Life Under Foot: Diving Under Piers and Bridges

If you think you need to scour the world in search of remote pinnacles, lonely outposts and uninhabited islands to find the best diving, think again. Some of the best diving spots on the planet are literally under your feet: Piers and jetties — man-made wonders of a practical nature — have transformed into thriving marine kingdoms. From Washington state’s Keystone Jetty and Florida’s Blue Heron Bridge to the Samarai Wharf of Papua New Guinea, these are seven of the most dynamic jetty dives in the world.

Blue Heron Bridge, Florida

It might not be a jetty in the strictest sense (though it is used to tie up boats), but Florida’s best shore dive is one of those can’t-wait-to-get-under experiences rendered all the more surprising by its incongruous topside surrounds — a rushing overpass, South Florida’s ubiquitous looming condoscape and even a power plant off in the distance. Once you’re submerged at the Blue Heron Bridge, an intoxicating universe of critters is the only view worth considering.

The area surrounding the bridge is constantly fed and renewed by the flow of nutrients sloshing in from the Atlantic, which has brought in an explosion of life that calls this stretch of the Intracoastal Waterway between Palm Beach and Singer Island home. The Little Blue Heron Bridge, the bridge’s easternmost stretch, is under construction until late 2011, so you can’t get under it for now. But divers can still scope the south side for a chance to see striated and hairy frogfishes and longsnout seahorses that are in abundance. Another prime spot for seeing frogfish is along the mooring ball lines of sailboats that have been berthed near the small beach.

As you float over the rubble bottom, look for sea robins and red-lipped batfish. Bristle worms, urchins and pincushion starfish abound. And it’s worth training your macro vision for surprises like bumblebee shrimp, sometimes spotted going for a starfish stroll. A rustle in the sand could be anything: a peacock flounder, perhaps, or a spooked razorfish. Octopuses are omnipresent, but you have to know where to look — they are often seen in discarded bottles that have escaped divers’ cleanup efforts.

On the main stretch of the eastern Blue Heron Bridge, wooden fenders appear to have been painted by a crayon-crazed kid with a penchant for clashing colors — orange soft corals and sponges and purple barrel sponges carpet the scene. Seaweed blennies peek curiously from their barrel burrows, while off in the deeper water, Bermuda chubs school. You’ll probably see hogfish and stoplight parrotfish here too at depths that don’t pass 16 feet (the rest of the dive barely dips below the 10-foot mark). It’s loads of bottom time for observing curious behaviors that often get lost in the larger dive fray. — Terry Ward

Make It Happen

Grab a parking spot at Phil Foster Park in Riviera Beach on the north side of the bridge, and plan your dive for the two-hour window either side of high tide. Make a day of it by heading out on a charter with Walker’s Dive Charters (www.walkersdivecharters.com), and you’ll get to dive one of the thriving nearby reefs or wrecks while waiting for the bridge’s tidal window (a two-tank dive costs $70 per person). Water temperatures range from the mid-80s in the summer months to the 70s and 60s in the winter, and visibility is usually between 50 and 80 feet (though up to 100 feet is possible).

Samarai Wharf, PNG

Colonized in the 1880s, Samarai Island was once the largest town in Papua and a magnet for “Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits.” Eventually Port Moresby became the center for government, and Samarai was virtually abandoned, leaving behind a succession of wharves built to accommodate visiting missionary boats, pearling and gold-prospecting luggers, international steamships and government launches.

The eastern section of the wharf still stands; the middle section was demolished and the west section left to fall apart. A pearl farm — gallantly breeding gold lip pearl shell in a bio-clean room inside an ancient warehouse — has brought back enterprise, and happy greetings are the rule from the friendly inhabitants. But Samarai is a shadow of its former glory.

Except underwater. Here it has never been better.

Caressed by the notorious tidal currents of the China Strait, the wharf piles are havens for a miraculous multitude of marine creatures. Yellow tubastraea corals, polyps blooming even in daytime, provide a golden-yellow backdrop to swirling baitfish, batfish, convictfish, catfish and angelfish — including the elsewhere-rare black Samarai angelfish, now named after Tawali Dive Resort operator Rob Vanderloos. A wobbegong shark is usually resting in the shade of the wharf along with scorpionfish, stonefish, toadfish, crocodilefish and octopuses.

Divers wanting a change from critter hunting can scavenge for torpedo and marble-stoppered bottles from the 1890s. Poorly blown, with imbedded bubbles, the most sought after is the marble bottle marked “Patchings — Samarai” made especially for the soda factory on the island. Current-scoured sand gutters off the wharf are good places to search for old bottles. Lively reef patches edge the gutters where resident lionfish, damsels and featherstars hide the lairs of mantis shrimp. A rusty, overgrown anchor juts out from the seabed, an unusual maroon-colored sea star snuggling a fluke.

