Scuba Diving the Enchanted Isles of Galapagos

“There is Darwin Island, and we have the arch right in front,” Galapagos Aggressor III dive guide and Ecuador native Walter Torres briefs us. He points to an empty patch of ocean aft of the yacht. “Cocos is right here.”

He grins at our puzzled expressions. “I know we can’t see it, but it’s only 600 miles from here.” Not far for migrating hammerheads, but a long way to swim. The remote way station where we find ourselves is a rest area for whale sharks; June through November, it’s frequented by some of the largest around. “Only females, and all of them pregnant,” Torres tells us. The mothers-to-be will spend about a week here; as many as 80 individuals pass through during the season.

Our plan is similar to yesterday’s dives at Wolf Island, with a key difference. Drop down and hang on to enjoy the sharks and reef fish, but when a whale shark comes by, we’ll swim out into the blue for a closer look. “When we have the whale shark, that is the moment when everyone will forget everything,” Torres warns. “You’re going to lose your buddy, you’re going to lose your daddy, your wife, your husband. You’ll forget to check your pressure hose. But please don’t. Check your depth as well.”

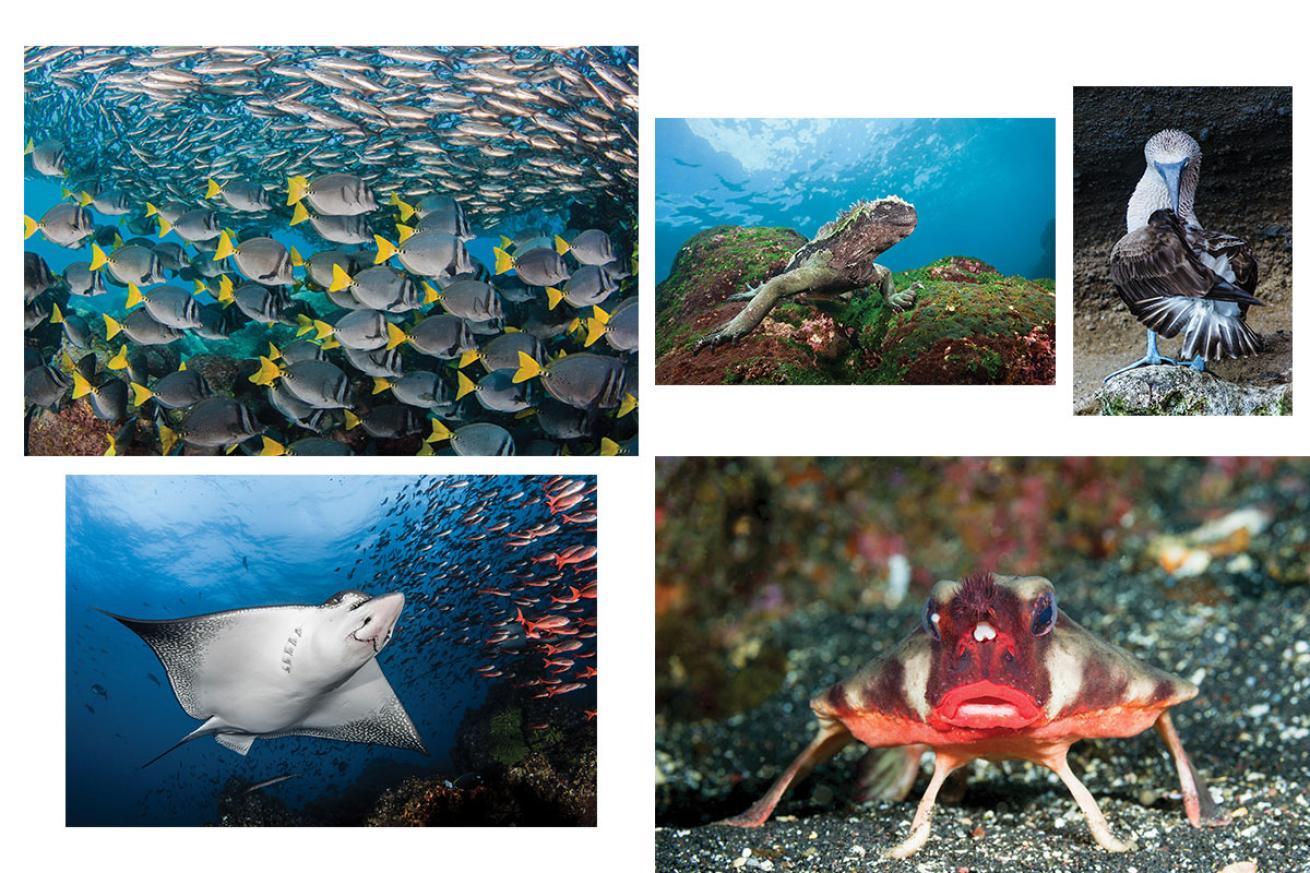

Shawn Heinrichs/Brandon Cole/Juan Carlos Muñoz/Greg LecouerDarwin's Arch, in the northernmost reaches of the Galapagos archipelago, is one of the best places to dive with whale sharks.

