Diving to Preserve the USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor

One of our nation’s most sacred sites lies underwater, seen up-close by only a few divers a year: the USS Arizona, sunk in Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor in a horrific 1941 attack that brought the United States into World War II. Many people ask the big question: Can you scuba dive in Pearl Harbor? The answer is simple—probably not. But a few professionals dive this World War II memorial to help protect and preserve its history.

History of the USS Arizona

As an underwater archaeologist, you could say I have a career in the misery business.

For more than 30 years much of my job has been to document the remains of human mistakes and tragedies that litter the floors of lakes, rivers and oceans across our planet.

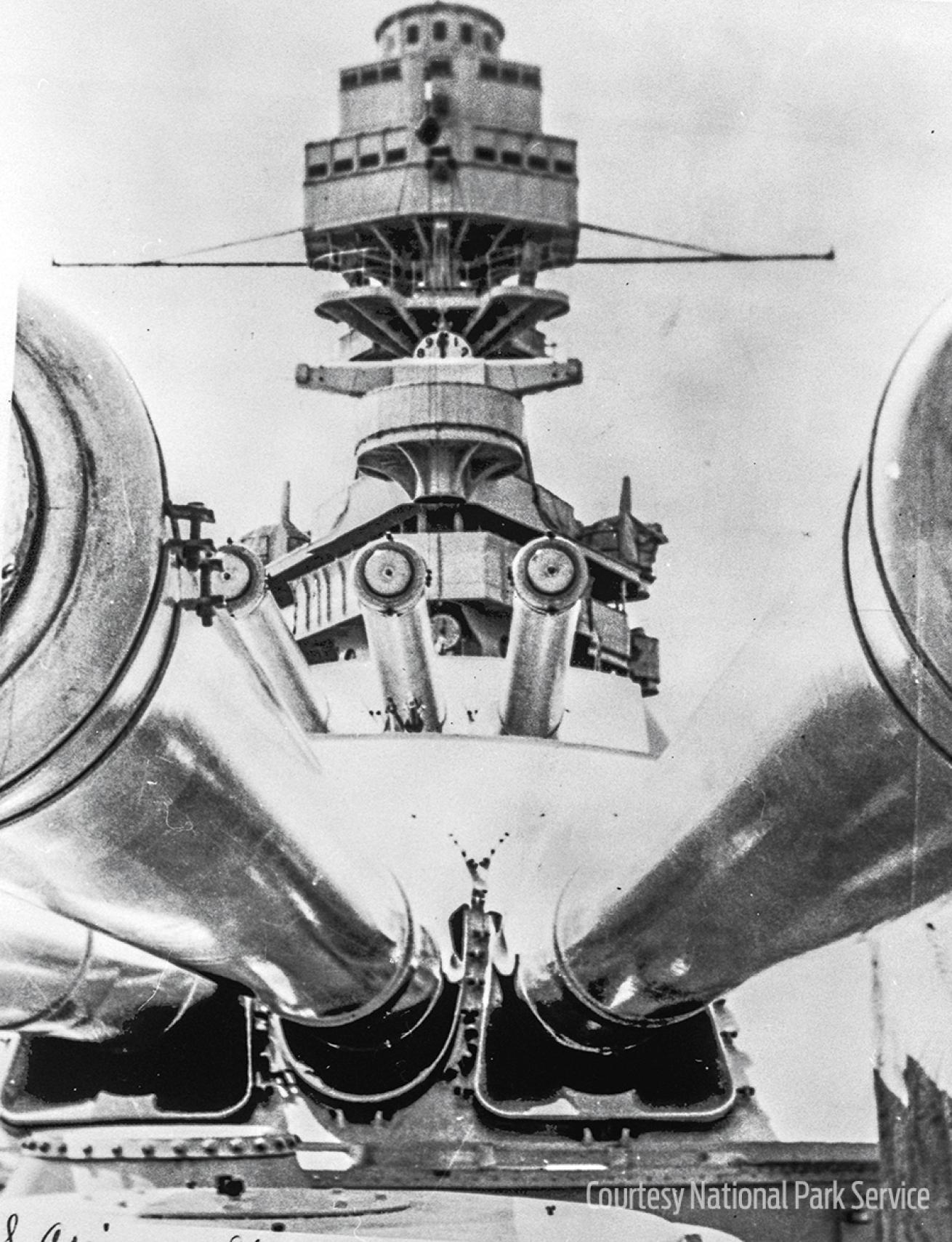

Courtesy National Park ServiceBefore it was attacked in Pearl Harbor, the USS Arizona was the most fearsome tool in the U.S. Navy’s arsenal.

If ships are the stuff of dreams, these shattered bones that festoon reefs and islands around the world are nightmares. Some, like the largely still-intact ships that bumped into the shallows of what is now Dry Tortugas National Park, are merely disturbing, leading to bemused speculation as to how (or if) these ships ended up here by accident.

Others are full-on night terrors that wrench you from your daily life and hit you with a sucker punch to the gut that takes the wind right out of you. Seeing the carnage of these wrecks up close underwater leaves you breathless for days, weeks — or in the case of Arizona, forever. After decades of diving on hundreds of sites, I can say without exaggeration that no shipwreck invokes a nightmare more awful than the USS Arizona.

USS Arizona was the second and final of the Pennsylvania class of super-battleships designed and built for the United States Navy at the beginning of the 20th century. Launched with great fanfare from the Brooklyn Navy Yards in 1916, Arizona was the biggest, baddest, most fearsome tool in the United States Navy’s arsenal of naval weapons.

Armed with four huge turrets and a total of twelve 14-inch guns with a maximum range of almost 12 miles, Arizona could cruise for more than 7,500 miles at speeds of up to 21 knots. For 35 years, this mighty floating fortress patrolled the waters of the world, unsubtly projecting and protecting American power and influence to friend and foe alike. By December 1941, after a distinguished career in the Atlantic followed by an extensive overhaul and modernization, Arizona assumed the role of flagship for the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