Care needs to be taken to avoid fishing-line snares and sharp-edged clams, and a Port Moresby tide chart is useful to predict Samarai slack current — two hours before and four hours after high tide in Moresby. And you might very well use all those six hours —with a maximum depth of just 40 feet, you could be exploring the Samarai Wharf for a long time. — Bob Halstead

Make It Happen

Samarai is one hour by speedboat from the Milne Bay provincial capital of Alotau. Diving is year-round, as the site is sheltered (as most wharves are!). Water temperatures vary from 79 degrees F in the winter (July and August) to 84 degrees F in the summer. Visibility ranges from 30 to 60 feet. Live-aboards MV Golden Dawn, FeBrina, Chertan and Spirit of Niugini occasionally include Samarai on their itineraries. Tawali Dive Resort (www.tawali.com) offers day trips to Samarai for its guests. A six-night, 15-dive package at Tawali starts at $1,912 per person. Per night rates for the live-aboards run from $285 (Chertan), $340 to $360 (Spirit of Niugini), $395 (FeBrina) and $350 to $400 (Golden Dawn). Small speedboats use the wharf area, so take caution if surfacing away from dive boat. The dive flag is not recognized by villagers, so it’s best to surface right at the dive boat or tender.

Cendana Pearl Farm Pier, Raja Ampat, Indonesia

Dropping down into the shady parts under Alyui Bay’s Cendana Pearl Farm Pier in Raja Ampat, it’s apparent that marine life is at its most robust here. Sunlight sparkles along the edges of the main platform and peeks through the wooden slats to create striking light beams, but most fish and invertebrates prefer the dim confines beneath the pier.

Ignoring divers, well-fed stonefish show their grumpy-looking countenances next to matching mounds of living rock. With incessant currents carrying plankton to the waiting mouths of filter feeders, the stonefish barely have to move in order to feed on large numbers of unsuspecting cardinalfish, damsels or gobies. Not far away, a pair of banded pipefish poke their slender snouts out from crevices, a juvenile crocodilefish mimics a drowned tree branch and a juvenile cuttlefish camouflages itself amid crinoids and sponges. Tear your gaze away from the life on the critter-laden bottom and look upward, where you’ll see a massive school of scad form a silver river of fish slipping between the pier pilings. Onlookers from above, longfin spadefish hover over the scad, watching the parade.

Located near the mouth of the Alyui Bay on the western edge of Waigeo Island, the pearl farm is swept by healthy, nutrient-rich waters that allow prolific marine growth, especially under its main pier. The bay is a large maze of forested islands, limestone islets, thick mangroves and narrow channels that serve as nurseries, reproductive sites and feeding grounds for thousands of marine species. A number of excellent dive sites for both critters and wide-angle scenery are found throughout the area, minutes from any anchorage. Though several nearby channels can provide exhilarating drifts, the Cendana Pier consistently offers light currents and profuse life that is difficult to match.

Every other dive under the pier turns up a resident tasseled wobbegong, which evidently appreciates the abundance of food associated with the pier. Another shark often found amid the mushroom leather corals growing along the pier is the Raja epaulette shark, one of the region’s unusual endemics. The pier, its pilings and surrounding habitat are absolutely loaded with the bizarre creatures that divers have a special affinity for, from tiny shrimp, frogfish and waspfish to sweeping scenes of reef diversity. Dappled by light and shadows, sponges, soft corals, gorgonians, bivalves and delicate tunicates clutter the site with dreamlike scenery, which is as good as it gets no matter what divers are in search of. — Ethan Daniels

Make It Happen

With a number of interesting dive sites, Alyui Bay is a common stop for live-aboards exploring Raja Ampat’s northern islands. Though the pier is used on a daily basis for loading and unloading pearl-farm equipment, it can be dived at almost any time of day or night with permission from the farm management. Water temperatures are fairly constant, ranging between 81 to 84 degrees F year-round, but visibility can vary from 40 to 70 feet depending on the tide and weather. Live-aboards can anchor within minutes of the pier and, due to it being fairly shallow (between 3 and 45 feet), divers can expect to stay under the dock for long periods. Eleven-night trips on board the Paradise Dancer start from $4,750.

Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier, Dominica

The payoff in diving Dominica’s Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier comes almost immediately. Shortnose batfish favor the sand-rubble bottom, and divemasters routinely point out these 5-inch walking oddities with noses that rival Cyrano de Bergerac’s. With pectoral and pelvic fins that resemble hands and feet, batfish actually “walk,” and will move clumsily away from divers, fluttering slightly above the bottom as they try to find a new place to hide under the pier.

The wooden pier — named Pole to Pole by local operators — is located on the island’s northwestern coast in Prince Rupert Bay. The bay is sheltered on its northern side by the Cabrits headland, a rugged, volcanic outcropping that juts from the mainland. There are terrific sites north of the Cabrits peninsula, but unpredictable strong currents and swells from the north can sometimes cancel the diving at less-protected places. In contrast, the pier offers calm conditions and reliable visibility in just 48 feet of water, day or night.

The pier’s legs are plastered with sponges — a profusion of finger, encrusting and tube sponges vie for real estate — and longsnout seahorses are tucked in between the mass of life. Batfish and seahorses aren’t the only creatures making a living under the pier. Comical-looking balloonfish hide in crevices. Jawfish poke their heads out from the safety of hiding places among the piles of small boulders and debris. Get even closer to spot yellowline arrow crabs gingerly high-stepping out of cracks, shy secretary blennies peeking from their tiny burrows and spotted cleaner and coral banded shrimp clinging to bottles that have become part of the underwater landscape. This is a place of refuge for peacock flounders, frogfish and juveniles of many reef species like blue and brown chromis, sergeant majors, gobies and barred hamlets.

