What Is Killing Leopard Sharks in California?

iStockNecropsies have been performed on 26 leopard sharks that died in the waters off northern California.

If you’re a fan of Law & Order, you know Dr. Elizabeth Rodgers and Dr. Melinda Warner, the medical examiners in the fictional universe of the crime drama franchise (played by Leslie Hendrix and Tamara Tunie, respectively). Law & Order episodes are aired in two parts; the first part follows the police and detective work, including a brief scene in which the M.E.s provided the detectives with forensic evidence to support their cases.

If only forensics in real life could be so straightforward and fast. In animal autopsy — called necropsy — the work of the pathologist can be painstakingly slow and leave the scientists with more questions than answers.

Pathologists have completed necropsies on several of the dozens of leopard sharks found dead in San Francisco, but can’t definitively pinpoint the cause of the sudden die-off. Leopard sharks continue to be found dead or dying on beaches in Foster City, Hayward, San Francisco, Berkeley, and other sites. The recent die-off has probably killed as many as 1,000 since early March, experts say.

Mark Okihiro, a California Department of Fish and Game senior fish pathologist, found “inflammation, bleeding, and lesions in the brain, and hemorrhaging from the skin near vents” in some of the sharks. Bleeding was also detected around a female shark’s internal organs. Okihiro usually works to examine disease in white seabass hatcheries. But recently he has become an expert on what causes sharks to die. So when the leopard sharks were found either dead or dying, Okihiro was asked to perform necropsies on 26 of them.

Leopard sharks, which can grow up to 5 feet long, are the most abundant sharks in San Francisco Bay, and are found from Oregon to Mexico. Although they are not endangered, the sharks are a key part of the food chain in the bay, eating clams, worms, crabs and small fish, in relatively shallow water.

