Scuba Equipment Issues Get This Diver in Deep Trouble

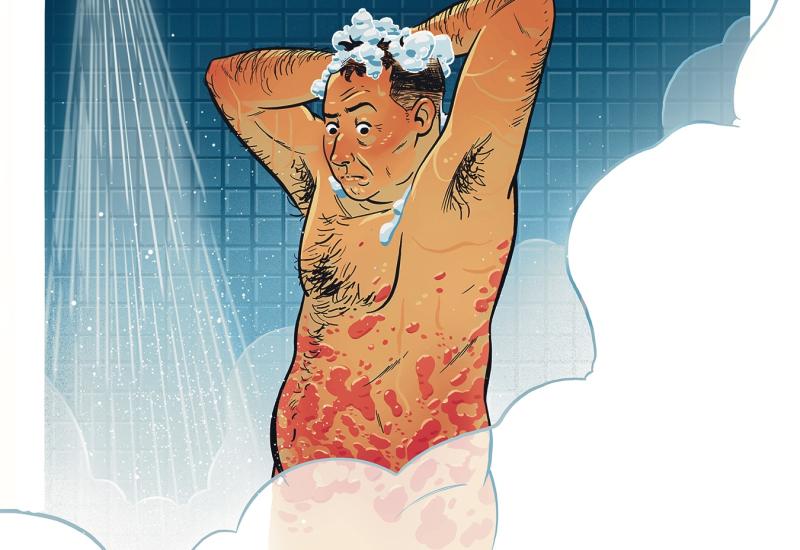

Carlo GiambarresiLack of familiarity with his drysuit costs a diver his life.

The water was too cold to dive in his wetsuit, but Eli wasn’t about to miss the chance to make this dive. He had heard stories and seen photographs of the nearly pristine wreck for years — when his chance came, he jumped at it. He just couldn’t seem to get his buoyancy under control in this rented drysuit.

Eli kept adding air to his suit and his BC, and then deflating both, but he continued to struggle. He kept feeling the air inside the suit move toward his feet, and then struggled to get trimmed out again.

The diver

At 39, Eli had been diving for about 10 years. He had made nearly 200 dives in his career, but most were in the Caribbean. Before this dive, he had made only two dives in a drysuit, each in a controlled situation in a local quarry.

The dive

Eli and his buddy made a shore entry and swam on the surface to get to the dive site. The water was cold and each diver was wearing a drysuit, although neither had formal training in its use. Their only previous experience wearing a drysuit was using them under supervision during a “try a drysuit” event at the local quarry. For this dive, they both rented suits from their local dive shop.

The location was a deep freshwater river, and there was current on the site. There was also some surface chop stirred up by the wind. The water temperature for this dive was much lower than on their previous dives in the quarry, so both divers were wearing thicker undergarments for insulation than they had used previously. Not being familiar with their suits, they guessed at the proper amount of weight they should wear for the dive.

The two divers swam 50 yards on the surface until they reached a descent line attached to the shipwreck. Once they were ready, both divers began the dive. The wreck rested in approximately 90 feet of water.

The accident

While on the wreck, the two divers became separated because of the current and poor visibility. Witnesses on the surface said Eli made an uncontrolled ascent to the surface, coming out of the water to his waist. He wasn’t on the surface for long, and didn’t seem to be conscious, before he descended again. No one on the surface was able to get to him in time.

When his body was found later that morning by two other divers, 40 feet underwater with his regulator out of his mouth, they were unable to inflate his BC because his tank was empty. They eventually dragged his body to shore and attempted to resuscitate him, but those efforts were unsuccessful.

Not long after Eli disappeared, his buddy returned to the surface alone.

Analysis

A check of Eli’s dive computer showed that he made a dive with a maximum depth of 88 feet with a total dive time of 35 minutes. The stored dive information showed a sawtooth profile where Eli bounced up and down, attempting to gain control of his buoyancy.

The official cause of death in this case was drowning due to insufficient air. Ultimately, that is accurate. He ran out of air while underwater and drowned. But like most dive accidents, there are many steps leading to the accident that are triggers to the final cause of death.