Divers can spend all their bottom time finning from one pole to the next, but there’s also plenty to explore adjacent to the pier: Creatures like urchins and lobsters hide in the rocky boulders jumbled atop one another, and sand eels and flying gurnards are found in the sand flats. Muck diving can sound unappealing — the best muck sites are in shallow water with a fair bit of debris like discarded tires, engine parts and bottles strewn about — but savvy divers know these sites deliver a rich habitat populated by bizarre and colorful creatures. More commonly associated with Pacific destinations like Indonesia’s Lembeh Strait and Papua New Guinea’s Milne Bay, outstanding muck experiences can also be found in the Caribbean, often underneath piers like Pole to Pole. All divers need is a camera equipped with a macro lens — and an appreciation for the weird and wonderful. — Patricia Wuest

Make It Happen

The Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier is only occasionally used as a berth by cruise ships (most dock in Roseau on the southwestern end of the island). Pole to Pole can be dived from either shore or boat, day or night. Water temperatures range from 78 degrees F in winter to 83 degrees F in summer, and visibility is a dependable 50 to 60 feet, though it can be as good as 100 feet. Cabrits Dive Centre (www.cabritsdive.com) in Portsmouth puts divers in the water at the pier in less than 10 minutes from where its boat is docked. Two-tank guided boat dives start from $87.50 and one-tank night dives from $65.50. One of the owners is British, so tea and biscuits are often served on board. Brilliant.

Keystone Jetty, Washington

Part of Fort Casey State Park, Keystone Jetty operates as a ferry landing for bucolic Whidby Island in the Puget Sound. It’s a quick escape for the hard-core dive community in Seattle, and one of the top dives in the area, renowned for its biodiversity. It’s strictly shore diving and the deepest part of the dive is only about 55 feet, with some of the best stuff in the shallower parts.

There are actually two places to dive in this protected marine area: the old pier and the breakwall that protects the ferry landing. There are picnic tables, toilets and even a hot-water shower to help thaw you out after a dive in the average 50 degree F water.

But the encounters make it worth the effort to dive the jetty. Massive lingcod with heads the size of soccer balls sit and stare you down. Giant Pacific octopuses also call the jetty home and are found along the breakwall, and if you’re lucky, one of these playful critters will interact with you. Consider yourself warned, though: There are tales of these giant octopuses removing divers’ masks in a moment of curiosity, so stay alert around them.

The pilings of the pier are covered in anemones and, like most piers, harbor legions of macro critters including a variety of nudibranchs and invertebrates. Bull kelp adds a surreal aspect to the dive, punctuated by snow-white plumrose anemones. Perch, cabezon and giant barnacles also like the pier, and the omnipresent barnacles are a sign of one certainty about diving here in Puget Sound: current. It’s best to plan to dive at slack tide and explore slowly. Cold-water marine life tends to prefer stillness, so you could easily miss something if you’re off to the races. If you have a chance, dive the Keystone Jetty midweek, when you’ll have the site all to yourself. — Ty Sawyer

Make It Happen

Whidby is about 30 miles north of Seattle. You can drive in via the north side of the island, which takes you over Deception Pass and its scenic bridge, or take the Mukilteo Ferry, which leaves from the town of Everett. From the Whidby landing, it’s about a 26-mile drive. From Port Townsend, you can take the ferry directly to Keystone.

Frederiksted Pier, St. Croix

St. Croix’s Frederiksted Pier is a tale of two dives. The original pier was virtually destroyed by Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Most of the parts left standing were towed to another dive site, and a new Frederiksted Pier was built in its place. In just a few years, marine life has already taken hold, and together, the two piers have become one of the Caribbean’s hottest dive sites.

As you head out to the new pier, you’ll pass some pilings and “dolphins” from the old pier, as well as some scattered debris courtesy of Hugo. Don’t rush through the old section, though, as it’s a perfect hiding spot for seahorses, trunkfish, batfish and lots of moray eels.

It takes many divers many dives to get past the section that’s left from the original pier. But ignore the new pier at your peril — it ripples with the syncopated streams of baitfish that wind and spin around the pilings in the shallow water. Sponges are becoming increasingly prominent, and frogfish, batfish and seahorses have taken up residence along the new pier’s pylons.

If you have the time, make both a day dive and a night dive. Like all great pier dives, the Frederiksted Pier erupts at night. Several species of shrimp reveal themselves with shining eyes, and octopuses come out to patrol through the remains. The new pier also plays host to a number of topside activities, so check with the shops to see what might be going on during your night dive. For example, bands often play on the pier at night, so your dive might be accompanied by the not-so-distant sounds of steel drums. — Ty Sawyer

Make It Happen

The Frederiksted Pier is as famous as the beer-swilling pig at the Montpellier Domino Club. Every dive shop on the island will visit the site at least once during a typical week of diving; if you want to dive it more than once, arrange to do a shore dive.

