ride out to a scarcely explored patch of water. Allen was busy capturing shots of a vibrantly decorated mandarinfish as the sea slug inched slowly, but suddenly, out of obscurity and into the pair’s frame of view.

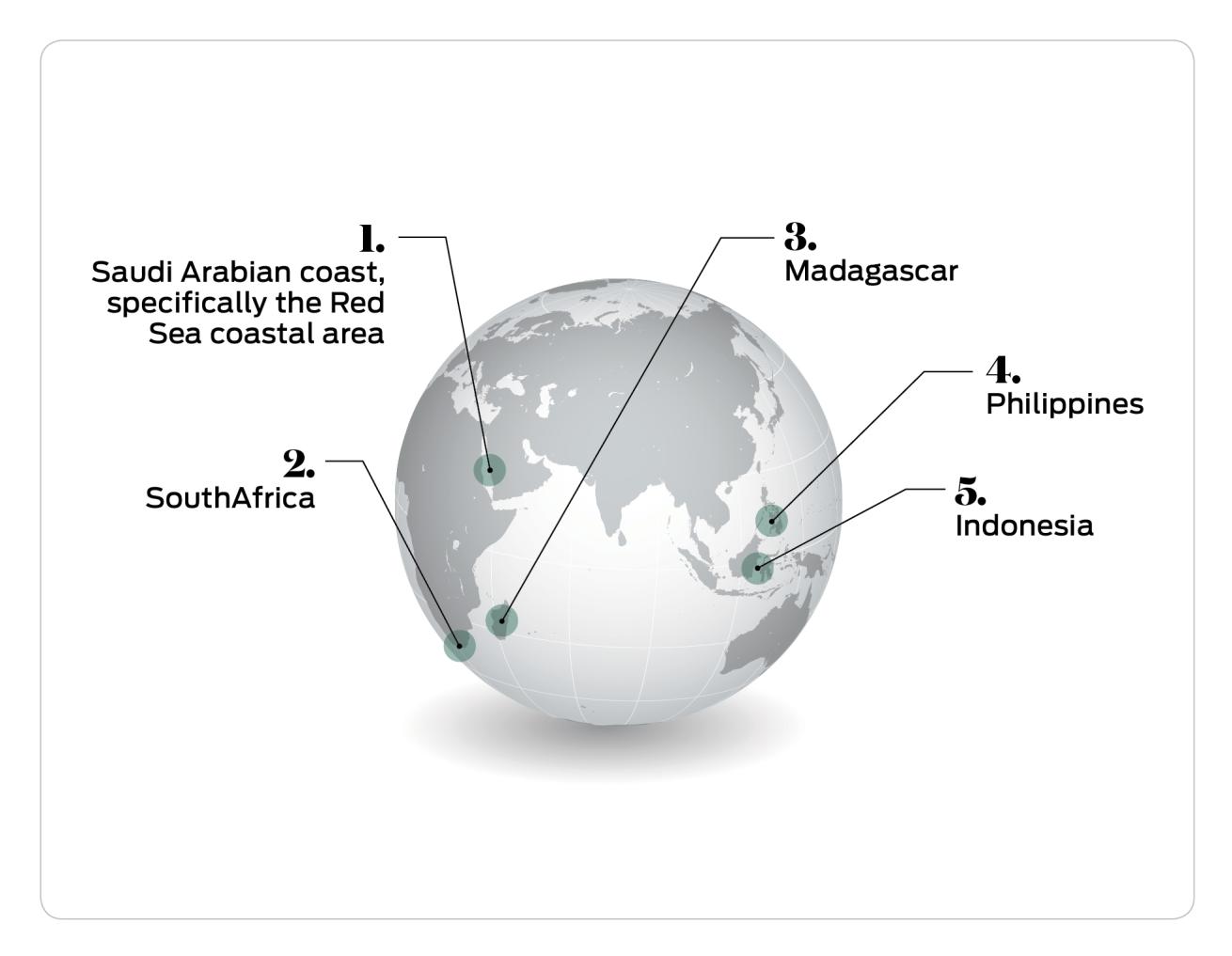

Sport Diver EditorsThe largest diversities of nudibranch species are typically found in tropical waters. They can be found in cold, deeper waters too but are more prone to warmer, shallow areas. The environments with the most robust populations tend to be dense with substrates, such as corals, which provide a habitat and food source for the nudibranch.

Allen and Gosliner shifted their attention from the mandarinfish to the tiny creature. Allen snapped a flurry of photos while Gosliner gazed at its cryptic color and pattern.

Gosliner suspected it to be a new species, captured the specimen, placed it in an alcohol-filled glass container for preservation, and took it back to the lab for testing. Much to his delight, his supposition turned out to be correct: It was a never-before-documented species.