Eli was unfamiliar with his drysuit. It is certainly possible to rent an appropriately sized and fitted suit, but we do not know the condition of this suit. We do know, from his buddy, that Eli struggled with the suit underwater. Investigators afterward determined he was wearing more weight than necessary based on the conditions and his equipment.

He had made a couple of practice dives in a quarry but then changed his gear configuration by adding heavier undergarments to the suit. He guessed at the amount of weight he should be wearing and did not perform a buoyancy check before he began the dive.

We know from his dive buddy that the two divers became separated underwater and from witnesses on the surface that Eli made a rapid, uncontrolled ascent. If Eli lost control of his buoyancy and failed to exhale adequately while he ascended, it is possible he suffered an air embolism and lost consciousness.

An air embolism happens when air in the lungs expands rapidly during ascent, tearing a hole in the alveoli of the lungs and sending an air bubble into the arterial blood supply. The air bubble moves to the brain, causing strokelike symptoms. This is why divers learn to exhale continuously and never hold their breath.

If this scenario is accurate, the fact that Eli’s tank was empty when his body was recovered indicates that he kept his regulator in his mouth while unconscious and breathed his tank empty, only then drowning.

An alternative is that Eli ran out of air at depth. Distracted by his buoyancy struggles, he wasn’t aware he was running low. When he couldn’t take a breath, he bolted for the surface in a panic. An embolism is still likely in this scenario, causing him to lose consciousness and sink back underwater. In this scenario, unconscious, he lost his regulator and drowned.

This scenario is possible based on the length of his dive and his struggles with his buoyancy. During the dive, he continually added air to his drysuit and his BC, and repeatedly vented them both. He was also breathing heavily from a long surface swim in current while carrying too much weight. These factors could easily explain Eli’s using his air supply more quickly than anticipated. In this scenario, failure to monitor his air supply, brought on by his struggles with the drysuit, could be the trigger that led to the drowning.

It is rare that dive equipment fails and causes an accident. More often, it is the failure to use the equipment properly that is the problem. A drysuit, like anything else, is a tremendous tool, opening a world of diving in cold-water environments. In fact, many drysuit divers prefer them, wearing them in warmer water where most divers switch to wetsuits. The key is learning to use them properly.

Drysuits take practice and instruction to learn how to fit and use properly. You should also learn how to deal with an emergency underwater if you do lose control of your buoyancy.

On another note, Eli had made a couple hundred dives, but very few of them were in cold-water environments. Experience in one situation doesn’t necessarily carry over to another. He was used to diving in warm salt water with little or no exposure protection.

An experienced diver, he was a relative novice in this situation. Sometimes, as divers, we allow our comfort and familiarity to get the better of us, rather than asking for help or seeking training when things change.

Lessons for life

- Seek training with equipment: Any time you make a gear-configuration change, especially when it is significantly different from your personal experience, seek training. Don’t just assume you can figure it out.

- Perform a buoyancy check: When you change your gear configuration, don different exposure protection or change diving environments, take a couple of minutes to perform a buoyancy check to make sure your weight is correct.

- Monitor your air supply: It’s easy to become distracted on a dive, by equipment, photography or simply the beauty of the scene. But don’t forget your fundamentals. This also goes for never holding your breath.

- Experience in the environment, not just experience: Too often divers become overconfident with their personal experience but fail to realize a couple hundred dives in a lake doesn’t qualify them for a shore entry through ocean surf. Or dives in warm clear water don’t carry over to dark cold water on a shipwreck. Seek local advice or guidance in an unfamiliar environment.

About Lessons for Life

We're often asked if the Lessons for Life columns are based on real-life events. The answer is yes, they are. The names and locations have been removed or altered to protect identities, but these stories are meant to teach you who to handle a scuba diving emergency by learning from the mistakes other divers have made. Author Eric Douglas takes creative license on occasion for the story, but the events and, often, the communication between divers before the accident are entirely based on incident reports. Read more here.