Busselton Jetty, Western Australia

In a country with no shortage of outstanding jetty dives (including Exmouth Navy Pier, Rapid Bay Jetty and Edithburgh Jetty), Western Australia’s Busselton Jetty outshines them all. Standing on Busselton’s white-sand beach, the jetty seems to extend all the way to the horizon, where a cloudless Western Australian sky meets an equally blue Indian Ocean. In fact, at 6,040 feet long, picturesque Busselton Jetty is the longest wooden jetty in the southern hemisphere.

But it didn’t start out that way. Built in 1865 to service whaling and other types of vessels, the jetty’s original length was 518 feet. Seven extensions were added by the turn of the 20th century thanks to Western Australia’s booming resource trade.

Nowadays the jetty is a tourist attraction, drawing more than 400,000 visitors each year. And if you don’t want to walk the jetty’s full length — especially if you’re fully dressed in wetsuit, BC and tank — there’s a cute little petrol engine train that cruises down the deck at 5 miles per hour. The jetty is also Australia’s largest artificial reef, with a surprising diversity of marine life for a structure located at 33 degrees south of the equator (latitude). The Leeuwin Current brings a narrow band of warm water down the coast of Western Australia each winter, allowing tropical and subtropical species of animals and corals to thrive on, under and around this particular jetty.

Busselton Jetty’s hundreds of wooden pylons are covered in a vibrant tapestry of corals, sponges and other benthic invertebrates. Colorful cowry shells and nudibranchs, such as the short-tailed ceratosoma, can be found among the vertical growth, while schools of shimmering old wives, amberjacks and buffalo bream weave in and out of the cover of the jetty.

In the nearby sea-grass beds, Australian giant cuttlefish, squid and swimmer crabs hunt for tiny crustaceans. Western blue groupers — actually a type of wrasse — are among the jetty’s most inquisitive fish, coming right up to divers for a closer look at the strange bubble-blowers.

But one of the best aspects of the jetty is that even nondivers can enjoy its rich underwater ecosystem — an underwater observatory at the end of the jetty allows anyone to view and appreciate the marine life through 11 viewing windows at various levels within the observation chamber.

The jetty has been closed to divers for the past year for a massive $23.7 million restoration project and is scheduled to reopen to divers in October. The facelift includes new sections and widened decks, adding even more wooden and steel pylons for marine life to colonize in the years to come.

Make It Happen

Fly to Perth, Western Australia, then drive south three hours to Busselton. Conditions are best during the summer months (November through February), particularly in December, with visibility up to 100 feet. The Dive Shed in Busselton (www.diveshed.com.au) has daily trips to the jetty for around $80 including all gear. Cape Dive Centre in Donsborough (www.capedive.com) also has daily trips to Busselton Jetty, which is a 25- to 30-minute boat ride from Donsborough, or the wreck of the HMAS Swan, for $115 for two dives.

Alexander MustardA sea robin searches for food along the sandy bottom at the Blue Heron Bridge.

If you think you need to scour the world in search of remote pinnacles, lonely outposts and uninhabited islands to find the best diving, think again. Some of the best diving spots on the planet are literally under your feet: Piers and jetties — man-made wonders of a practical nature — have transformed into thriving marine kingdoms. From Washington state’s Keystone Jetty and Florida’s Blue Heron Bridge to the Samarai Wharf of Papua New Guinea, these are seven of the most dynamic jetty dives in the world.

Alexander MustardSeahorses mate in the twilight of Florida's setting sun.

Blue Heron Bridge, Florida

It might not be a jetty in the strictest sense (though it is used to tie up boats), but Florida’s best shore dive is one of those can’t-wait-to-get-under experiences rendered all the more surprising by its incongruous topside surrounds — a rushing overpass, South Florida’s ubiquitous looming condoscape and even a power plant off in the distance. Once you’re submerged at the Blue Heron Bridge, an intoxicating universe of critters is the only view worth considering.

The area surrounding the bridge is constantly fed and renewed by the flow of nutrients sloshing in from the Atlantic, which has brought in an explosion of life that calls this stretch of the Intracoastal Waterway between Palm Beach and Singer Island home. The Little Blue Heron Bridge, the bridge’s easternmost stretch, is under construction until late 2011, so you can’t get under it for now. But divers can still scope the south side for a chance to see striated and hairy frogfishes and longsnout seahorses that are in abundance. Another prime spot for seeing frogfish is along the mooring ball lines of sailboats that have been berthed near the small beach.