For the sailors and marines on USS Arizona, daily life must have been more like an extended Boy Scout adventure than the grim business of naval war. The ship had a barber shop, a baseball team and even an ice cream parlor. Looking at the National Park Service’s archive of fading images illustrating shipboard life — memorabilia of ship-sponsored dances, boxing matches and cruise books that look like yearbooks — the overwhelming impression is of youthful joy and naiveté. One doubts that many of its crew expected to see the darker side of modern warfare, much less be on the receiving end of it.

The Pearl Harbor Attack

On the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, anything that resembled joy or naiveté for Arizona’s crew evaporated in milliseconds. In a cataclysmic raid that heralded the end of the battleship era, aircraft from six Japanese carriers sprang an incredibly well planned and effective surprise attack on the naval forces of Pearl Harbor. Tied up with the rest of the fleet on Battleship Row with a full load of fuel and ammunition, Arizona was a sitting duck in the narrow confines of the harbor. After weathering several minor hits and near misses, Arizona was struck by a 16-inch armor-piercing naval shell reconfigured into an aerial bomb that glanced off the Number 2 turret and pierced the forward powder magazine.

At approximately 8:06 a.m., a colossal secondary explosion obliterated the forward half of the battleship along with 1,177 of the ship’s crew of 1,511 sailors and marines. As National Park Service archaeologist and former chief of the Submerged Resources Center Dan Lenihan notes, for many aboard Arizona, the single most important event in world history — World War II — lasted a sum total of 10 minutes.

Arizona sank to the shallow floor of Pearl Harbor and burned for two days, despite the heroic efforts of naval personnel to contain the damage and save other vessels that were relatively undamaged. As the fires were quenched and some semblance of order restored, salvage crews began the frantic process of triage for a fleet of sunken and damaged ships vulnerable to follow-up attacks. Arizona was too far gone to be refloated or saved — after several years of painful salvage work during which almost 200 bodies were removed from the ship, the vessel was declared a total loss. The men who remained unrecovered were declared buried at sea.

