The Ultimate Lessons For Life

(Insert diver's name) struggles to reach the surface as he verges on panic. With his air supply exhausted, he pulls hard on the regulator, but gets no air at all. At the surface, he throws off his mask as he struggles to stay afloat, forgetting to release his weight belt or inflate his BC. With a feeble yell for help, (Insert diver's name) slips beneath the surface ...

While each case we bring you in "Lessons for Life" is real, unique and thoroughly researched, the sad fact is that, in many cases, we could probably use a template similar to this one and still cover the basics. Month after month, season after season, and in case after case, the diving accidents we review and analyze often share similar causes and patterns.

Diving accidents are often predictable-and therefore avoidable-if divers and dive professionals use their common sense and basic dive training. When I interview dive accident survivors, someone usually makes reference to something that went wrong early in the dive or prior to the dive, yet no one dealt with the problem effectively. In hindsight, there is almost always an obvious window of opportunity to save a diver's life or prevent serious injury. Our mission in analyzing dives gone wrong is to help you develop the foresight to spot these and take the appropriate action to avoid becoming the next victim profiled in this column.

Rather than dissect a specific case this month, it seemed appropriate to step back and examine some of the broader lessons we've seen over the years in order to develop some common-sense guidelines to help you be a safer, more confident diver. Here then, are my ultimate lessons for life.

Don't Panic

People often ask me, "What one thing kills divers?" The answer is simple: Panic. Looking back on case after case, the difference between an accident that results in a fatality or serious injury, and one where the victim lives to dive again another day, is usually how well the diver controls panic. A healthy, well-trained diver can recover from even the most serious mishaps provided he remains calm and in control.

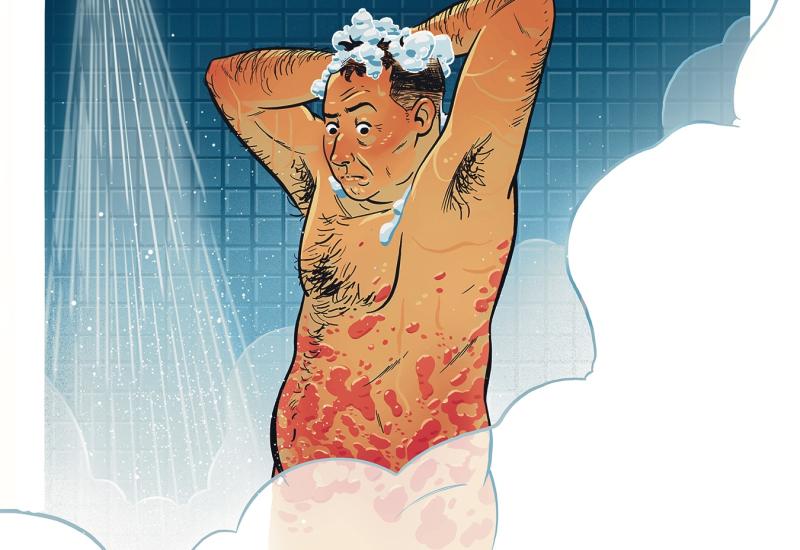

There is no one cause of panic. Panic usually stems from many small problems that grow and cascade to overwhelm the diver. Think of it this way: Divers operate like most people in everyday life-within a little bubble, typically referred to as a comfort zone. The closer to the edge of the bubble you get, the more likely you are to bump into its side and cause it to burst. On a perfect dive, when everything goes right, you remain in the center of your comfort zone. Add a little leak in your mask, and you move away from center. Add a current that is stronger than you expected, and you move a little further. If you're out of shape, you might move right to the edge.

The closer to the edge you get, the greater the odds that the next small problem will cause a diver to lose all control. When full-scale panic erupts, rational thought is replaced by reflexive reactions that frequently have no positive impact on the situation. Without outside intervention, a panicked diver will usually seriously injure himself or die from simply failing to take basic steps that could have fixed the problem. Common mistakes panicked divers make include discarding their regulator, removing their mask, not inflating their BC at the surface, and not ditching their weights.

Watch out for Murphy

Murphy, of Murphy's Law fame ("Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong"), is alive and well, and he lives in your gear bag where he patiently waits for opportunities to kill you. Poor dive planning, inadequate training and poorly maintained gear are invitations for Murphy to come out and wreak havoc. Deny him the opportunity to ruin your dive through careful advance preparation, by keeping your skills up to date and by keeping your gear properly maintained. Failure to do one or all of these things is usually a contributing factor in most of the dive accidents covered in this column.

Practice survival

Most victims in "Lessons for Life" enter the water completely oblivious to the potential for a dive accident, and therefore have no plan for dealing with the situation when things start to go wrong.

