NOAA discovers WWII vessels off coast of North Carolina

After six years of research, a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has identified two Word War II vessels, which until now lay unnamed at the bottom of the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

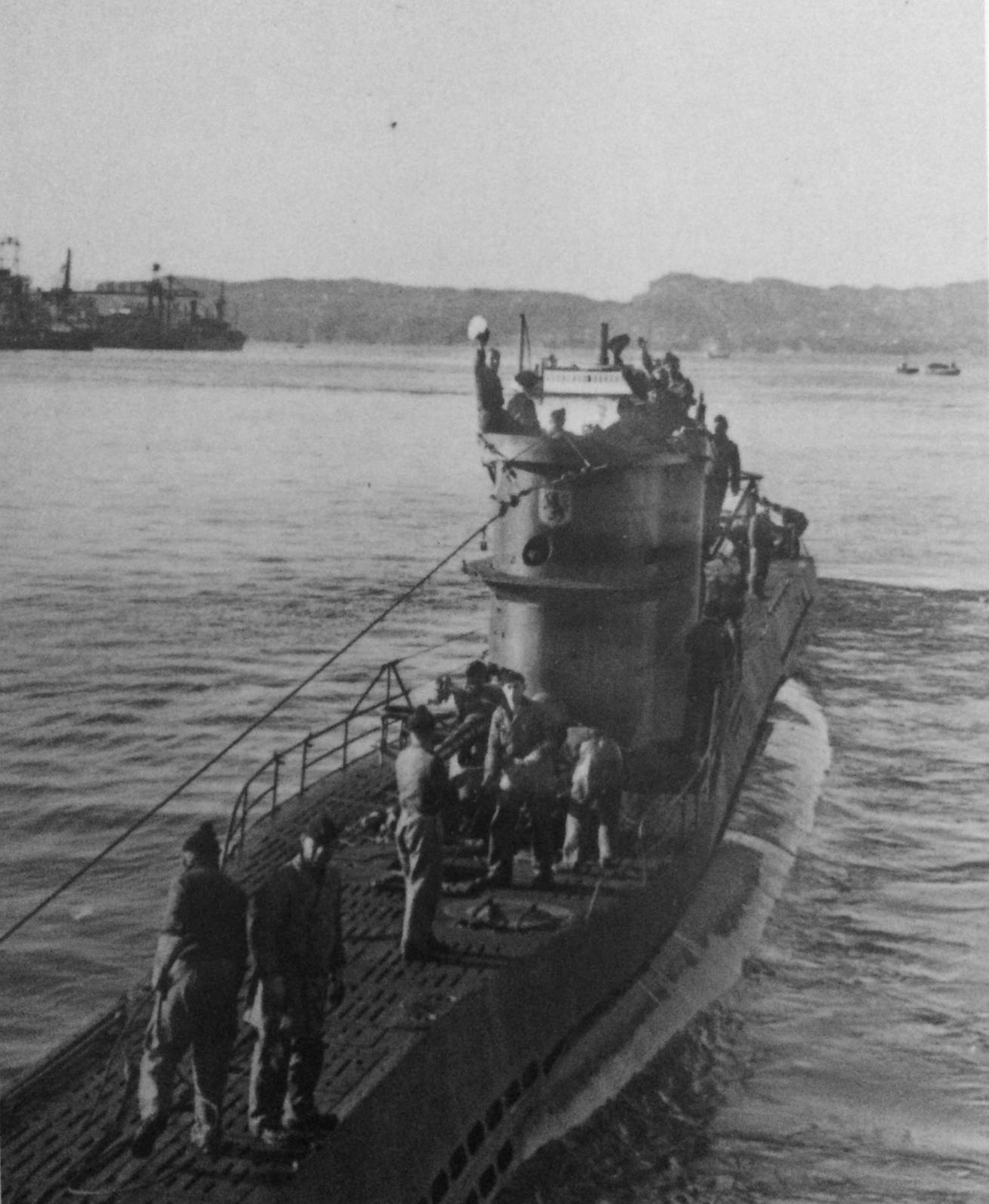

Lost for more than 70 years, the vessels — the German U-boat 576 and the freighter Bluefields — offer a peak into the window of the little-known underwater battlefield 30 miles off the coast of North Carolina.

First discovered back in 2008, according to the NOAA, U-576 and Bluefields lie on the seabed less than 240 yards apart. Joe Hoyt, a Monitor National Marine Sanctuary Maritime Archaeologist who served as the principal investigator on the project, hopes the milestone will help researchers piece together the forgotten stories of vessels’ demise.

On July 15, 1942, as part of Convoy KS-520 — a group of 19 merchant ships escorted by the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard — the Nicaraguan-flagged Bluefields was en route to Key West, Florida, from, Norfolk, Virginia. Near Cape Hatteras, the convoy was attacked by German forces, which led to the sinking of Bluefields at the hands of U-576. The U.S. Navy Kingfisher aircraft responded by bombing the U-boat. Bluefields and U-576 were lost within only minutes of each other, not to be seen again for many years — and not to be identified until Oct. 21, 2014.

Those aboard the 43.5-foot freighter — built in 1917 — escaped with minor injuries. The 220-foot-long U-boat, however, went down with all 45 crew members, according to NOAA documents.

Still intact, the vessels have been the sharp focus of the NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for many years. In fact, documenting sunken WWII vessels off the North Carolina coast has been a large goal for the NOAA in order to shed light on an often forgotten slice of America’s history.

Located around 600 feet beneath the water, both vessels are protected under international law, with the U.S. and Germany maintaining ownership of their respective vessels, as is common practice with war graves.

Researchers utilized remote sensing surveying and sonar imaging — along with hours upon hours of archival research — in order to identify the vessels. The U-boat, Hoyt said, is unmistakable.

Wedged in a period of conflict when people sacrificed their lives for their country, the vessels highlight a lesser-known aspect in history, said John Bright, a maritime archaeologist for the National Parks Service.

“It’s important simply to bring awareness to people that WWII [had such a] far reach that it encompassed literally the entirely globe,” he said, “right up to the North Carolina shore.”

With the goal of education in mind, the NOAA, along with Bright and Hoyt, hopes that this discovery and identification will urge others to dive into the history of the Second World War, so much of which is umbrellaed by more memorable moments, such as the Battle of Normandy and Pearl Harbor. Americans, Hoyt said, often overlook the fact that conflict reached the coastline of the U.S.

“There were bodies washing up on the shores of North America,” he said.

After years of dedication, Hoyt described the feeling of finally identifying the wrecks with three words: elation, relief and satisfaction.

“We’re basically running this whole thing off a theoretical model. The longer you go without finding it, you start to scratch your head,” he said.

For John Bright, a North Carolina native, the identification has also been a long time coming.

For his thesis research in grad school, the East Carolina alumnus performed archival reconstruction and analysis of the battle resulted in the vessels’ watery fates in order to narrow in on the locations of their final resting places. After taking a job with the National Parks Service, joined a NOAA-led team and continued to collect data and refine the models.