Tracking the Missing Metridiums of San Diego's HMCS Yukon

Allison Vitsky SallmonAlthough corynactis anemones and sponges had grown back on Yukon, giant plumose anemones had not—yet.

The HMCS Yukon, the crown jewel of San Diego’s famous Wreck Alley, is one of my favorite dive sites in the world, and it’s right in my backyard.

When the water is clear and calm, this 366-foot Canadian destroyer is an unbeatable dive. It rests on its port side, with its deck facing the Pacific, and is layered with invertebrate life, often attend- ed by a school of blacksmith, a great place to spot passing pelagic creatures. Best of all, I can do two leisurely Yukon dives and still be home in time for lunch. Although the superstructure—including recognizable items like a crow’s-nest, smokestack and guns—is especially popular with most divers, I’ve always been drawn to the propeller. Few divers spend time at this part of the wreck, so it always seems peaceful, and best of all, it’s absolutely covered with large plumose anemones, mostly Metridium farcimen.

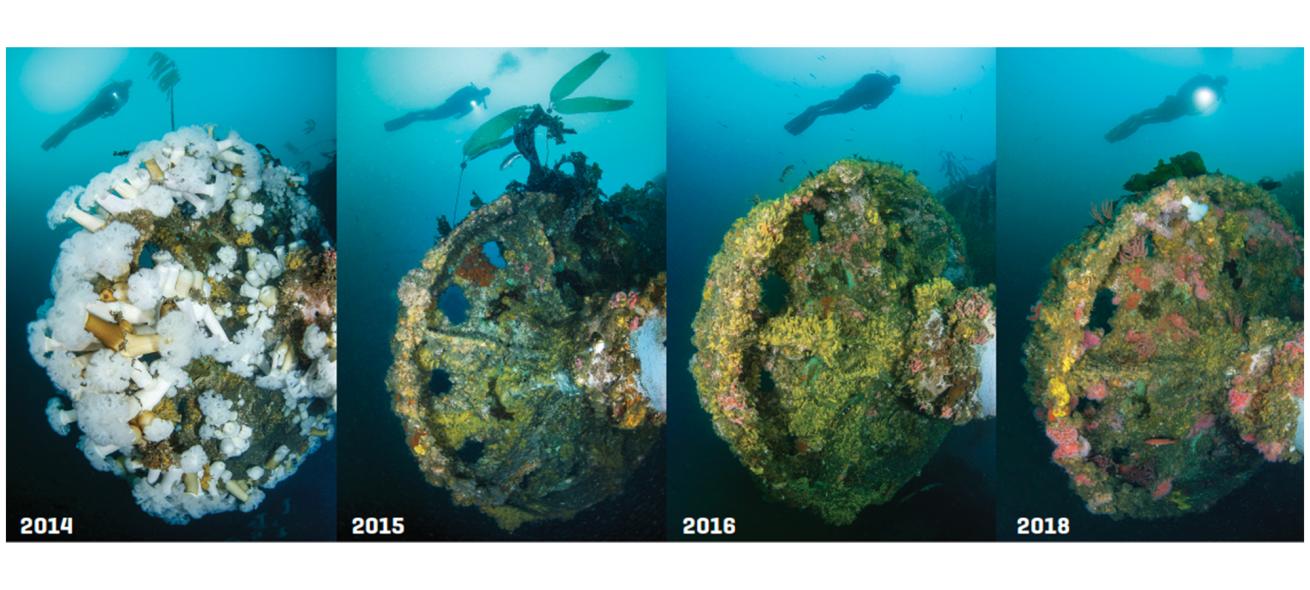

I know what you’re thinking. Why the fuss about the metridiums? Although we certainly have them in Southern California, we’re at the southern edge of their range, so—unlike colder locales such as Puget Sound or Alaska—viewing them at recreational depths can take some effort. The Yukon has long been the very best place in San Diego to admire them, so many in one place that it’s rumored that juvenile polyps were attached to the ship when it was transported from Canada for reefing. As recently as the end of 2014, the Yukon wreck, and especially its propeller, was absolutely covered with giant plumose anemones so densely packed together that identification of the puffy cloud as a propeller would be difficult for anyone who didn’t realize they were exploring the stern area of a shipwreck.

A couple of warm-water events and 10 months later, everything had changed. One Saturday in September 2015, I found myself gazing in disbelief at Yukon’s denuded propeller, patches of bare metal clearly visible. The dreamy layer of anemones, unable to withstand the rise in water temperature, had completely disappeared.

I’m not the most emotional person, and certainly not while I’m diving, but I couldn’t hold it together. There I hovered, 90 feet below the surface, staring at a propeller that was unfamiliar to me, that seemed nearly devoid of invertebrate life, and I had to clear a sudden flow of tears from my mask. I reminded myself sternly of the motto of the HMCS Yukon: “Only the fit survive.” I had to have faith that the water would cool again, and that the invertebrate life I loved so much would regrow.

Allison Vitsky SallmonYukon's propeller in 2014, covered with giant plumose anemones, and in 2015, 2016, and 2018, with regrowth beginning.

Despite my resolve, it was tough to maintain a positive attitude over the year that followed. I quickly noticed plumose anemone numbers seemed impacted everywhere we used to see them in Southern California—they were missing altogether at some sites and were reliably viewable only below recreational depths at others. This wasn’t the only tear- inducing loss, however: Shifts of fish populations led to die-offs of California sea lions, so much so that moms abandoned their newborns, leaving only one or two pathetically skinny babies at what had once been Southern California’s busiest pinniped rookeries, even during the height of pupping season.

