Adrenalin Overdose

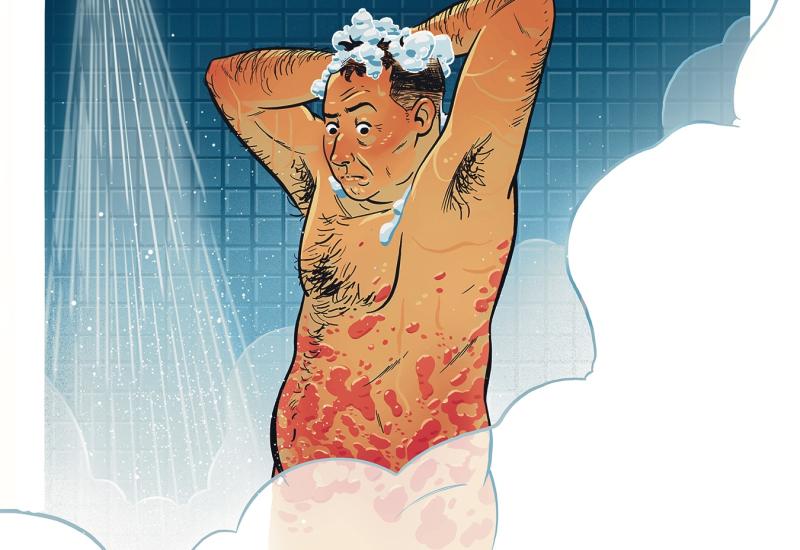

Carlo GiambarresiRushing to take in a massive wreck comes at a cost.

Glenn had just reached the stern of the shipwreck when he heard a tell-tale beeping.

He glanced at his dive computer. He was low on air and had only a few more minutes before he would begin accumulating mandatory decompression time. He couldn’t believe time had flown by so quickly.

Looking around, he spotted his dive buddy, and looked up the length of the ship. They were a long way away from the anchor line and needed to begin heading to the surface.

The Diver

A relatively new diver, Glenn was excited to spend as much time underwater as he could. He had been certified for about a year and already had more than 50 dives in his logbook. He was 35 and in relatively good health with no known medical conditions.

His favorite dive site was any place with a shipwreck at the end of the anchor line. He enjoyed artificial wrecks for the unique opportunities they presented.

As a history buff, though, he really liked “real” shipwrecks — where a ship had gone down in a storm or had been sunk in battle. He didn’t dwell on the potential loss of life on those wrecks but rather loved the history of them. He liked to imagine what life was like for the sailors on board and what they experienced when the ship went down.

The Dive

It was a clear, sunny day when the boat arrived at the dive site. Surface conditions were calm.

Glenn and his buddy listened to the briefing, but they were focused on making the dive. It was on each of their bucket lists, and both divers had studied it in dive magazines since they were first certified.

The shipwreck rested on the bottom at 120 feet. The upper structure for the large wreck came to within 60 feet of the surface. The ship was more than 400 feet long and 50 feet wide.

The boat crew tied off to an anchor buoy permanently attached to the bow of the ship. In the final briefing, the divers learned there was a strong current on the wreck. The divemaster indicated they should stay to the port side of the ship and stay close to the deck. Visibility was better than 60 feet, he said.

A common misconception is that a safety stop is mandatory at the end of every dive, or every deep dive. It isn’t. If it were, it would be a decompression stop.

Glenn and his buddy were the first divers in the water. They followed the anchor line to the bottom, enjoying the sight as the shipwreck materialized in front of them.

The Accident

Glenn followed the ship’s main deck from the bow toward the stern. They were in 95 to 100 feet of water throughout the dive. Glenn and his buddy stayed on the wreck’s port side, as the divemaster told them to, with a few swims to the middle of the ship to look at unique features. Glenn stopped several times to take photographs and look at sea life that was growing on the deck.

