Citizen Science Rock Stars Ned and Anna DeLoach Make Fish ID Fun

We float in a womb-like darkness barely penetrated by the full moon overhead. Clusters of bright particles drift by, mirroring distant constellations — it’s impossible to say where sea ends and sky begins. All sense of scale is lost, along with time, distance, motion. We are suspended in the void. But we are not alone. As our perceptions adjust, microscopic beings shimmy in our lights, animals the size of a grain of rice doing crazy hula-hoop dances, frenzied, wild stuff. And then, just as fast, off into the darkness they fly. All, that is, but one.

Gliding gently downward is a creature that seems to be all head. It’s the size of a thumbnail, its little arms just barely sprouted. A juvenile squid, perhaps?

But it’s something rarer still, the very creature we have been looking for: a post-larval octopus, finished with its early, open-ocean stage of life, seeking a place to settle on Buddy’s Reef. What propels this tiny, translucent thing that has beaten staggering odds to return to what might be its natal reef? Where has it been, and where is it going? There’s no way to know.

Or is there?

Tim PetersMarine Life Education weeks include chances to make survey dives by boat with the DeLoaches (at center) as well as on Buddy’s Reef.

On the Hunt

“I’m not a scientist. I’m a naturalist, just like you are,” Ned DeLoach tells the eager divers trailing him around Buddy Dive Resort morning, noon and night.

It’s a notion he will return to during the five days we’ll spend learning fish-survey techniques from Ned and his wife and partner, videographer Anna DeLoach, at Buddy Dive’s Marine Life Education weeks, repeated annually for the past 15 years, to capacity crowds.

Ned, 74, is the Mr. Rogers of diving, an ebullient, young-at-heart Southern gentleman whose years as a teacher seem to impel him to encourage and make time for others. “That’s why I talk so much,” he says. “I’m always trying to teach.”

Founder and co-author with Paul Humann of the REEF Identification series, the definitive fish-ID guides for divers, Ned is the better-known DeLoach. But the real fish whisperer is Anna, 64, a quiet presence marked by her bobbing silver ponytail, to whom all creatures great and small — divers too — are drawn.

They didn’t start out this way. In the 1970s, Ned was a Florida-based phys-ed teacher who financed his passion for dive travel by freelancing destination pieces for dive magazines. At the time he met Anna, in the ’80s, she was co-owner of a Bahamas dive operation propped up by her day job in IT.

Attempting to identify the fish he was describing, Ned became increasingly frustrated in those early days. “I bought a few books in the ’70s and got discouraged very quickly,” he recalls. The technical tomes were “all very sciencey,” not written for divers.

Tim PetersAnna DeLoach (left) on a survey dive; Ned with students in Buddy Dive’s classroom.

Meanwhile, Humann — who was running one of the first liveaboards anywhere, Cayman Diver — was experiencing the same frustration. The two were introduced, and in 1989, their Reef Fish Identification: Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas was released; along the way, the pair co-founded Reef Environmental Education Foundation to gather data on fish biodiversity and abundance based on census methods popularized by bird-watchers. Eventually the DeLoaches would chuck all else for a life underwater, in the process becoming ambassadors for what today is widely known as fish ID.

Show up 10 minutes before Sunday evening’s program at Buddy Dive’s beachside Blennies restaurant — christened to honor Anna, a prodigious spotter of the shy fish that flourish in Bonaire — and you won’t get a seat. More than 100 divers are perched anywhere they can, rum punches in hand, waiting for the week’s opening act. “Bird-watchers would be happy to find 20 species” on an hourlong outing, Ned begins. Life is better for divers. “You can regularly see 20 different animals on your way to the bottom.”

For some, it’s not necessary to identify those fish in order to enjoy them. But divers are a curious breed. “When you come back from this week, you’ll own these fish,” Ned had told me earlier, referring to the species he would introduce that night — and challenge us to find on Bonaire’s reefs. “They will be yours for life. Gives you a foundation to grow on for years to come.”

The 20 targets are tallied on a sheet the DeLoaches distribute — three kinds of blennies, a sergeant major with eggs, frogfish and seahorse, on the small end of the scale, up through eagle ray and turtle. Each find is worth 5 points; 65 points earns a signed copy of the waterproof REEF FISH-in-a-Pocket companion guide.