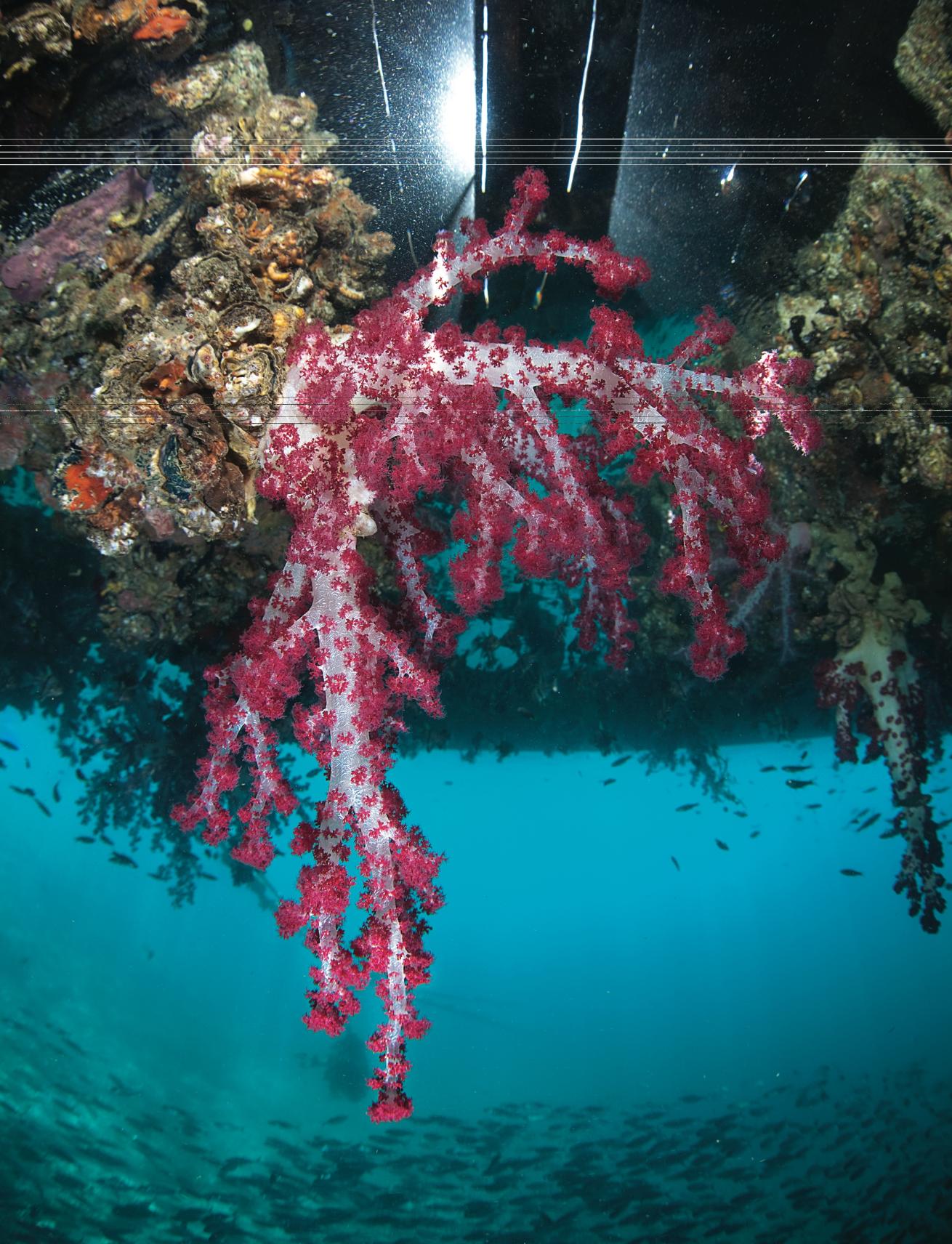

Ethan DanielsSoft corals grow to within inches of the planks.

As you float over the rubble bottom, look for sea robins and red-lipped batfish. Bristle worms, urchins and pincushion starfish abound. And it’s worth training your macro vision for surprises like bumblebee shrimp, sometimes spotted going for a starfish stroll. A rustle in the sand could be anything: a peacock flounder, perhaps, or a spooked razorfish. Octopuses are omnipresent, but you have to know where to look — they are often seen in discarded bottles that have escaped divers’ cleanup efforts.

On the main stretch of the eastern Blue Heron Bridge, wooden fenders appear to have been painted by a crayon-crazed kid with a penchant for clashing colors — orange soft corals and sponges and purple barrel sponges carpet the scene. Seaweed blennies peek curiously from their barrel burrows, while off in the deeper water, Bermuda chubs school. You’ll probably see hogfish and stoplight parrotfish here too at depths that don’t pass 16 feet (the rest of the dive barely dips below the 10-foot mark). It’s loads of bottom time for observing curious behaviors that often get lost in the larger dive fray. — Terry Ward

Ethan DanielsA cuttlefish and lionfish in a field of spiny urchins.

Make It Happen

Grab a parking spot at Phil Foster Park in Riviera Beach on the north side of the bridge, and plan your dive for the two-hour window either side of high tide. Make a day of it by heading out on a charter with Walker’s Dive Charters (www.walkersdivecharters.com), and you’ll get to dive one of the thriving nearby reefs or wrecks while waiting for the bridge’s tidal window (a two-tank dive costs $70 per person). Water temperatures range from the mid-80s in the summer months to the 70s and 60s in the winter, and visibility is usually between 50 and 80 feet (though up to 100 feet is possible).

Samarai Wharf, PNG

Colonized in the 1880s, Samarai Island was once the largest town in Papua and a magnet for “Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits.” Eventually Port Moresby became the center for government, and Samarai was virtually abandoned, leaving behind a succession of wharves built to accommodate visiting missionary boats, pearling and gold-prospecting luggers, international steamships and government launches.