When they reached the stern, Glenn and his buddy photographed each other beside the ship’s name, each imagining making his photo his social-media profile shot as soon as they got home.

They were 19 minutes into the dive when Glenn’s dive computer began to signal that he was running low on air. He was also startled to realize he had only a few minutes of no-decompression time left.

Glenn looked around and signaled to his buddy that it was time to head to the surface. His buddy checked his computer and saw he was in the same situation.

Using hand signals, they agreed they didn’t have time to swim back to the bow and then make their ascent along the anchor line. They decided to make a free ascent to the surface but angled toward the anchor line, hoping to meet it halfway up. They wanted to make sure they surfaced by the boat.

As they ascended, they had to swim against the current. When they finally reached the anchor line, they were both very low on air. They decided to ascend directly to the surface without making a safety stop.

Back on the boat, Glenn informed the crew of their ascent and the potential problems. He thought they might have ascended rapidly, as well as omitting their safety stop and pushing the limits of the dive.

Neither diver had any symptoms, but the crew directed them to skip the second dive and to be on the lookout for possible symptoms of decompression illness.

Analysis

One of the first rules of diving — after never hold your breath — is to swim slowly and not to be in a hurry. Sometimes that is difficult to do when you want to see an entire shipwreck. Your first urge is to swim as fast as you can to take it all in. That’s a shame because you won’t appreciate any of it if you are racing over it.

In Glenn’s case, he swam slowly enough, but he didn’t account for the sheer size of the wreck. He should have planned to explore half of the wreck, and then come back later for the other half. The depth and current made it impossible for him to see the entire ship in the bottom time he had available.

He didn’t monitor his bottom time and air supply properly either. If he had, he would have realized he was using his air supply more quickly than anticipated. He could have turned the dive and returned to the anchor line so he could make a controlled ascent without fighting the current. Then he would have had enough air to complete a safety stop.

A common misconception is that a safety stop is mandatory at the end of every dive, or every deep dive. It isn’t. If it were, it would be a decompression stop. A safety stop is recommended to add an additional margin of safety at the end of a dive.

That depends on air supply though. You should never attempt to make a safety stop at the end of a dive if you don’t have enough air to do it. Doing so could cause you to run out of air while still underwater and lead to a rapid ascent from 15 feet. A rapid ascent while breath holding from safety-stop depth can easily cause an air embolism.

Some people will also question whether Glenn and his buddy should have been placed on oxygen on the surface since they likely violated their decompression status and skipped the safety stop. The answer to that is no. Observing them for signs and symptoms of decompression illness is the proper course of action. Placing them on oxygen first aid, without being symptomatic, could delay getting them to definitive care, a recompression treatment, because they might feel fine when the boat reached the dock, only to experience symptoms and not seek help until much later. The typical delay between the last dive and seeking medical attention is 17 hours.

Of course, in a situation where decompression illness is a possibility, you do not want to make another dive that would increase the nitrogen gas load in your body. The boat crew handled this situation in a textbook manner.

Lessons for Life

- Plan your dive and make it realistic. Many divers plan their dive based on what the computer tells them during the dive. That isn’t always realistic when it comes to wreck diving or a diving with a goal. You should know your potential bottom time and plan accordingly.

- Monitor your bottom time and air supply. Running out of gas on the freeway is embarrassing. Running out of breathing gas during a dive can be deadly.

- Learn the symptoms of decompression illness and how to administer oxygen first aid. Take a course in oxygen first aid administration. It will cover how and when to use oxygen in a diving emergency, along with when to seek definitive care.

About Lessons for Life

We're often asked if the Lessons for Life columns are based on real-life events. The answer is yes, they are. The names and locations have been removed or altered to protect identities, but these stories are meant to teach you who to handle a scuba diving emergency by learning from the mistakes other divers have made. Author Eric Douglas takes creative license on occasion for the story, but the events and, often, the communication between divers before the accident are entirely based on incident reports.