Ned shares advice the DeLoaches follow when they dive. First, “dive slow. As any hunter can tell you, moving eyes don’t see movement well,” he says.

Second, think small. “We all love the big stuff, but if that’s all you look for, you’ll soon tire.”

Have patience. “See something that looks odd? Stop and watch a bit. Give yourself over to a moment underwater.”

With the help of an overhead slideshow, Ned explains that there is no successful fish ID without behavior, often the definitive clue in identification since so many juveniles look unlike their adult selves.

Understanding behavior also provides the “why” in studying the sometimes-strange life of undersea creatures. For example, how to recognize courtship? “Look for male fish doing dopey, out-of-the-ordinary sorts of things,” he says, “just like unattached human males when the bars begin to close on weekend nights!”

A natural showman, Ned radiates an enthusiasm that is catching. “Anthropomorphism a no-no in science? Bull!” he roars, as close as he gets to profanity. “Animals often behave so much like us, it’s difficult to ignore.”

Ned DeLoachAn unidentified larval octopus plays peek-a-boo with photographer and naturalist Ned DeLoach.

One Fish, Two Fish

Ever since Adam awoke in the Garden, humans have felt the urge to count and name. It’s in our DNA. Some of the first branches of learning that the ancients thought of as “science” — astronomy, for example — evolved from observing, counting and naming.

“Citizen science” is also an old idea. Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, Charles Darwin — all were “gentlemen scientists” without academic affiliations who nonetheless are remembered for some of the most significant scientific contributions of their day.

"The world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings.” — Robert Louis Stevenson, A Child’s Garden of Verses

In our time, citizen science — a term coined in the 1990s — often refers to projects that require vast accumulations of data to reach significance, such as field surveys. “Purpose-driven” travel — a trend that has steadily gained ground since the early 2000s — has been embraced by an industry looking for ways to keep divers in the water. Citizen science was a natural fit.

Ned and Anna are old Bonaire hands who teach citizen science here for a reason. “Bonaire is the best access to animals there is,” Ned says. “That’s because of so much shore diving. You can stay in the water for hours, or go back to the same spot every day.”

Most convenient of that diving is Bonaire’s many “house reefs,” including Buddy’s Reef. Take one look off Buddy Dive’s deck and you just might want to jump in fully clothed — the sun-dappled, bright blue water is as alluring as a gemstone; you can’t look away.

But before we get wet Monday morning, a couple dozen divers gather just off the deck in Buddy’s comfortable classroom to take a Fish ID intro class with Ned and Anna — offered free during Marine Life Education weeks — followed by a basic survey dive.

For Buddy Dive, the commitment to educating guests and staff goes well beyond one month a year. “If they know what they’re looking at, divers enjoy it more, and we get more return guests,” says Augusto Montbrun, Buddy’s longtime dive operations manager. Marine Life Education weeks were instantly successful; Montbrun read the tea leaves and enlisted the resort’s owners to support training instructors to teach fish ID year-round. The comment he’s most pleased by on guest evaluations of Buddy’s dive staff: “Knowledgeable.”

Jennifer O’NeillEvidence of healthy reefs: naturally occuring staghorn coral. Five Bonaire dive ops, including Buddy Dive, cooperate to nurture Bonaire’s corals.

But he doesn’t discount the gentle spell cast by Ned and Anna. “They helped put Bonaire on the map when it comes to conservation,” Montbrun says. “They change minds.” And win hearts. Heather Tallent, co-owner of Blue Planet Scuba in Washington, D.C., is leading a group of 21 divers, here this week largely because of the DeLoaches. “We’re all kind of groupies,” she says with an embarrassed laugh. Like Montbrun and Buddy Dive, Tallent is committed to conservation. “It’s a big focus of our shop,” she says. Blue Planet also teaches fish ID — “It’s something we expose all our divers to.”

Sponsored initially by the Nature Conservancy, REEF’s Volunteer Fish Survey Project was modeled on Cornell University’s bird survey. Today the REEF database — with nearly 250,000 surveys — is used by scientists, governments and marine-protected areas all over the world. It has become “a model for citizen science,” Anna says, and also a model for other surveys, which have adopted REEF’s methods.