Photographer credits, clockwise from top left: Shawn Heinrichs, Brandon Cole, Juan Carlos Muñoz, Greg Lecouer

Hardly five minutes go by after settling on the rocks before I hear the signal. Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. Dive guide Sebastian Barrera raps his tank four times in quick succession and bolts into the blue, the rest of us right on his fin tips. We pass through an enormous school of jacks; as the silvery curtain parts, I see the whale shark waiting on the other side.

It’s hard to comprehend the size of it— just its tail is taller than I am. It’s like riding a bicycle next to a semi—it’s all we can do to keep up with it against the current. It soon outpaces us and vanishes into the distance.

Back on the ledge, I’m out of breath and over the moon. Seconds later I hear another Bang. Bang. Bang. Bang. And we’re off again.

We have incredible luck at Darwin’s Arch; the current remains mild, and we see several whale sharks on each dive, sometimes two at once. It’s a day of mini-marathons as we chase after the leviathans. Despite the exhaustion, no one can bear to skip a single dive.

Each time we come in close, I’m awestruck by their immensity, but also the delicate spotted pattern of their skin, whose impasto, painted look would be right at home next to Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night. Looking at the sharks’ ventral side, the pregnant belly—full of some 300 embryos—is clearly evident in each shark we encounter. At the end of one dive, a whale shark matches my ascent rate, providing the single greatest safety stop of my life.

During our last dive at Darwin, Torres and Barrera measure one of the whale sharks using a length of rope held from head to tail. Though they won’t be able to get the precise reading until they arrive at the Charles Darwin Research Center later in the week, after dinner they unwind the rope to show us their handiwork. It stretches the length of Aggressor’s salon. “Sebastian says 12 meters,” or 39 feet, Torres relays. “I say maybe more.”

Pete Mesley/Antonio BusielloThe endemic Galapagos penguin is the only species of penguin found north of the equator.

Photographer credits, clockwise from top left: Pete Mesley, Antonio Busiello (2)

Living Legends

Three days later we’re driving through the misty highlands of Santa Cruz Island in the middle of the archipelago, on our way to another of Galapagos’ gentle giants: the giant tortoise. Actually, tortoises— at least 14 different species have been identified throughout Galapagos.

These animals are practically synonymous with the islands. In fact, “Galapagos” refers to a type of giant tortoise with a saddle-like shell. We have our first sighting while still en route to El Chato Reserve, when our bus is stopped by a 400-pound tortoise ambling across the road. “We don’t want to get any closer,” Torres explains as we crowd around the driver’s seat. “If he hears us and gets spooked, he will do this,” he says, tucking his arms and head into an imaginary shell. “If he does, no one will be able to move him.”

There are even more tortoises once we arrive. Some measure only a foot or two across; others are as big as the bruiser back on the road—and are likely more than 100 years old. Once on the edge of extinction, these tortoises have recovered thanks to innovative breeding programs that have helped restore the populations of nine of the 11 surviving species.

Endless Parade

Whale sharks and giant tortoises may be some of Galapagos’ biggest draws—literally— but they are far from the only ones. Galapagos straddles the equator at the convergence of three major ocean currents, a unique geography that generates a mix of cold and warm water and has allowed for the arrival and establishment of species from across the Pacific Ocean.

From seahorses and sea lions to marine iguanas and penguins, the diversity of life here is astounding. There are more than 30 species of sharks alone, all protected inside of the 50,000-square-mile Galapagos Marine Reserve.

The current at Wolf Island can be strong and unpredictable, necessitating a quick descent. Once we hit 70 feet, it doesn’t take long for the show to start; where there was only blue water moments ago, dozens of hammerheads are swimming against the current. Though they seem slow and unhurried, they make great headway, and a seemingly endless parade of sharks passes us by—not just hammerheads but Galapagos sharks and oceanic blacktips too.

“You can see all of these different sharks, but they all have totally different behavior,” Torres told us over dinner the night before. “They don’t compete for food or for cleaning.” Between shark sets, the reef offers plenty of entertainment.