The eastern section of the wharf still stands; the middle section was demolished and the west section left to fall apart. A pearl farm — gallantly breeding gold lip pearl shell in a bio-clean room inside an ancient warehouse — has brought back enterprise, and happy greetings are the rule from the friendly inhabitants. But Samarai is a shadow of its former glory.

Except underwater. Here it has never been better.

Caressed by the notorious tidal currents of the China Strait, the wharf piles are havens for a miraculous multitude of marine creatures. Yellow tubastraea corals, polyps blooming even in daytime, provide a golden-yellow backdrop to swirling baitfish, batfish, convictfish, catfish and angelfish — including the elsewhere-rare black Samarai angelfish, now named after Tawali Dive Resort operator Rob Vanderloos. A wobbegong shark is usually resting in the shade of the wharf along with scorpionfish, stonefish, toadfish, crocodilefish and octopuses.

Divers wanting a change from critter hunting can scavenge for torpedo and marble-stoppered bottles from the 1890s. Poorly blown, with imbedded bubbles, the most sought after is the marble bottle marked “Patchings — Samarai” made especially for the soda factory on the island. Current-scoured sand gutters off the wharf are good places to search for old bottles. Lively reef patches edge the gutters where resident lionfish, damsels and featherstars hide the lairs of mantis shrimp. A rusty, overgrown anchor juts out from the seabed, an unusual maroon-colored sea star snuggling a fluke.

Care needs to be taken to avoid fishing-line snares and sharp-edged clams, and a Port Moresby tide chart is useful to predict Samarai slack current — two hours before and four hours after high tide in Moresby. And you might very well use all those six hours —with a maximum depth of just 40 feet, you could be exploring the Samarai Wharf for a long time. — Bob Halstead

Michele WestmorelandDominica's Cabrits Pier is home to a number of odd critters, like this spotted moray eel and arrow crab.

Make It Happen

Samarai is one hour by speedboat from the Milne Bay provincial capital of Alotau. Diving is year-round, as the site is sheltered (as most wharves are!). Water temperatures vary from 79 degrees F in the winter (July and August) to 84 degrees F in the summer. Visibility ranges from 30 to 60 feet. Live-aboards MV Golden Dawn, FeBrina, Chertan and Spirit of Niugini occasionally include Samarai on their itineraries. Tawali Dive Resort (www.tawali.com) offers day trips to Samarai for its guests. A six-night, 15-dive package at Tawali starts at $1,912 per person. Per night rates for the live-aboards run from $285 (Chertan), $340 to $360 (Spirit of Niugini), $395 (FeBrina) and $350 to $400 (Golden Dawn). Small speedboats use the wharf area, so take caution if surfacing away from dive boat. The dive flag is not recognized by villagers, so it’s best to surface right at the dive boat or tender.

Steve SimonsenFrench angelfish and snapper swarm the shallows of St. Croix's Frederiksted Pier.

Cendana Pearl Farm Pier, Raja Ampat, Indonesia

Dropping down into the shady parts under Alyui Bay’s Cendana Pearl Farm Pier in Raja Ampat, it’s apparent that marine life is at its most robust here. Sunlight sparkles along the edges of the main platform and peeks through the wooden slats to create striking light beams, but most fish and invertebrates prefer the dim confines beneath the pier.

Ignoring divers, well-fed stonefish show their grumpy-looking countenances next to matching mounds of living rock. With incessant currents carrying plankton to the waiting mouths of filter feeders, the stonefish barely have to move in order to feed on large numbers of unsuspecting cardinalfish, damsels or gobies. Not far away, a pair of banded pipefish poke their slender snouts out from crevices, a juvenile crocodilefish mimics a drowned tree branch and a juvenile cuttlefish camouflages itself amid crinoids and sponges. Tear your gaze away from the life on the critter-laden bottom and look upward, where you’ll see a massive school of scad form a silver river of fish slipping between the pier pilings. Onlookers from above, longfin spadefish hover over the scad, watching the parade.

Located near the mouth of the Alyui Bay on the western edge of Waigeo Island, the pearl farm is swept by healthy, nutrient-rich waters that allow prolific marine growth, especially under its main pier. The bay is a large maze of forested islands, limestone islets, thick mangroves and narrow channels that serve as nurseries, reproductive sites and feeding grounds for thousands of marine species. A number of excellent dive sites for both critters and wide-angle scenery are found throughout the area, minutes from any anchorage. Though several nearby channels can provide exhilarating drifts, the Cendana Pier consistently offers light currents and profuse life that is difficult to match.

Every other dive under the pier turns up a resident tasseled wobbegong, which evidently appreciates the abundance of food associated with the pier. Another shark often found amid the mushroom leather corals growing along the pier is the Raja epaulette shark, one of the region’s unusual endemics. The pier, its pilings and surrounding habitat are absolutely loaded with the bizarre creatures that divers have a special affinity for, from tiny shrimp, frogfish and waspfish to sweeping scenes of reef diversity. Dappled by light and shadows, sponges, soft corals, gorgonians, bivalves and delicate tunicates clutter the site with dreamlike scenery, which is as good as it gets no matter what divers are in search of. — Ethan Daniels

Tanya Burnett-PalmerDivers prepare for a morning under the pier.