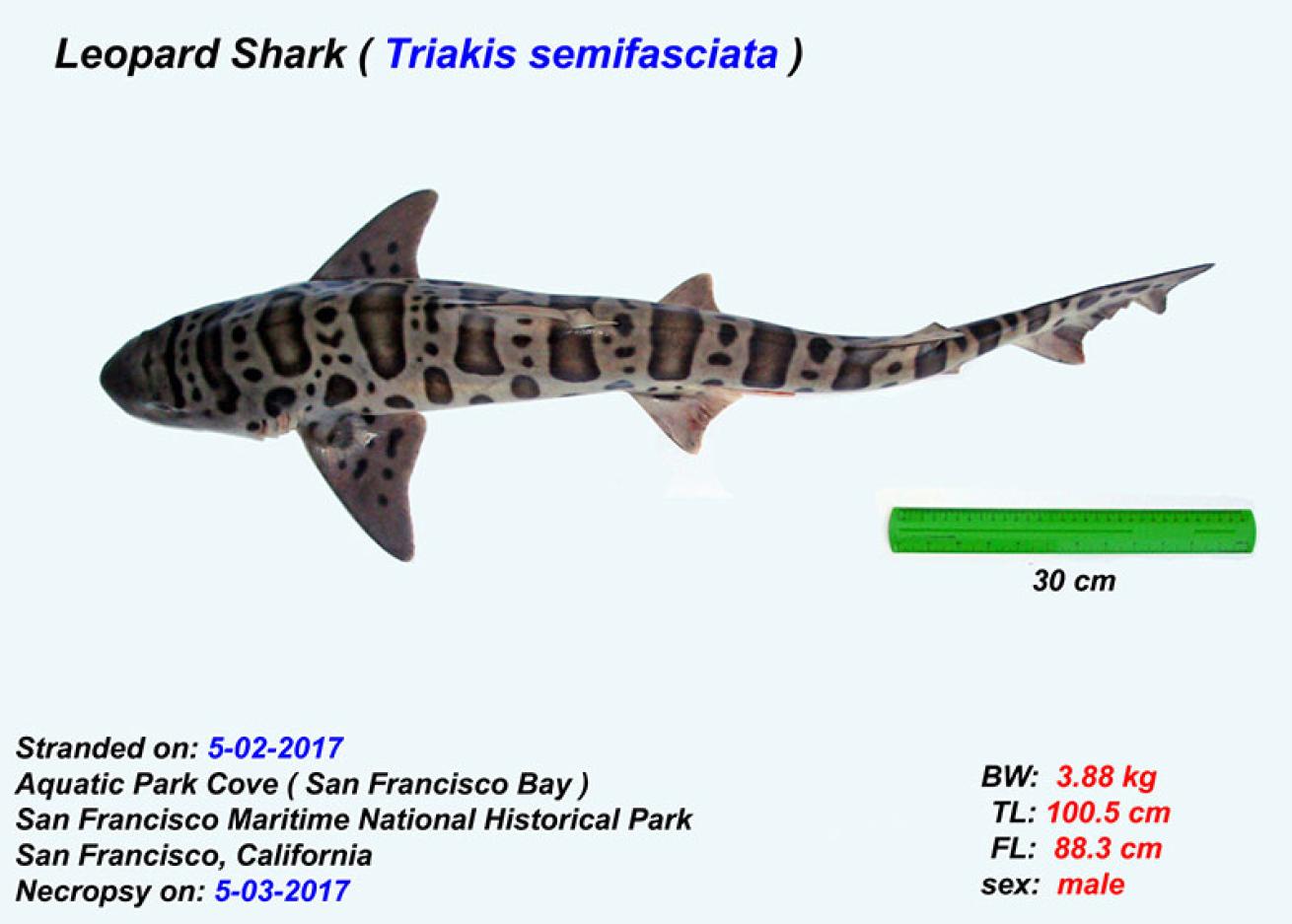

Courtesy California Department of Fish and GameOne of the leopard sharks Okihiro performed a necropsy on.

“They are apex predators. If you pull them out of the ecosystem, it’s obviously going to have a pretty big impact,” Okihiro told The Mercury News.

Okihiro has found a fungus that appears to have invaded the sharks’ bodies through their noses and ducts in their heads, indicating that they may be dying from some type of fungal meningitis.

But much is still unknown.

The Pelagic Shark Research Foundation has been providing updates on its Facebook page, and noted that as in previous years, where “mass strandings and die-offs have struck during spring and early part of summer, the 2017 SF Bay pupping season has been devastated for the second year in a row.”

Okihiro and his colleagues believe that the sharks died from a ciliated protozoa (Miamiensis avidus) that were present in the brains of some of the sharks. This is known to be a rapidly lethal systemic infection in sharks kept in aquariums.

"Although Miamiensis avidus is histologically the most destructive pathogen present in the brains of dying leopard sharks, it is by no means the only pathogen involved with shark strandings," says Okihiro. "No Miamiensis protozoa have been observed in the samples taken from seven of the stranded sharks. Instead, cerebrospinal fluid was dominated by a wide variety of pleomorphic cell types, along with bizarre cellular aggregates, some with pseudopodia or psueudohyphae."

Courtesy California Department of Fish and GameFor reasons researchers don’t understand, sometimes bacteria become pathogenic, and then enters a shark via its ears or nose.

That can sound like a lot of scientific mumbo-jumbo to the lay person, and there are a great many unanswered questions, including whether the sharks' preferred habitat played a role.

“There are thousands of fungal species out there in the water and soil,” he said. “It might be very common — and just that these leopard sharks are in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Okihiro is "having trouble distinguishing between possible/probable fungal hyphae and remnants of degenerating neuronal axons/dendrites in nerve tracts that have been severely damaged. The other big caveat is that there has been little consistency, thus far, with the metagenomic assessment of CSF, the histology, and the culture results. Metagenomic results initially came back as 'uncultured soil fungus' and we are working with UC San Francisco to try and refine those findings."

Okihiro is hoping to definitively show that fungus play a major or minor role in damage to the olfactory bulbs and lobes of the brain of the sharks. "I will also need to submit additional histology samples from other stranded sharks (to help define the roles of both protozoa and fungi in meningitis and encephalitis."

Okihiro plans to consult with marine planktonologists at Scripps Institute of Oceanography to obtain more information.