David Fleetham/Oceanwideimages.com, Reinhard Dirscherl/Biosphoto/Pete Mesley/Reinhard Dirscherl/Biosphoto/Greg LecoeurBottom-dwelling red-lipped batfish are closely related to other batfish, but are endemic to Galapagos.

Photographer credits, clockwise from top left: David Fleetham/Oceanwideimages.com, Reinhard Dirscherl/Biosphoto, Pete Mesley, Reinhard Dirscherl/Biosphoto, Greg Lecoeur

King angelfish, spiny lobsters, zebra eels and more flit about the rocky bottom. With two brief intermissions for surface intervals, we spend the entire day at the same site. Every dive is as jaw-dropping as the first. It is possible to see hammerheads throughout Galapagos, but it’s only at Wolf and Darwin where you’ll see them in such numbers. These islands also have more current, which strengthens throughout the day. By the last dive it has developed into a 4 knot torrent with a nasty surge. Divers struggle to keep their balance as the strong washing-machine current throws them from side to side.

The sharks are undisturbed by the turbulence, but it takes everything we have to withstand the battering while keeping an eye on our buddies and a hand on our cameras. Thick neoprene protects divers from the worst of the rocks and their sharp, protruding barnacles, but not the bruising.

As the dive reaches its zenith we’re rewarded for our perseverance with a pair of hunting eagle rays that comes in close to chomp through the barnacles and oysters right before our eyes. We hang onto the bottom as long as our tanks will allow before calling it quits. Silkies, whitetips and hammerheads provide a personal escort as we ascend in the blue.

Robby MyersEndemic marine iguanas.

Fernandina and Isabela

After three days of nonstop shark action, it’s time to say goodbye to Wolf and Darwin and head to the western edge of the archipelago, where there are several Galapagos natives we’ve yet to meet. Fed by the Cromwell Current, conditions here are much chillier than in the north. Divers are bellyaching before we even touch the 60-degree water, but the unique critters more than make up for the cold.

While the sun is still rising over Fernandina Island, we drop down to 80 feet at Cabo Douglas, an alien world decorated with colorful macroalgae, corals and neon-orange Mexican anemones. Redlipped batfish roam the sand flats, waddling across the bottom on uniquely adapted fins. Equally odd-looking are Galapagos sea robins that sift through the sand with their lobsterlike appendages while showing off their flashy wing fins.

Our next dive takes us closer to shore, where we wait among giant sea turtles and Galapagos fur seals for another of the islands’ iconic creatures—the Galapagos marine iguana. These endemic reptiles can be found throughout the islands, including the docks at Puerto Villamil, where I carefully picked my steps around dozens of lounging lizards sunning themselves on the walkway.

At first, they come one by one, but soon there are enough iguanas diving around us that you need to keep your head on a swivel to keep track of them all. Wave action is strong, as we’re no deeper than 30 feet, but the lizards’ powerful tails propel them through the surge with ease. When they reach the bottom, they pull themselves along the seafloor, timing their movements with the ebb and flow of the waves in a graceful display at odds with their clumsy terrestrial scuttling.

The world’s only seafaring lizard, marine iguanas are an extreme example of adaptation. When their ancient ancestors first washed ashore on Galapagos, the barren volcanic landscape offered little vegetation—submarine algae was the only source of food. The largest iguanas can dive to almost 100 feet, but most red and green algae is found in the shallows. Once an iguana begins to graze, that’s the best time to get a closer look.

Punta Vicente Roca, off the northern tip of Isabela, offers the greatest diversity yet. This is one of the most reliable spots to find mola mola. Our first dive takes us deep below the thermocline. Prepared to wait an agonizing 15 minutes in the cold, we are pleasantly surprised when one swims by as soon as the last diver hits 80 feet. Groups of three and then four pass us by. Their enormous, awkward bodies move surprisingly fast, and they disappear as quickly as they came. And so do we, rising into the warmer surface water to look for octopuses, giant seahorses and Galapagos bullhead sharks. A diving flightless cormorant shoots past at 60 feet and continues until it’s out of view.

I keep throwing a glance over my shoulder, hoping to catch sight of a Galapagos penguin—I’ve seen several topside and am dying to dive with them.

“There is a good chance we will see penguins,” Torres explained before the dive.

“But chance to see them and chance to catch them with your camera are different things. They are so fast in the water.” While I don’t see any during the dive, I capture some images of the sea lions that keep giving us a flyby every few minutes.

When we finally ascend after the second dive, we get one last surprise: a mola mola flashing its fin at the surface.

