Two Scuba Divers Make All the Wrong Moves

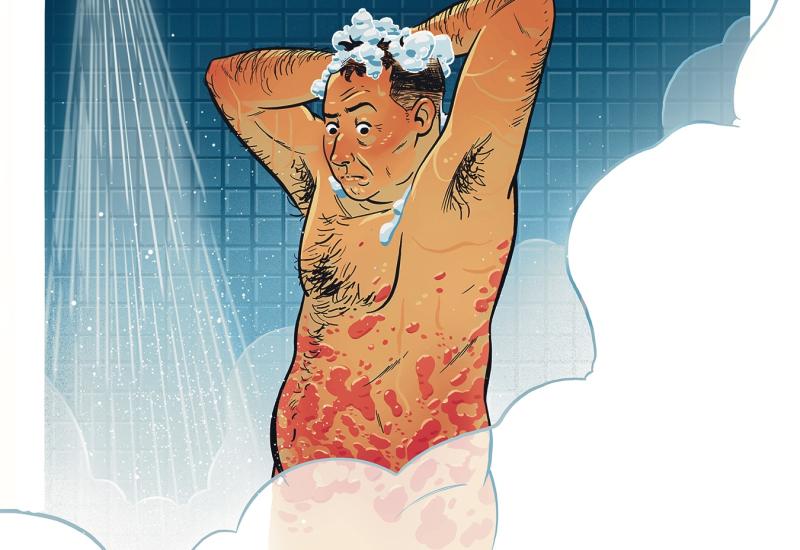

Carlo GiambarresiPanic is the root cause of many dive accidents. Even when the situation is set up by failed equipment, it is the diver’s reaction that causes the accident.

Jack and Diana were going spearfishing. Diana didn’t know what she was supposed to do, but Jack told her it was going to be “epic.” They were diving from Jack’s friend’s boat — his friend would wait for them on the surface.

Diana hadn’t been diving much, so she was a little uncomfortable with what Jack had planned, but she went along anyway. She wasn’t spearfishing. Jack had convinced her to be his buddy while he caught dinner for the three of them. She knew she was supposed to stay with Jack, but also to stay out of the way.

THE DIVERS

Jack was a 37-year-old male. He was certified but had only a few logged dives under his belt and hadn’t been in the water in the past year. Jack was overweight and described as “reckless” by divers who knew him. He was also known to use recreational drugs.

Diana was 35 and in fair health. She was a certified diver but had less experience than Jack and hadn’t been diving in more than a year.

Jack had gear for both divers in his garage, but it had not been touched since the last time he’d gone diving. He had two full tanks.

THE DIVE

Jack and Diana met his friend Dave in the early afternoon to go out on Dave’s boat and make the dive. Jack had convinced Dave that he could catch them fish for dinner and they could have a party that evening. Surface conditions were mild, but by all reports, there was a strong current in the area that day.

Jack grabbed gear and tanks, gave Diana what she needed, and they both geared up for the dive. Jack had to remind Diana how to assemble her gear. As soon as they had their gear on, both divers back-rolled into the water from the small craft.

Dave threw a weighted descent line into the water behind the boat, with a marker buoy on the surface to guide the divers to the line. He stayed behind to care for the boat and keep an eye out for the divers from the surface.

THE ACCIDENT

Moments after the two divers began their dive, Jack surfaced and waved to Dave for help. Diana followed Jack back to the surface, but Dave reported that both divers appeared to struggle to stay on the surface. Neither of them was in control of their actions. Not being a diver, Dave wasn’t in the best position to help his friends.

Both divers attempted to hang onto the buoy to keep their heads above water while they sorted out their problems. While they fought to get control, they became entangled in the descent line. Jack struggled to catch his breath. He grabbed Diana’s alternate air source to breathe from as they both descended below the surface.

Ditching your weights in an emergency is a basic skill. The only way to avoid panic is by practicing emergency skills to the point they become automatic.

Another boat arrived at the scene. Rescuers attempted to pull the two divers to the surface using the descent line. It broke, separating the marker buoy from the descent line. That was the only thing keeping the divers near the surface. The divers did not resurface.

A rescue dive team was called to the scene, and they recovered the bodies of both divers an hour later in 50 feet of seawater. Jack was still wearing his weights and was entangled in the descent line. Diana had dropped her weights, but she was also tangled in the descent line just a few feet above Jack. Her mask was on her forehead. Both divers had nearly full air tanks.

Jack’s autopsy indicated he had drowned. A toxicology report was positive for cocaine use, along with antihistamines and cold medicine. The accident analysis showed his dive gear was nearly unusable, and his BC would not hold air.

Diana’s autopsy also indicated she drowned and had cocaine in her system. Her equipment was in only slightly better condition than Jack’s.

ANALYSIS

Both divers in this case died of drowning due to entanglement while scuba diving. It’s not uncommon in panic situations for divers to spit out their regulators. They drowned with air in their tanks.

The real causes of the accident, though, are lack of preparation, poor planning, lack of recent experience, and poorly maintained equipment. We don’t know when they each used cocaine, whether it was the day of the accident or the day before, but that isn’t a good indication either.

Ultimately, both divers entered the water with barely functional dive gear. When it didn’t work at depth, they began to panic. Since Jack surfaced first and then attempted to use Diana’s alternate air source on or near the surface, we can assume that Jack’s gear was not delivering air. His BC wouldn’t hold air, so he couldn’t stay on the surface to get himself under control.

Before the dive, both divers should have performed a quick buddy check to make sure their gear was working properly. If they had, Jack likely would have realized his regulator wasn’t working properly and his BC would not hold air.

Panic is the root cause of many dive accidents. Even when the situation is set up by failed equipment, it is the diver’s reaction that causes the accident.

Even in this situation, if Jack had realized his regulator wasn’t delivering enough air and simply swam back to the surface, both divers could have survived. If he couldn’t swim upward because he was overweighted and his BC would not hold air, all he had to do was drop his weights and make the swim. He didn’t respond that way, and panic quickly took hold.

Ditching your weights in an emergency is a basic skill. The only way to avoid panic is by practicing emergency skills to the point they become automatic. You could make the case that this dive accident happened because two unprepared divers got in the water without adequate gear, and you would be right. But we can all still learn something from this accident, and it goes back to the basics.

Diana wasn’t comfortable with the dive, but she went along anyway. She didn’t have recent experience in the water, so she should have taken a refresher dive to practice her skills and familiarity with her equipment in a controlled environment. Jack hadn’t dived in more than a year either. His gear hadn’t been serviced, or even touched, since his last dive.

Before the dive, both divers should have performed a quick buddy check to make sure their gear was working properly. If they had, Jack likely would have realized his regulator wasn’t working properly and his BC would not hold air.

These basics are taught and tested in open-water dive classes, but many divers haven’t practiced emergency skills such as mask removal and replacement, regulator recovery or breathing from an alternate air source since the day they finished their class and earned their certification card.

Equipment malfunctions are rare when the equipment has been maintained properly. Too many dive accidents happen when divers aren’t prepared for the dive and do not know how to respond to an emergency when it arises.

Lessons for life

■ Practice emergency skills. A safety stop is a great time to run through drills. Just warn your dive buddies first.

■ Maintain gear properly. Dive gear is incredibly reliable, but it is life-support equipment and should be treated as such.

■ Don’t make dives you aren’t prepared for. Any diver can call any dive for any reason. That needs to be your motto. If you aren’t comfortable with a situation or feel something is off, figure out the problem or get more training before you make the dive.

■ Do a buddy check to make sure everything works. Too often, experienced divers skip this step before they get in the water. It takes only a few seconds but can solve a lot of problems.