Courtesy National Park Service/Brett SeymourA black-and-white photograph of the USS Arizona as it crossed New York’s East River en route to the New York Naval Yard, 1916.

Scuba Diving to Protect the USS Arizona

Although the ship was lost, it was never forgotten — “Remember Pearl Harbor” became the rallying cry for a nation fully engaged in the pursuit of war with both Japan and Germany. After the war, Arizona remained a focus for reflection and remembrance; in 1962, the current memorial was dedicated. In 1980, the National Park Service joined with the U.S. Navy to tell the story of Arizona to a public still deeply moved by the heroism and losses of December 7, 1941.

As an underwater archaeologist for the National Park Service, it is my duty and honor to help preserve and protect the remains of USS Arizona and its crew. Almost every year since 2000, I have had the privilege of diving on a site that few others can access. When I tell fellow divers that I dive on Arizona as part of my job, they inevitably ask if they can dive it too. When I say “probably not,” they usually ask why.

The reasons the site is not open to the diving public are numerous and sensible: First, it’s one of our nation’s most important war graves and deserves respect for the men who remain entombed within the vessel. Second, it sits smack in the middle of one of the Navy’s most important strategic assets — Pearl Harbor is still an active naval base and remains on hair-trigger alert in these uncertain times. Third, the occasionally carnival atmosphere of a commercial dive charter would detract significantly from the somber remembrance of sacrifice and loss the memorial was created to foster.

But what is it like to dive on Arizona? Confusing, disorienting, sad and uplifting. Visibility in Pearl Harbor is rarely good and often bad. You are exploring a 608-foot long, 100-foot wide battleship in a sphere of visibility that’s about 12 feet in diameter. The site is heavily overgrown with sponges, corals and other marine life, with a color pallet of olive and muddy brown as muted as the visitors to the memorial. Corners and edges once polished and painted in Navy gray are rounded, bent, cut by salvage teams or shattered by blast and fire.

Here, gradually, the somber sense of place begins to sink in as a slow, dull realization of tragedy. Your mood is pulled along a declining spectrum from normalcy to sadness as you see areas where fish have cleared the teak decking to lay their eggs, or a bit of new coral growth, and then suddenly a sailor’s shaving kit or a cereal bowl in the galley area. Ultimately it’s impossible to conceive of the tragic destruction of hopes, dreams and potential that happened on Arizona that Sunday morning as a total concept — just as it’s impossible to see the ship in toto, one must experience it as individual vignettes that reach a crescendo. This was somebody’s shaving kit, this was somebody’s cereal bowl — men much younger than I walked these decks, loved this ship and loved their comrades. They are all lost now, some killed in a nanosecond, the more unfortunate burned, suffocated by oily smoke, roasted alive or drowned.

Some of the survivors lived lives full of families and joy after the war. In death, many of them feel the pull of Arizona and ask to be returned to their shipmates for burial. I have had the honor of interring the cremated remains of two Arizona survivors in the quiet depths of barbette Number 4, a place where they can rest with their friends and shipmates from the Arizona shop and baseball team.

Swimming forward, one of Arizona’s most amazing revelations is its still-intact Number 1 turret. Larger than a greyhound bus, the huge structure is thinly veiled beneath the murky waters of the harbor. The other three turrets were removed from the ship, their guns reused in other battleships or as coastal-defense gun emplacements on the far shore of Oahu, but this one remains.

Moving forward toward the bow, the final evidence of Arizona’s end can be seen where the ship narrows. Here the explosion of the forward powder magazine — contained vertically within the armored decks of the ship — reached a critical point and blew the four-inch armored sides of the ship outward like a splayed banana. As the blast moved forward, it destroyed the interior walls; at least three decks collapsed downward like a stack of pancakes. Forward still, the structure of the bow remains attached to the wreckage astern yet somehow serene. As all of these pieces of the puzzle come together — not in a single dive, but over the course of several — it brings home the sadness and loss of this amazing place.