The Jungle Cruise

Los Tuneles, an intricate maze of lava rock off the coast of Isabela, was once a prime fishing spot. Today those fishermen maneuver tour boats between rocky pinnacles—a task made more challenging by tourists jumping between starboard and port for the best view. At every turn animals—many found nowhere else— perform as if on cue, tableaus straight out of an episode of Planet Earth.

We pass a penguin stoically posing on a rocky outcrop with seals on either side. On the opposite side of the boat, a Galapagos sea lion clambers out to survey our passing.

Blue-footed boobies feed their precious chick so close you could almost touch them, while a gigantic sea turtle grazes just below the glassy surface of the water.

Like most moments in the Galapagos, our little speedboat safari feels too good to be true, something you’d expect on the Jungle Cruise ride at Disney World. But instead of relying on advanced animatronics and painstakingly choreographed timing to create the illusion of life, the magic here is the genuine article.

Robby MyersGet off the grid in Galapagos with a hike up the Sierra Negra volcano on Isabela Island.

ISLAND HOPPING

Looking to do some terrestrial sightseeing before or after your cruise? Each of the main inhabited islands has something to offer.

San Cristóbal

Puerto Baquerizo Moreno is the capital of Galapagos and home to a large sea lion colony. It has several beaches, such as La Lobería, Playa Mann and Playa Punta Carola, that are popular with surfers, beachgoers and sea lions alike. Hike up Cerro Tijeretas to see nesting frigate birds and catch an amazing view across the island.

Bird-watchers shouldn’t pass up a day trip to Española Island, where they can see nesting waved albatrosses, blue-footed and Nazca boobies, Española mockingbirds and Galapagos hawks.

Santa Cruz

The bustling burg of Puerto Ayora is a hub for many tour operators and provides transportation to all of the inhabited islands. Nearby islands of North Seymour and Santa Fe are home to nesting seabirds, endemic land iguanas and wonderful snorkeling opportunities.

Day trips to Floreana, the smallest inhabited island and home to the oldest human settlement in Galapagos, are also available. Several geological features, such as lava tunnels and the Los Gemelos sinkholes, can be explored without a guide.

Isabela

Puerto Villamil is a quiet, remote town perfect for getting off the grid. Snoozing sea lions amicably share the beautiful, expansive beach with sunbathers, and wild flamingos can be found in the mangroves outside of town. A guided hike up the Sierra Negra volcano allows you to trek back in time through the geological history of Galapagos and maybe even spot a Galapagos hawk or the rare vermilion flycatcher. Snorkel excursions to Los Tuneles and Las Tintoreras get you in the water with seahorses, whitetip sharks and sea turtles and allow for up-close viewing of Galapagos penguins and blue-footed boobies.

Robby MyersGalapagos Aggressor III

NEED TO KNOW

When to Go

The dry season runs June through November and is the best time to see whale sharks at Darwin’s Arch. Diving is available year-round, with warmer water temperatures between January and May. Many species breed and congregate at different times throughout the year. If you are interested in a specific animal, research its behavior and plan accordingly.

Getting There

There are no direct flights to Galapagos; you must take an Ecuadorian domestic flight from either Guayaquil or Quito. Ninety-seven percent of the islands are under the protection of the Galapagos National Park; airlines follow strict biological controls— including fumigating passenger compartments midflight— to limit the risk of invasive species. Additional security includes a required transit control card prior to your flight and a bio-scan for your luggage. Be prepared to pay the $20 transit fee in cash at the airport and another $100 fee after your arrival. These fees fund the national park.

Dive Conditions

Conditions can vary throughout Galapagos, but strong currents, surge, thermoclines and cold water are all common. Most dives are between 50 and 70 feet. Water temperatures during the colder months range from the high 50s to mid-70s, bumping up about 10 degrees on either end between January and May. Many dives involve holding onto barnacle-covered rock—bring gloves.

Suggested Training

Advanced Open Water Diver; experience diving in currents and surge.

Operator

Diving is available throughout Galapagos, with land-based operators running day trips around Puerto Ayora, Puerto Baquerizo Moreno and Puerto Villamil and their neighboring islands. Darwin and Wolf, the crown jewels of Galapagos diving, are too remote for dayboats and are the sole domain of liveaboard operators. Aggressor Adventures operates Galapagos Aggressor III, a 100- foot yacht with a 22-foot beam; eight staterooms accommodate 16 divers attended by nine staff.

Price Tag

Deluxe staterooms aboard Galapagos Aggressor III start at $6,595 per person. Not including port, national park and visa fees. Daily two-tank dive trips from landbased operators start around $200.

MORE

• The Ultimate Galapagos Liveaboard Adventure

• Can we Save the Hammerheads of Galapagos