In class, the DeLoaches distribute REEF survey slates, which have places to list species, denote whether fishes observed were “single,” “few,” “many” or “abundant,” and room to sketch unrecognized fishes.

To help us in our search, they share word-association tricks to remember specific fish while surveying (See those fish-ID tips here). Most are goofy — Ned’s favorite expression — and others are serious groaners, eliciting mock catcalls. “If you have a better clue, feel free to shout it out,” Anna says with a good-natured laugh.

But darned if the clues don’t work. When we drop in after class, I immediately spot five of our target 20 right under Buddy’s docks. Although I’d already done several Buddy’s Reef dives, I find myself seeing differently. Instead of concentrating on individual fish — sort of like going to Notre Dame and focusing on a single piece of glass instead of the whole glorious window — I begin to appreciate the bigger picture in a new way.

Midweek we make a boat dive where guests survey Bonaire’s Small Wall site — inaccessible by shore — with Ned and Anna, and a guided snorkel trip to the island’s wilder east side, the latter offered for free. There the mangroves of shallow Lac Bay are nursery to many of Bonaire’s reef species. Buddy’s top-level survey instructor, Dani Hattink, spots a juvenile snook in the bay, a find she and the DeLoaches are excited about.

“Hunting is an instinct for humans,” Ned says. “We’re hunting for science out there.”

But why does all of this matter, beyond the thrill of the chase? In the age of the so-called sixth extinction — happening right now and probably driven by humans — it’s more important than ever to comprehend the world around us so we understand the consequences of massive change, and loss, before it’s too late.

“Hunting is an instinct for humans. We’re hunting for science out there.”

“I’ll give you an example,” Anna says over coffee in Buddy Dive’s cozy waterside breakfast nook before we undertake a Buddy’s Reef “century dive,” where we’ll record 100 species on a single dive. (Challenging but doable on Bonaire — Anna reaches 100 and Hattink exceeds it in an 81-minute dive.) “When the lionfish invasion started, volunteers working with NOAA and the National Aquarium spent hours in field collection and dissection, sneaking buckets of fish into a Bahamas Marriott. The researchers said they never could have collected that data without citizen science.”

Hobbled by pressures from teaching to publishing, academic access to the underwater world can be rare and expensive. “That leaves a big void,” Ned says. “REEF members are underwater a lot — divers are an army that can be deployed.” Compared with the strictures of the university, “we’re free as the wind to go where our instincts and insights take us,” Ned says.

They don’t show signs of slowing. “Every time I go in the water, I feel like I’m on the verge of a great discovery,” Ned says with a delighted grin, his trademark exuberance practically lifting him off his chair. “You’d think after 50 years underwater, you’d see it all, but I still never know what to expect.”

