World’s Largest Colony of Fish Nests Found Under Polar Ice

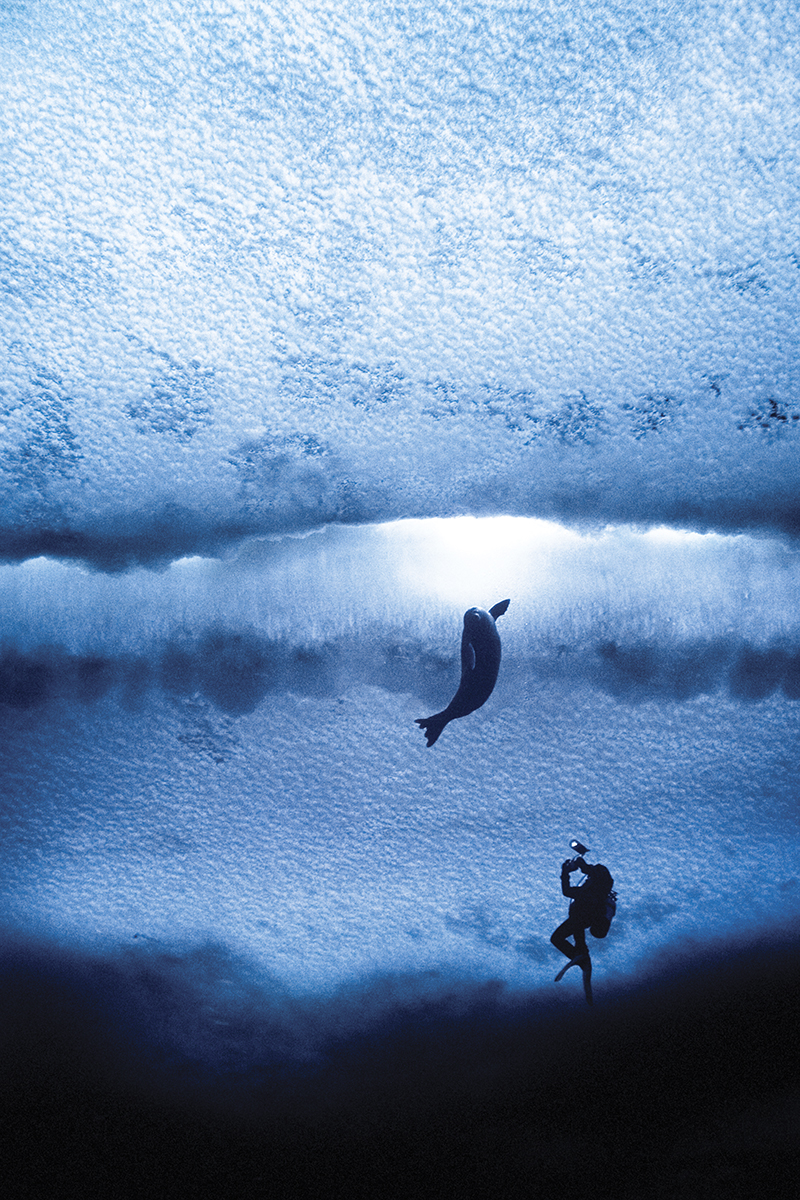

PS118, AWI OFOBS teamIcefish nests in the Weddel Sea.

Sixty million icefish nests spread across more than 90 square miles was recently discovered over 1,600 feet below the ice in Antarctica’s Weddell Sea, the largest fish nesting aggregation ever discovered.

Scientists have previously seen several dozen icefish nests at a time. Before this discovery, most social of nesting fish species were thought to gather in the hundreds, not tens of millions. Scientists now theorize that icefish has a much larger influence on the Antarctic food web than ever previously believed, researchers report in the journal Current Biology.

A team of deep-sea biologists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute found the nests last year while conducting research on the chemical connections between surface water and the ocean floor using a camera towed slowly behind their research vessel.

When recording footage below the Weddell Sea’s Filchner ice shelf, the camera operator kept coming across Jonah’s icefish nests.

“When I came down half an hour later and just saw nest after nest the whole four hours of the first dive, I thought we were onto something unusual,” Autun Purser, head of the team, tells Science News.

An additional three surveys in the area discovered similarly spaced Jonah’s icefish nests for nearly 100 miles.

Evolutionary biologist Thomas Desvignes of the University of Oregon, who was not involved in the research, tells Science News the massive colony is an “amazing discovery” — especially the fact that the nests were so close together.

“It made me think of bird nests,” Desvignes says. “When we see cormorants and other marine birds that nest like that, one next to the other — it’s almost like that.”

Icefish have many unique adaptations that allow them to survive in the extreme cold, like clear blood that contains antifreeze compounds. But scientists are unsure of why they’re gathering to breed.

One theory is the availability of plankton in the area provides plentiful food when the fish first hatch. There was also a zone in the area that had slightly warmer water, which may help icefish find the breeding ground.

Purser suspects there may be smaller colonies of Jonah’s icefish nearer to the shore, but if there aren’t any — if all of the eggs really are concentrated under one ice shelf — it could spell trouble for the future of the species.

This "would make the species extremely vulnerable," Desvignes says

Purser’s team has installed two seafloor cameras at the site, which will remain stationary for a couple of years, taking four photos per day to see if the fish reuse nests and find out more information about this unique breeding ground.

“I would say [the colony] is almost a new seafloor ecosystem type,” Purser says. “It’s really surprising that it has never been seen before.”