The strategy for smarter, safer diving is to routinely practice the basic safety skills learned in your open-water class, so if you have to respond to an emergency, they are second nature. It also helps to play the "what if" game with yourself and your dive buddies. Think about the things that could potentially happen on a specific dive and, more important, think about and practice ways to counteract or to respond to them. If you're diving in current, how will you adjust your dive? What will you do if you become separated from your buddy? What will you do if you surface down current from the boat? Are you carrying signaling devices? Do they work? How will you deploy them?

Fix the little things

If you enter the water with a problem, no matter how small, that problem is not going to go away or get better on its own. In fact, it's just the opposite. Minor annoyances can pile up to become critical problems as the dive progresses.

If your dive does not start out well, you need to identify the problem and solve it immediately, or abort the dive. Your leaking mask may simply be due to a misplaced seal, but it could also be a tear in the skirt. It is best to find out at 10 feet on the anchor line than it is to discover it at 100 feet down and 200 yards from the boat.

Listen to the briefings

I have logged well in excess of 5,000 safe dives and I still take time to listen to the details of every dive briefing, and I pay especially close attention on any site I do not know well. You pay diving professionals for their skill, expertise and local knowledge of diving conditions. They know the hazards, the site specifics, and the points of interest that make your dives both safer and more enjoyable. Even on sites where I have logged dozens of dives over the years, I take the time to listen carefully. Conditions change, current patterns shift and there can be changes in the marine life. The local diving professional who dives these sites daily is the expert, so use him to avoid getting yourself into unexpected situations that can lead to diving accidents.

This rule also applies to the boat briefing, a source of invaluable information on the procedures the crew will use in both normal circumstances and in cases of emergency. Pay close attention and should things go wrong, you'll be able to work in harmony with the crew to set them right as quickly as possible. You may recall a recent column (case No. 101) where a very experienced diver chose to ignore the boat crew's advice on the safest procedure for donning equipment and entering the water. He ended up unconscious and bleeding from the head when he slipped and fell as a result of his arrogance.

Get the Right Safety Gear

As a dive store owner, I love the diver who buys every single trinket that I sell. However, it is preferable that he not try to dive with all of them at once. Too much equipment-even if it's safety gear-can throw off your buoyancy and trim and create danglies that invite entanglement.

It's relatively easy for every diver to carry redundant safety gear without a lot of hassle or bulk. I always carry a large, brightly colored inflatable surface marker, a dive light and a sonic alert device on every dive in open water. As a rule of thumb, it's also a good idea for every diver to carry a dive knife with a small backup pair of shears tucked neatly into a pocket and an old-fashioned whistle as a backup to an air-powered sonic alert device.

Make sure that every piece of gear you're carrying is in good working order and properly stowed before the dive. Think carefully about placement of each item. You want to stay streamlined and eliminate entanglement hazards, but you also need to be able to locate and deploy each item quickly and easily.

Take responsibility for your own safety

You are responsible for you. No one can swim for you, think for you, plan for you, and nobody can save your life when you fail to prepare-only you can do all this. Never trust anyone else to keep you safe. Take responsibility for your own actions and be prepared to deal with your own problems, including assisting your buddy in an emergency.

I hope that the applications of these rules and the other safety tips in this magazine will keep you on the proper side of "Lessons for Life"-as a reader, not a subject. Safe diving!

(Insert diver's name) struggles to reach the surface as he verges on panic. With his air supply exhausted, he pulls hard on the regulator, but gets no air at all. At the surface, he throws off his mask as he struggles to stay afloat, forgetting to release his weight belt or inflate his BC. With a feeble yell for help, (Insert diver's name) slips beneath the surface ...

While each case we bring you in "Lessons for Life" is real, unique and thoroughly researched, the sad fact is that, in many cases, we could probably use a template similar to this one and still cover the basics. Month after month, season after season, and in case after case, the diving accidents we review and analyze often share similar causes and patterns.

Diving accidents are often predictable-and therefore avoidable-if divers and dive professionals use their common sense and basic dive training. When I interview dive accident survivors, someone usually makes reference to something that went wrong early in the dive or prior to the dive, yet no one dealt with the problem effectively. In hindsight, there is almost always an obvious window of opportunity to save a diver's life or prevent serious injury. Our mission in analyzing dives gone wrong is to help you develop the foresight to spot these and take the appropriate action to avoid becoming the next victim profiled in this column.

Rather than dissect a specific case this month, it seemed appropriate to step back and examine some of the broader lessons we've seen over the years in order to develop some common-sense guidelines to help you be a safer, more confident diver. Here then, are my ultimate lessons for life.

Don't Panic

People often ask me, "What one thing kills divers?" The answer is simple: Panic. Looking back on case after case, the difference between an accident that results in a fatality or serious injury, and one where the victim lives to dive again another day, is usually how well the diver controls panic. A healthy, well-trained diver can recover from even the most serious mishaps provided he remains calm and in control.