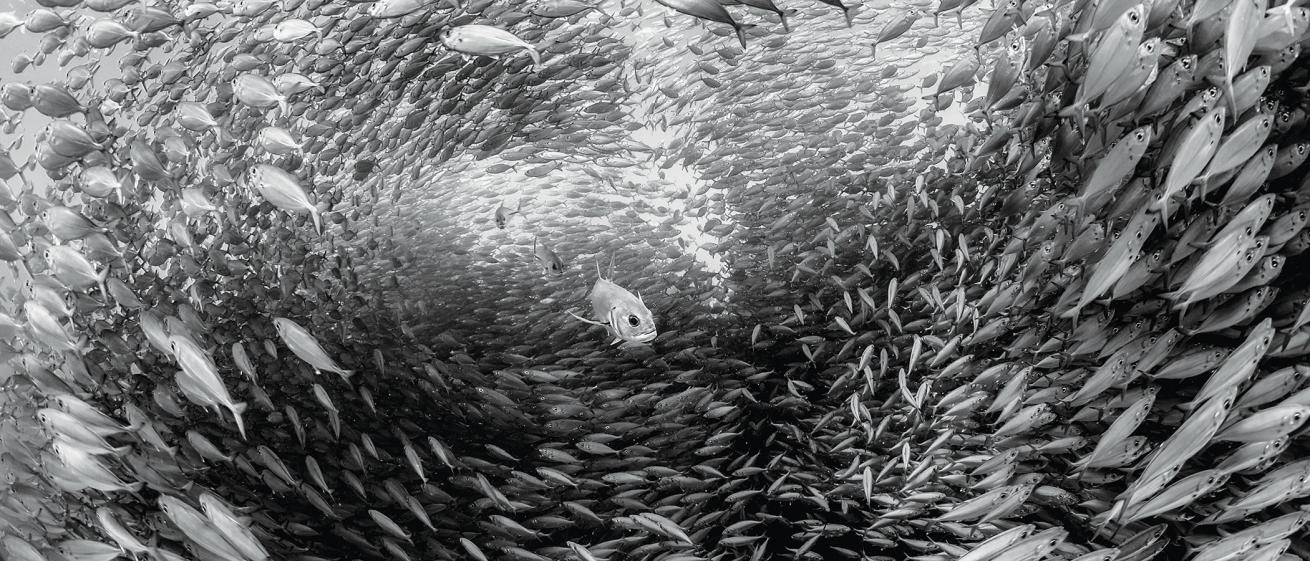

Jennifer O’Neill“Abundant” is an understatement for a baitball at Chez Hines dive site.

Generation Next

We descend with the DeLoaches just after dusk, looking for post-larval animals returning to the reef. Finning over the sand, we’re careful not to disturb Buddy Dive’s growing coral nursery. And then we drift, hanging in the dark at 20 feet to see what comes down.

At first it’s mostly a black canvas streaked with what looks like sea snot — long filamentous bits of white that, to my novice eye, might or might not be alive. But it doesn’t take long before creatures the size of a quarter or a cocktail toothpick begin to emerge — ghostly, transparent beings with minute skeletons and pulsing organs clearly visible. Babies! It’s hard to resist a surge of tender, motherly feeling.

A translucent, pre-juvenile surgeonfish the size of a postage stamp goes by, and then a cone-shaped critter like a candy corn — with wee little waving legs and a startling display of blinking lights — that could be a mantis shrimp. Next comes a glowing blue-and-red rod like a needle — nobody’s sure what that one is.

And then, the crème de la crème emerges in my beam: a baby octopus looking for a place to settle at the end of its multiweek, oceanic larval stage. We waggle our lights so Ned can come and photograph it; like every other sea creature this week, it immediately latches onto Anna. She gently shakes her hand. No dice. She waves the hand around, and the creature jumps to the tip of her upraised thumb — which dwarfs it — but stays firmly lodged. We all begin to giggle into our regs — science can take some unexpected turns! — and we’re laughing uproariously by the time Anna thinks to relax her hand, and the tiny creature leaps free. Ned and I follow its zigzag progress to the bottom, where it zips into a likely looking lair and settles down to become the newest resident of Buddy’s Reef.

Ned DeLoachA post-larval octopus lights on Ned’s finger.

Was this little fellow returning to his or her natal reef? In the past 15 years or so, marine biologists have used genetics to show that many more sea creatures find their way “home” than was previously thought — as many as 60 percent, according to one study. How many octopuses like this one survive the perilous journey to open ocean and back? “Two of thousands?” Ned muses. “One in a million? We really don’t know.”

Skeptics will point out we can never know the story of this individual. But through citizen science, with many eyes upon the reef over many hours, recording and sharing observations in a systematic way, we can piece together the puzzle of the natural world into a picture that can be added to as our understanding and methods advance. Slowly, slowly, knowledge is gained, and answers. What we do with them is up to us.

Marine Life Education

When to Go: Buddy Dive Resort will host naturalists Anna and Ned DeLoach for three weeklong Marine Life Education programs in June 2019. Dates will be announced at buddydive.com.

Operator: Buddy Dive is set up with divers in mind, from its waterside dive deck to its famous drive-through tank fill and pick-up stand, where shore-minded divers can help themselves. The resort’s Drive & Dive package includes accommodations, breakfast, unlimited air or nitrox, and vehicle and airport transfers starting at $812 per person per week.

The Program: Sunday night presentation; Monday Fish-ID class and Level I Reef Surveyor shore dive; optional boat dives and a Level II Surveyor class and dive (additional charges apply); guided Lac Bay mangrove snorkel; Friday night book-signing and awards at a rum-punch cocktail party.