Such is the process of discovering new nudibranchs, the tiny sea slugs that range in length from one-tenth to 10 inches. While many people prefer chasing encounters with large marine animals like sharks, searching for nudibranchs has become a beloved past time for recreational divers and scientists alike who gawk at their vibrant colors and diversity. An abundance of species is also a reason for this: There are more than 2,000 documented nudibranch species, and some scientists estimate that there are just as many yet to be discovered.

That’s a green light for divers with a penchant for discovery.

And while the process of searching for new species is usually one that’s complex and planned in advance, Gosliner shows that even for a scientist it can sometimes occur by chance.

“It was one of those things that was totally accidental,” he says. “Species can be found in the most surprising places.”

Christian SkaugeDivers study specimens at Gulen Dive Resort in Norway.

Gosliner’s experience discovering nudibranchs dates back to his high school days growing up near the coast in Marin County, California, where he would go out tidepooling with friends. That’s where he found his first new species as a senior in high school — on a day he was supposed to be at graduation practice.

From there, he went on to study marine life at several universities and has since become a leading expert in nudibranch discovery, having found roughly 1,500 species — with about 400 officially named so far. Gosliner currently serves as the curator of invertebrate zoology and geology at the California Academy of Sciences, where he spends his days planning dive trips to search for undiscovered species across the globe.

The discovery and identification of new species can be a long, formal process, Gosliner admits. It typically begins with scientists planning research trips to new or scarcely explored dive spots. Once on location, researchers dive into the water at varying depths. Large amounts of diversity tend to exist closer to the surface, where ample sunlight allows for an abundance of sealife to flourish. Gosliner usually focuses his search there and dives down to no more than 130 feet.

Having memorized many of the species, Gosliner, like most experienced nudibranch researchers, tends to spot new species just by looking at their distinct colors and patterns — such as with the glowing pink nudibranch. If scientists do think they have spotted a new species, they start by photographing it in the water to document it in its natural habitat. They then take notes of its behavior, ecology and every available detail.

Christian SkaugeA researcher takes a closer look for identification.

If it still seems to be a new species, researchers will capture one or more of the tiny specimens to be preserved in a glass container with alcohol. At least one of the organisms will then be shipped back to a lab for dissection and DNA sequencing to map out its identity. That’s what Gosliner ended up doing with the coral-colored slug.

“After that initial discovery, we found it in several different places in the Philippines,” Gosliner says. “It’s a reasonably common species, once you know what to look for.”

The last step in the official discovery process is having the species documented in the scientific literature. That entails detailing in writing the species’ anatomy, DNA and ecology, and outlining what makes it different from others. That then goes through publication and peer review. In all, the process can take years.

Gosliner says it’s important to note, however, that it’s not just scientists who can do the discovering of new nudibranchs, but interested and knowledgeable everyday people too.

Christian Skauge, an experienced underwater photographer, knows that well. Skauge hosts an annual Nudibranch Safari at the house reef at Gulen Dive Resort, on the western coast of Norway, where large groups of interested divers, photographers and scientists gather to venture into the icy water in an attempt to find as many nudibranch species as possible.

Citizen Science

You don’t have to be a professional to spot a new nudibranch species. But there are steps you can take to increase your odds. First, since the animals tend to be small in size, it’s best to swim slowly and stop periodically to look for any slight movement of bright colors climbing on coral or rocks. “Any place a lot of people haven’t been to can have a wealth of different species,” Gosliner says. Once an organism is found, it’s best to photograph it and its environment. Scientists can usually tell on-site if it’s a new species, but everyday explorers can catalog their find through photos and compare it with others online. Official discovery includes taking a sample specimen, cataloging its DNA, and going through an extensive scientific review process that can take several years.

At the safari — which has already uncovered more than a dozen new Norwegian nudibranch species — photography, rather than science, is key. “You take pictures of everything you see,” Skauge says. Since not all safari-goers are scientists, photography proves the best way to identify a potential new species by documenting it, its food sources and surrounding habitat. That documentation can be published online, or sent to a scientist for further study.

“We have the stereoscopes and the literature to look at them, compare them, and read through to try to piece together what it might be,” continues Skauge. “If we can’t do it with a degree of certainty, then the scientist must say, ‘OK, maybe we should have a closer look at that one.’”

Skauge made a particularly interesting discovery one winter several years back while diving in the waters of the house reef. He and another diver were about 75 feet below the surface when they started to see unusually large, orange-colored nudibranchs swimming out into the open water.

After photographing the sea slugs, Skauge conducted research and suspected the nudibranchs to be of the Berghia norvegica species, which was first described in 1939 and never seen since. Skauge and his fellow diver tracked down the nudibranchs again the following year.

They captured a specimen and sent it off to a scientist for testing, which confirmed his suspicion. Finding such a rare species that hadn’t been seen in decades was fulfilling, Skauge says, because it’s exactly that kind of excitement and intrigue that draws people to nudibranch exploration in the first place.

“It inspires a lot of people,” says Skauge of making a discovery that benefits science. “I think more people have walked on the moon than have seen that nudibranch in the ocean.”