There is no one cause of panic. Panic usually stems from many small problems that grow and cascade to overwhelm the diver. Think of it this way: Divers operate like most people in everyday life-within a little bubble, typically referred to as a comfort zone. The closer to the edge of the bubble you get, the more likely you are to bump into its side and cause it to burst. On a perfect dive, when everything goes right, you remain in the center of your comfort zone. Add a little leak in your mask, and you move away from center. Add a current that is stronger than you expected, and you move a little further. If you're out of shape, you might move right to the edge.

The closer to the edge you get, the greater the odds that the next small problem will cause a diver to lose all control. When full-scale panic erupts, rational thought is replaced by reflexive reactions that frequently have no positive impact on the situation. Without outside intervention, a panicked diver will usually seriously injure himself or die from simply failing to take basic steps that could have fixed the problem. Common mistakes panicked divers make include discarding their regulator, removing their mask, not inflating their BC at the surface, and not ditching their weights.

Watch out for Murphy

Murphy, of Murphy's Law fame ("Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong"), is alive and well, and he lives in your gear bag where he patiently waits for opportunities to kill you. Poor dive planning, inadequate training and poorly maintained gear are invitations for Murphy to come out and wreak havoc. Deny him the opportunity to ruin your dive through careful advance preparation, by keeping your skills up to date and by keeping your gear properly maintained. Failure to do one or all of these things is usually a contributing factor in most of the dive accidents covered in this column.

Practice survival

Most victims in "Lessons for Life" enter the water completely oblivious to the potential for a dive accident, and therefore have no plan for dealing with the situation when things start to go wrong.

The strategy for smarter, safer diving is to routinely practice the basic safety skills learned in your open-water class, so if you have to respond to an emergency, they are second nature. It also helps to play the "what if" game with yourself and your dive buddies. Think about the things that could potentially happen on a specific dive and, more important, think about and practice ways to counteract or to respond to them. If you're diving in current, how will you adjust your dive? What will you do if you become separated from your buddy? What will you do if you surface down current from the boat? Are you carrying signaling devices? Do they work? How will you deploy them?

Fix the little things

If you enter the water with a problem, no matter how small, that problem is not going to go away or get better on its own. In fact, it's just the opposite. Minor annoyances can pile up to become critical problems as the dive progresses.

If your dive does not start out well, you need to identify the problem and solve it immediately, or abort the dive. Your leaking mask may simply be due to a misplaced seal, but it could also be a tear in the skirt. It is best to find out at 10 feet on the anchor line than it is to discover it at 100 feet down and 200 yards from the boat.

Listen to the briefings

I have logged well in excess of 5,000 safe dives and I still take time to listen to the details of every dive briefing, and I pay especially close attention on any site I do not know well. You pay diving professionals for their skill, expertise and local knowledge of diving conditions. They know the hazards, the site specifics, and the points of interest that make your dives both safer and more enjoyable. Even on sites where I have logged dozens of dives over the years, I take the time to listen carefully. Conditions change, current patterns shift and there can be changes in the marine life. The local diving professional who dives these sites daily is the expert, so use him to avoid getting yourself into unexpected situations that can lead to diving accidents.

This rule also applies to the boat briefing, a source of invaluable information on the procedures the crew will use in both normal circumstances and in cases of emergency. Pay close attention and should things go wrong, you'll be able to work in harmony with the crew to set them right as quickly as possible. You may recall a recent column (case No. 101) where a very experienced diver chose to ignore the boat crew's advice on the safest procedure for donning equipment and entering the water. He ended up unconscious and bleeding from the head when he slipped and fell as a result of his arrogance.

Get the Right Safety Gear

As a dive store owner, I love the diver who buys every single trinket that I sell. However, it is preferable that he not try to dive with all of them at once. Too much equipment-even if it's safety gear-can throw off your buoyancy and trim and create danglies that invite entanglement.

It's relatively easy for every diver to carry redundant safety gear without a lot of hassle or bulk. I always carry a large, brightly colored inflatable surface marker, a dive light and a sonic alert device on every dive in open water. As a rule of thumb, it's also a good idea for every diver to carry a dive knife with a small backup pair of shears tucked neatly into a pocket and an old-fashioned whistle as a backup to an air-powered sonic alert device.

Make sure that every piece of gear you're carrying is in good working order and properly stowed before the dive. Think carefully about placement of each item. You want to stay streamlined and eliminate entanglement hazards, but you also need to be able to locate and deploy each item quickly and easily.

Take responsibility for your own safety

You are responsible for you. No one can swim for you, think for you, plan for you, and nobody can save your life when you fail to prepare-only you can do all this. Never trust anyone else to keep you safe. Take responsibility for your own actions and be prepared to deal with your own problems, including assisting your buddy in an emergency.

I hope that the applications of these rules and the other safety tips in this magazine will keep you on the proper side of "Lessons for Life"-as a reader, not a subject. Safe diving!