Make It Happen

With a number of interesting dive sites, Alyui Bay is a common stop for live-aboards exploring Raja Ampat’s northern islands. Though the pier is used on a daily basis for loading and unloading pearl-farm equipment, it can be dived at almost any time of day or night with permission from the farm management. Water temperatures are fairly constant, ranging between 81 to 84 degrees F year-round, but visibility can vary from 40 to 70 feet depending on the tide and weather. Live-aboards can anchor within minutes of the pier and, due to it being fairly shallow (between 3 and 45 feet), divers can expect to stay under the dock for long periods. Eleven-night trips on board the Paradise Dancer start from $4,750.

Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier, Dominica

The payoff in diving Dominica’s Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier comes almost immediately. Shortnose batfish favor the sand-rubble bottom, and divemasters routinely point out these 5-inch walking oddities with noses that rival Cyrano de Bergerac’s. With pectoral and pelvic fins that resemble hands and feet, batfish actually “walk,” and will move clumsily away from divers, fluttering slightly above the bottom as they try to find a new place to hide under the pier.

The wooden pier — named Pole to Pole by local operators — is located on the island’s northwestern coast in Prince Rupert Bay. The bay is sheltered on its northern side by the Cabrits headland, a rugged, volcanic outcropping that juts from the mainland. There are terrific sites north of the Cabrits peninsula, but unpredictable strong currents and swells from the north can sometimes cancel the diving at less-protected places. In contrast, the pier offers calm conditions and reliable visibility in just 48 feet of water, day or night.

The pier’s legs are plastered with sponges — a profusion of finger, encrusting and tube sponges vie for real estate — and longsnout seahorses are tucked in between the mass of life. Batfish and seahorses aren’t the only creatures making a living under the pier. Comical-looking balloonfish hide in crevices. Jawfish poke their heads out from the safety of hiding places among the piles of small boulders and debris. Get even closer to spot yellowline arrow crabs gingerly high-stepping out of cracks, shy secretary blennies peeking from their tiny burrows and spotted cleaner and coral banded shrimp clinging to bottles that have become part of the underwater landscape. This is a place of refuge for peacock flounders, frogfish and juveniles of many reef species like blue and brown chromis, sergeant majors, gobies and barred hamlets.

Divers can spend all their bottom time finning from one pole to the next, but there’s also plenty to explore adjacent to the pier: Creatures like urchins and lobsters hide in the rocky boulders jumbled atop one another, and sand eels and flying gurnards are found in the sand flats. Muck diving can sound unappealing — the best muck sites are in shallow water with a fair bit of debris like discarded tires, engine parts and bottles strewn about — but savvy divers know these sites deliver a rich habitat populated by bizarre and colorful creatures. More commonly associated with Pacific destinations like Indonesia’s Lembeh Strait and Papua New Guinea’s Milne Bay, outstanding muck experiences can also be found in the Caribbean, often underneath piers like Pole to Pole. All divers need is a camera equipped with a macro lens — and an appreciation for the weird and wonderful. — Patricia Wuest

Make It Happen

The Cabrits Cruise Ship Pier is only occasionally used as a berth by cruise ships (most dock in Roseau on the southwestern end of the island). Pole to Pole can be dived from either shore or boat, day or night. Water temperatures range from 78 degrees F in winter to 83 degrees F in summer, and visibility is a dependable 50 to 60 feet, though it can be as good as 100 feet. Cabrits Dive Centre (www.cabritsdive.com) in Portsmouth puts divers in the water at the pier in less than 10 minutes from where its boat is docked. Two-tank guided boat dives start from $87.50 and one-tank night dives from $65.50. One of the owners is British, so tea and biscuits are often served on board. Brilliant.

Keystone Jetty, Washington

Part of Fort Casey State Park, Keystone Jetty operates as a ferry landing for bucolic Whidby Island in the Puget Sound. It’s a quick escape for the hard-core dive community in Seattle, and one of the top dives in the area, renowned for its biodiversity. It’s strictly shore diving and the deepest part of the dive is only about 55 feet, with some of the best stuff in the shallower parts.

There are actually two places to dive in this protected marine area: the old pier and the breakwall that protects the ferry landing. There are picnic tables, toilets and even a hot-water shower to help thaw you out after a dive in the average 50 degree F water.

But the encounters make it worth the effort to dive the jetty. Massive lingcod with heads the size of soccer balls sit and stare you down. Giant Pacific octopuses also call the jetty home and are found along the breakwall, and if you’re lucky, one of these playful critters will interact with you. Consider yourself warned, though: There are tales of these giant octopuses removing divers’ masks in a moment of curiosity, so stay alert around them.

