Understanding the Secret Lives of Whale Sharks

iStockA long-term study in Western Australia gained insight into the movement patterns of the whale shark. Migration patterns of marine species like whale sharks are often poorly understood due to the logistical challenges of surveying these highly mobile and often elusive animals, according to researchers.

People flock from all over the world to snorkel with whale sharks, in places as diverse as Isla Contoy, Mexico, Cenderwasih Bay, Indonesia, and Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. In order to help with conservation efforts to help protect whale sharks, researchers from the University of Queensland and the Western Australia-based nonprofit ECOCEAN undertook a 5-year-long study to track and record the migration of whale sharks to and from Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia.

UQ graduate and ECOCEAN marine biologist Samantha Reynolds said the study gave researchers insights into the importance of the Ningaloo Reef area to whale sharks.

“Our tagged whale sharks were tracked returning to Ningaloo Reef throughout the year, and our modeling suggests that it provides suitable habitat for them year-round,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds said the information was important to Western Australia’s eco-tourism industry, but she added, “It’s also vital information for the long-term management and conservation of whale sharks. They are an endangered species. We need to know which areas are critical habitat for them, so we can protect them into the future.”

Reynolds said the study is the result of an extensive satellite tracking study — conducted between 2010 and 2015 — of whale sharks in Australia.

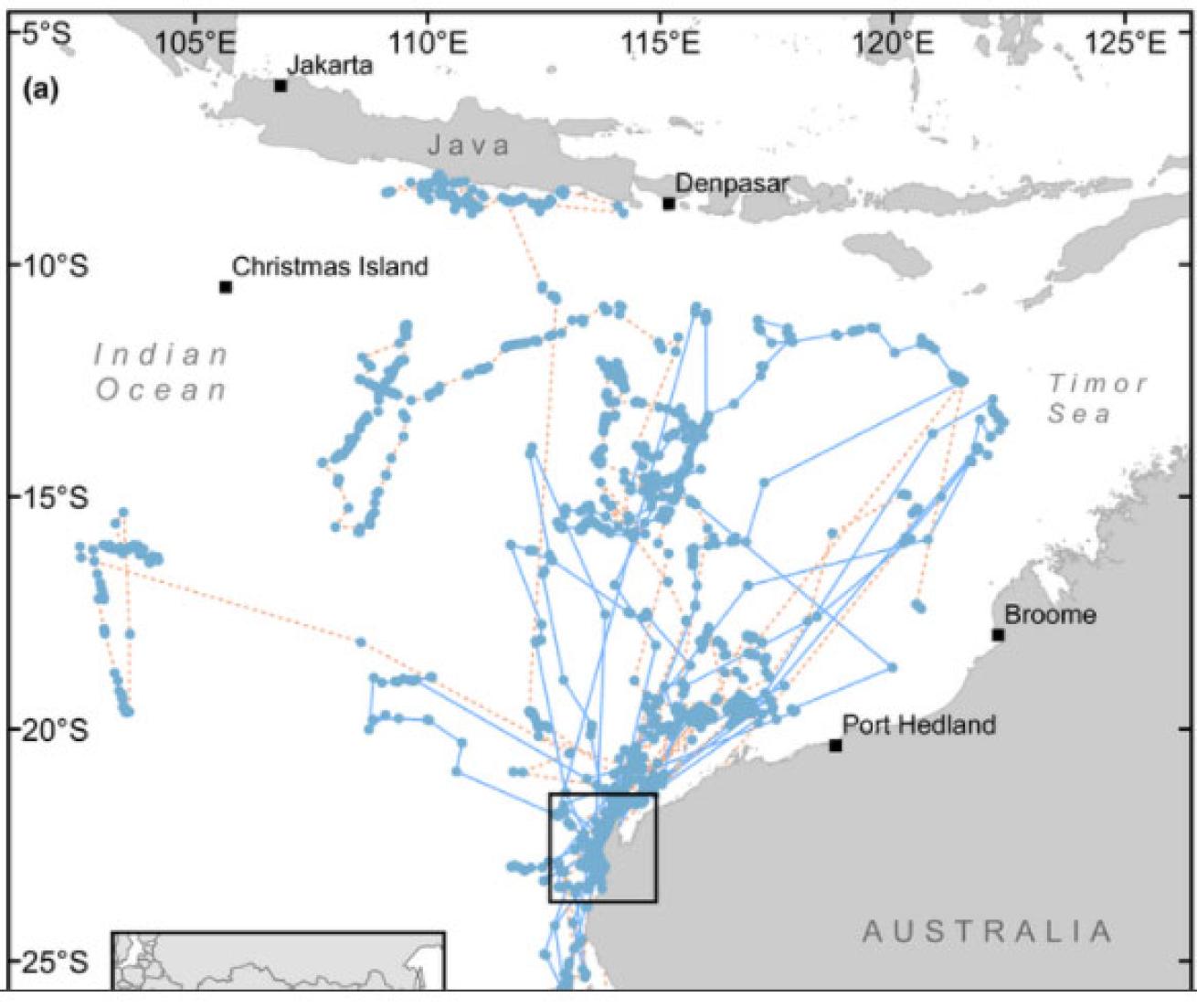

Courtesy University of QueenslandThe movement patterns of 25 whale sharks tagged with satellite-linked transmitters at Ningaloo Reef from 2010 to 2015. The blue points represent the locations where the whale sharks "pinged"; the lines show the shortest route between these pings. The blue lines also highlight those sharks — nine — that returned to Ningaloo Reef after moving at least 300 km (185 miles) away from where they were tagged, and dashed orange lines represent sharks that did not return.

The study identified areas along the Western Australia coast, in the Timor Sea, in Indonesian and in international waters that could be important whale shark habitat.

According to the IUCN — International Union for Conservation of Nature — 75 percent of the global whale shark population occurs in the Indo-Pacific, and 25 percent in the Atlantic. In the Indo-Pacific, a population reduction of 63 percent is inferred over the last three generations (75 years), and in the Atlantic, a population reduction of more than 30 percent is inferred. Combining data from both regions, it is likely that the global whale shark population has declined by more than 50 percent over the last 75 years.

“Our study highlights the need for international cooperation for the protection of whale sharks,” Reynolds said. “Many of these areas are not designated as Marine Protected Areas and some of the tagged sharks we studied traveled to areas where they could be under threat from ship strike, pollution or targeted fishing. The conservation status of whale sharks was changed from vulnerable to endangered last year, because of these threats.”

iStockSatellite telemetry was used to remotely track the long-term movements of more than two dozen whale sharks.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are slow-moving filter-feeding carpet sharks, which live an average of 80 years or so, with the largest confirmed individual weighing about 21.5 tons with a length of 12.65 meters or 41 feet.

FOR MORE: 7 Facts about Whale Sharks

The research, published in Diversity and Distributions, is ongoing, with additional satellite tagging.