Courtesy National Park Service/Brett SeymourAs an underwater archaeologist for the National Park Service, Dave Conlin is one of few people in the world who has dived the USS Arizona. Scuba diving the ship is part of his work to preserve and protect the remains of the USS Arizona and its crew. Here, he is photographed on the ship's starboard gunwhale.

What Will Happen to the USS Arizona Shipwreck?

But what is the National Park Service doing to and for Arizona? In addition to questions like “What’s down there?” and “Can I dive it?” most visitors ask about the oil that seeps from the vessel at a rate of between 2 and 4 quarts per day. “Why don’t you pump it out?” is a reasonable question. Along with the remains of nearly 1,000 sailors and marines, this scene of terrible tragedy and sacrifice still contains an estimated half-million gallons of fuel oil inside a deteriorating hull. As the battleship gradually rusts and collapses, the oil’s release is inevitable. Simple questions such as “How long do we have until the ship loses its integrity?” and “Is there anything we can do to delay this deterioration?” lead to complex answers with a dizzying number of variables, many of which we don’t fully understand and perhaps a few of which we have overlooked completely. To provide complex scientific answers to simple questions about the ship’s future, a team from the Valor in the Pacific National Memorial and the Submerged Resources Center started an ambitious research program in 2000 to develop a long-term preservation plan for the ship.

The short answer is that we can’t remove the oil from the ship and not destroy it as a structure. Unlike a car or an oil tanker, Arizona was built to withstand battle damage, and its fuel is spread over hundreds of individual tanks. To reach each one would entail removal of large portions of the ship, and intrusion into a war grave. Caught on the horns of a dilemma that balances preservation with mitigation of a potential environmental threat, we are trying to be both respectful and responsible. As stewards of this remarkable, tragic yet inspiring site, the Park Service is partnering with many scientists and the Navy to determine the best course of action.

In the meantime, our efforts are directed at discovering how long we have to make a decision and what possible options we have to slow the deterioration. So far, we have learned that we have some time to come up with the most-efficient, least-intrusive and best course of action for USS Arizona and her crew.

As we gather more information and complete more studies, we will continue to share and promote the story of a ship that is now 100 years old. I expect that I will have more dives on Arizona, and while I cannot take my diving friends with me, I can share the story of a shipwreck that can change a diver’s life, a nightmare of fire, smoke and loss that ultimately redeems itself as the story of the courage and sacrifice of the sailors and marines lost that day. We still remember Pearl Harbor, and Arizona.

How To Visit the USS Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor

The USS Arizona Memorial is the most popular tourist attraction in the state of Hawaii and sees more than 1.8 million visitors per year. With a site as busy as this, a little planning can go a long way. Entry to the memorial is free, but reserving a spot in advance (highly recommended) costs $1.50 per ticket (one person can reserve up to six tickets). About 2,600 USS Arizona Memorial tickets are available each day at recreation.gov, or you can call 877-444-6777. Tours to the memorial run every 15 minutes from 7:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. (150 visitors per tour). If you visit the Arizona Memorial, don’t forget the USS Missouri — the ship on which the Japanese formally surrendered — the Pacific Aviation Museum and the submarine USS Bowfin that lie close by.

Courtesy National Park Service/Brett SeymourPersonal items from a sailor’s shaving kit are tagged on the wreck of USS Arizona. Artifacts like these are reminders of the lives lost during the attack on non deck who died on USS Arizona after it was attacked at Pearl Habor. 1941.

Courtesy National Park Service/Brett SeymourAlong with the remains of nearly 1,000 sailors and marines, the USS Arizona shipwreck holds an estimated half-million gallons of fuel oil inside a deteriorating hull. The National Parks Service is working to develop a long-term preservation program for the ship, using 3-D mapping techniques as one of its tools.

Read more about wreck diving in national parks, famous shipwrecks, find our guide wreck diving worldwide and see more amazing shipwreck photos here.