The pilings of the pier are covered in anemones and, like most piers, harbor legions of macro critters including a variety of nudibranchs and invertebrates. Bull kelp adds a surreal aspect to the dive, punctuated by snow-white plumrose anemones. Perch, cabezon and giant barnacles also like the pier, and the omnipresent barnacles are a sign of one certainty about diving here in Puget Sound: current. It’s best to plan to dive at slack tide and explore slowly. Cold-water marine life tends to prefer stillness, so you could easily miss something if you’re off to the races. If you have a chance, dive the Keystone Jetty midweek, when you’ll have the site all to yourself. — Ty Sawyer

Make It Happen

Whidby is about 30 miles north of Seattle. You can drive in via the north side of the island, which takes you over Deception Pass and its scenic bridge, or take the Mukilteo Ferry, which leaves from the town of Everett. From the Whidby landing, it’s about a 26-mile drive. From Port Townsend, you can take the ferry directly to Keystone.

Frederiksted Pier, St. Croix

St. Croix’s Frederiksted Pier is a tale of two dives. The original pier was virtually destroyed by Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Most of the parts left standing were towed to another dive site, and a new Frederiksted Pier was built in its place. In just a few years, marine life has already taken hold, and together, the two piers have become one of the Caribbean’s hottest dive sites.

As you head out to the new pier, you’ll pass some pilings and “dolphins” from the old pier, as well as some scattered debris courtesy of Hugo. Don’t rush through the old section, though, as it’s a perfect hiding spot for seahorses, trunkfish, batfish and lots of moray eels.

It takes many divers many dives to get past the section that’s left from the original pier. But ignore the new pier at your peril — it ripples with the syncopated streams of baitfish that wind and spin around the pilings in the shallow water. Sponges are becoming increasingly prominent, and frogfish, batfish and seahorses have taken up residence along the new pier’s pylons.

If you have the time, make both a day dive and a night dive. Like all great pier dives, the Frederiksted Pier erupts at night. Several species of shrimp reveal themselves with shining eyes, and octopuses come out to patrol through the remains. The new pier also plays host to a number of topside activities, so check with the shops to see what might be going on during your night dive. For example, bands often play on the pier at night, so your dive might be accompanied by the not-so-distant sounds of steel drums. — Ty Sawyer

Make It Happen

The Frederiksted Pier is as famous as the beer-swilling pig at the Montpellier Domino Club. Every dive shop on the island will visit the site at least once during a typical week of diving; if you want to dive it more than once, arrange to do a shore dive.

Busselton Jetty, Western Australia

In a country with no shortage of outstanding jetty dives (including Exmouth Navy Pier, Rapid Bay Jetty and Edithburgh Jetty), Western Australia’s Busselton Jetty outshines them all. Standing on Busselton’s white-sand beach, the jetty seems to extend all the way to the horizon, where a cloudless Western Australian sky meets an equally blue Indian Ocean. In fact, at 6,040 feet long, picturesque Busselton Jetty is the longest wooden jetty in the southern hemisphere.

But it didn’t start out that way. Built in 1865 to service whaling and other types of vessels, the jetty’s original length was 518 feet. Seven extensions were added by the turn of the 20th century thanks to Western Australia’s booming resource trade.

Nowadays the jetty is a tourist attraction, drawing more than 400,000 visitors each year. And if you don’t want to walk the jetty’s full length — especially if you’re fully dressed in wetsuit, BC and tank — there’s a cute little petrol engine train that cruises down the deck at 5 miles per hour. The jetty is also Australia’s largest artificial reef, with a surprising diversity of marine life for a structure located at 33 degrees south of the equator (latitude). The Leeuwin Current brings a narrow band of warm water down the coast of Western Australia each winter, allowing tropical and subtropical species of animals and corals to thrive on, under and around this particular jetty.

Busselton Jetty’s hundreds of wooden pylons are covered in a vibrant tapestry of corals, sponges and other benthic invertebrates. Colorful cowry shells and nudibranchs, such as the short-tailed ceratosoma, can be found among the vertical growth, while schools of shimmering old wives, amberjacks and buffalo bream weave in and out of the cover of the jetty.

In the nearby sea-grass beds, Australian giant cuttlefish, squid and swimmer crabs hunt for tiny crustaceans. Western blue groupers — actually a type of wrasse — are among the jetty’s most inquisitive fish, coming right up to divers for a closer look at the strange bubble-blowers.

But one of the best aspects of the jetty is that even nondivers can enjoy its rich underwater ecosystem — an underwater observatory at the end of the jetty allows anyone to view and appreciate the marine life through 11 viewing windows at various levels within the observation chamber.

The jetty has been closed to divers for the past year for a massive $23.7 million restoration project and is scheduled to reopen to divers in October. The facelift includes new sections and widened decks, adding even more wooden and steel pylons for marine life to colonize in the years to come.

Make It Happen

Fly to Perth, Western Australia, then drive south three hours to Busselton. Conditions are best during the summer months (November through February), particularly in December, with visibility up to 100 feet. The Dive Shed in Busselton (www.diveshed.com.au) has daily trips to the jetty for around $80 including all gear. Cape Dive Centre in Donsborough (www.capedive.com) also has daily trips to Busselton Jetty, which is a 25- to 30-minute boat ride from Donsborough, or the wreck of the HMAS Swan, for $115 for two dives.