Making matters worse, Southern California’s kelp forests—beset by warm water, invasive species and a series of strong storms—had been nearly decimated, and much of the marine life that normally inhabited the forests disappeared. Surface swims were certainly a lot easier without the concern of entanglement, but few divers were happy about the trade- off. Reef dives that had previously concluded with a slow, luxurious ascent through kelp, during which I scoured the leaves for nudibranchs, became an abbreviated, square-profile affair. And forget about admiring dreamy sun rays filtering through the stalks—I was lucky if I could find a single intact strand. I began to venture farther and farther offshore, ultimately resorting to repeated day trips to Santa Barbara Island (a tiny dot nearly 40 miles offshore that had one of the only semi-healthy, photographically productive kelp beds left in the region), a costly and exhausting process that involved an extremely early wake-up call and eight hours of travel time for three dives. It was worth the pain, but by the second year of this, I was sleep-deprived and missing my disposable income.

It wasn’t all depressing, of course—drysuits became increasingly optional, the visibility was absolutely spectacular, and trips offshore yielded fantastic and novel photo opportunities. An influx of Velella velella (blue, wedge-shaped floating hydrozoans commonly called by- the-wind sailors) attracted mola molas in larger-than-usual numbers, so viewing these bizarre-looking bony fish became far more common. Close interactions with smooth hammerhead sharks, normally a shy species, were reported up and down the coast; a whale shark was spotted near Catalina Island; and a local diver captured an amazing photograph of a school of mobula rays. Unusual jellyfish also began to appear.

After one particularly depressing exploration of a local artificial reef, I ascended to find myself surrounded by huge black sea nettles. Two months later, when I peered over the railing of a dive boat and spotted an Australian spotted jellyfish pulsing past, I could hardly believe my eyes. I must admit that I didn’t give a darn that this exotic animal seemed far from home; in fact, I doubt I’ve ever entered the water faster.

Allison Vitsky SallmonIn 2017, the sea lion populations began to rebound.

By fall 2016, things finally seemed to be normalizing. Water temperatures had dropped, and my favorite Santa Barbara Island kelp bed, which had started to become a bit sparse and tattered, began appearing thicker. Not long thereafter, new kelp growth started popping up at shallower sites along the San Diego coast. I spent a few glorious dives exploring these new forests, utterly delighted at the perfectly formed baby kelp and the once-everyday creatures among the leaves: A topsnail! A crab! A kelp- fish! The situation seemed so novel that when the surface strands became frustratingly tangled around the rungs of my friend’s boat ladder, we looked at one another and hooted our utter joy. The kelp had regenerated so much that it was a pain in the butt again! The local sea lion populations had also begun to rebound, and in 2017 I found myself snorting with laughter as dozens of fat, playful pups divebombed me, biting at my camera, hood and fins.

I’d been unable to bring myself to return to Yukon very often during much of this time for fear of what I’d find. Each time I did, I searched for evidence that the plumose anemones had returned. The wreck was lavishly covered with invertebrate life by 2016, but it largely consisted of sponge and corynactis (smaller, brightly colored) anemones. In 2018, however, when I inspected Yukon’s propeller, I finally spotted what appeared to be a small metridium growing among the other invertebrate life. I promptly began diving Yukon regularly once again, and sure enough, the little anemone was growing, and rapidly. In July 2019, I spot- ted two other large plumose anemones nearby. I didn’t even bother to try to pull it together this time—I cheered loudly and repeatedly into my regulator, earn- ing a strange look from a nearby diver. I flashed them an OK symbol, and then crossed my fingers, closed my eyes, and hoped hard: Let three become six, six become 12, 12 become 24 and on and on and on.

Allison Vitsky SallmonGiant plumose anemones are common in colder locales such as Puget Sound, not in Southern California.

NEED TO KNOW HMCS YUKON

When to Go: Late summer through winter (August to January) offers the best conditions, with fall months providing the optimal chance for calm seas and good visibility.

Dive Conditions: Water temperatures at depth range from 48 to 62 degrees F year-round, with coldest water in late spring and early summer and warmest water in late summer/early fall. Stark thermoclines can be present at any time of year, so a drysuit or 7 mm wetsuit with hooded vest, as well as warm gloves, are recommended year-round.

What to Bring: Don’t forget your dive light so you can check out the many hatches, holes and cutouts. Penetration of the wreck is possible for appropriately certified divers.

Suggested Training: Advanced Open Water Diver, Wreck Diver Specialty, Dry Suit Diver (padi.com)

Travel Tips: Book in advance if you’re planning a weekend visit—this popular dive site can get busy. Also, don’t hesitate to inquire about a local dive guide, no matter how experienced a diver you are. The large, tilted structure can be extremely confusing at first (especially if visibility is less than aver- age); diving with someone who will point out the various features can greatly improve any diver’s enjoyment of the wreck.

Contact: Waterhorse Charters (waterhorsecharters.com); Marissa Charters (marissacharters .com)

UNDERSTANDING—AND DOCUMENTING—CHANGE

Repeat Customer There’s no substitute for experience, and nothing takes your diving to the next level like getting familiar over time with a dive site or dive region. Spending a lot of time in the water will help you weed out normal seasonal differences and recognize larger changes in a site’s topography and marine life.

Stay Informed Take advantage of every source of in- formation. In addition to local news and dive-related media, read local dive re- ports and pay attention to social media.

Take the time to discuss what you see with local experts: marine biologists, ocean/climate specialists and others.

Keep Track Maintaining a written and photographic record of the marine life changes you see over a multiyear period may help you see a larger story, even if in retrospect.