Saving Cuba's Gardens of the Queen

A frustrated Anderson Cooper is trying to complete a stand-up — newscaster parlance for delivering lines while standing near your subject, looking directly into the camera. But Cooper is nearly 90 feet below the surface of the Caribbean Sea, roughly 50 miles off Cuba’s southern coast within the Gardens of the Queen marine park, one the largest protected areas in the Caribbean. A dizzying procession of Caribbean reef sharks, oversized Goliath grouper and black grouper constantly swims between Cooper and camera, blocking the shot. Only after countless takes and a nearly empty cylinder was the 60 Minutes correspondent willing to leave his post.

The irony was striking. In too many corners of the Caribbean, we feel fortunate to encounter one such sizeable fish during a dive. Populations of large predatory fish have declined by nearly 90 percent worldwide over the past 50 years, victims of overfishing and the demise of coral habitats that support them.

In contrast, Gardens of the Queen — Jardines de la Reina, named by Christopher Columbus to honor Queen Isabel of Spain — remains as spectacularly beautiful and wild as when Columbus experienced it more than 500 years ago, teeming with healthy corals, bonefish, cubera snapper, sharks, whale sharks, orcas and even sperm whales.

The extraordinary health of the Gardens is disarming. During my 40 years as a scuba diver, I have had a front-row seat to a disaster in slow motion as coral reefs nearly everywhere have become diseased, bleached, eroded, crushed and swept away by the tide. The coral reefs of the Florida Keys where I spent the summers of my teen years are nearly unrecognizable compared to what I first experienced in 1974. Climate change, ocean acidification, overfishing, nutrient pollution and other impacts are taking an alarming toll. In recent years I had found it harder and harder to stay positive in my writing, advocacy and public lectures.

Then, just as I was about to lose all hope, Cuba came to my rescue.

During expeditions along Cuba's northwestern coast, I was greeted by vast, robust stands of healthy, colorful corals that hadn’t received the memo about their demise. And then it got better — much better.

When I first set eyes on the Gardens of the Queen, I suddenly felt like my teenage self again, greeting old friends like Nassau grouper (now critically endangered), stand upon stand of healthy elkhorn coral (now estimated to be 95 percent extinct from the Caribbean), and magnificent pillar corals.

So why is this place so healthy? That’s the basis of our collaborative work with Cuban scientists. The Gardens of the Queen represent a unique opportunity to understand how a pristine coral reef ecosystem works, gain insight as to why it's so healthy, and guide our conservation efforts for coral reef ecosystems around the Caribbean and the world.

Part of the answer lies in the fact that Cubans are strongly committed to protecting this treasure, now in its 17th year as a no-take marine park. There is virtually no infrastructure here — just a small floating hotel and modest fleet of live-aboards managed by Avalon Cuban Diving Centers (cubandivingcenters.com), which has an agreement with the Cuban government to run the only diving and fishing operation in the Gargens. Only 1,000 divers and 500 fishermen are allowed to visit the park per year. Some sites around the Caribbean see that many visitors in a day.

The Gardens’ success goes beyond a healthy ecosystem. In a country that has faced grave economic challenges, Cuba’s burgeoning ecotourism industry is making a profound difference in the lives of Cuban citizens. Many who used to fish in the Gardens are now employees at the park, earning far more keeping those same fish alive.

Cuba and the United States are often described as separated by the Straits of Florida. But to a marine scientist, nothing could be further from the truth. These waters tightly connect Cuba and the U.S. through a network of strong ocean currents and myriad marine life that lives within them, from the tiniest plankton to the largest whales. Studies show that Cuban fish grow up to be American fish. The two countries share a rich and dynamic marine ecosystem that is impossible to fully study, understand or protect without strong international collaboration. My experience has been that some of the best diplomacy happens with a tank on your back.

If you are fortunate enough to visit Cuba, prepare for an unforgettable journey through time and a joyful reunion with some very special friends, including the warm, welcoming people of Cuba and once-familiar undersea creatures that have found refuge in this island's unspoiled waters.

Along the way, you may just run into another old friend: the fervent optimism of your youth.

Get Involved

Learn more about Ocean Doctor's Cuba Conservancy Program at OceanDoctor.org/Cuba

Support Ocean Doctor's work in Cuba's Gardens of the Queen with a tax-deductible donation at OceanDoctor.org/Donate

Participate in Ocean Doctor’s Cuba Travel Program and join Cuban science teams in Cuba for an unforgettable visit to Cuba's Gardens of the Queen: OceanDoctor.org/Gardens

Watch the 60 Minutes segment, The Gardens of the Queen, at OceanDoctor.org/60minutes

Courtesy Noel Lopez/Avalon Cuban Diving CentersCrocs are among the diverse marine life that have found a home in Cuba's Gardens of the Queen.

A frustrated Anderson Cooper is trying to complete a stand-up — newscaster parlance for delivering lines while standing near your subject, looking directly into the camera. But Cooper is nearly 90 feet below the surface of the Caribbean Sea, roughly 50 miles off Cuba’s southern coast within the Gardens of the Queen marine park, one the largest protected areas in the Caribbean. A dizzying procession of Caribbean reef sharks, oversized Goliath grouper and black grouper constantly swims between Cooper and camera, blocking the shot. Only after countless takes and a nearly empty cylinder was the 60 Minutes correspondent willing to leave his post.

The irony was striking. In too many corners of the Caribbean, we feel fortunate to encounter one such sizeable fish during a dive. Populations of large predatory fish have declined by nearly 90 percent worldwide over the past 50 years, victims of overfishing and the demise of coral habitats that support them.

Courtesy Fausto de Nevi Herrera/Avalon Cuban Diving CentersLos Jardines de la Reina, or the Gardens of the Queen, harbors a thriving shark population, including silky sharks, Caribbean reef sharks and whale sharks.

In contrast, Gardens of the Queen — Jardines de la Reina, named by Christopher Columbus to honor Queen Isabel of Spain — remains as spectacularly beautiful and wild as when Columbus experienced it more than 500 years ago, teeming with healthy corals, bonefish, cubera snapper, sharks, whale sharks, orcas and even sperm whales.

The extraordinary health of the Gardens is disarming. During my 40 years as a scuba diver, I have had a front-row seat to a disaster in slow motion as coral reefs nearly everywhere have become diseased, bleached, eroded, crushed and swept away by the tide. The coral reefs of the Florida Keys where I spent the summers of my teen years are nearly unrecognizable compared to what I first experienced in 1974. Climate change, ocean acidification, overfishing, nutrient pollution and other impacts are taking an alarming toll. In recent years I had found it harder and harder to stay positive in my writing, advocacy and public lectures.

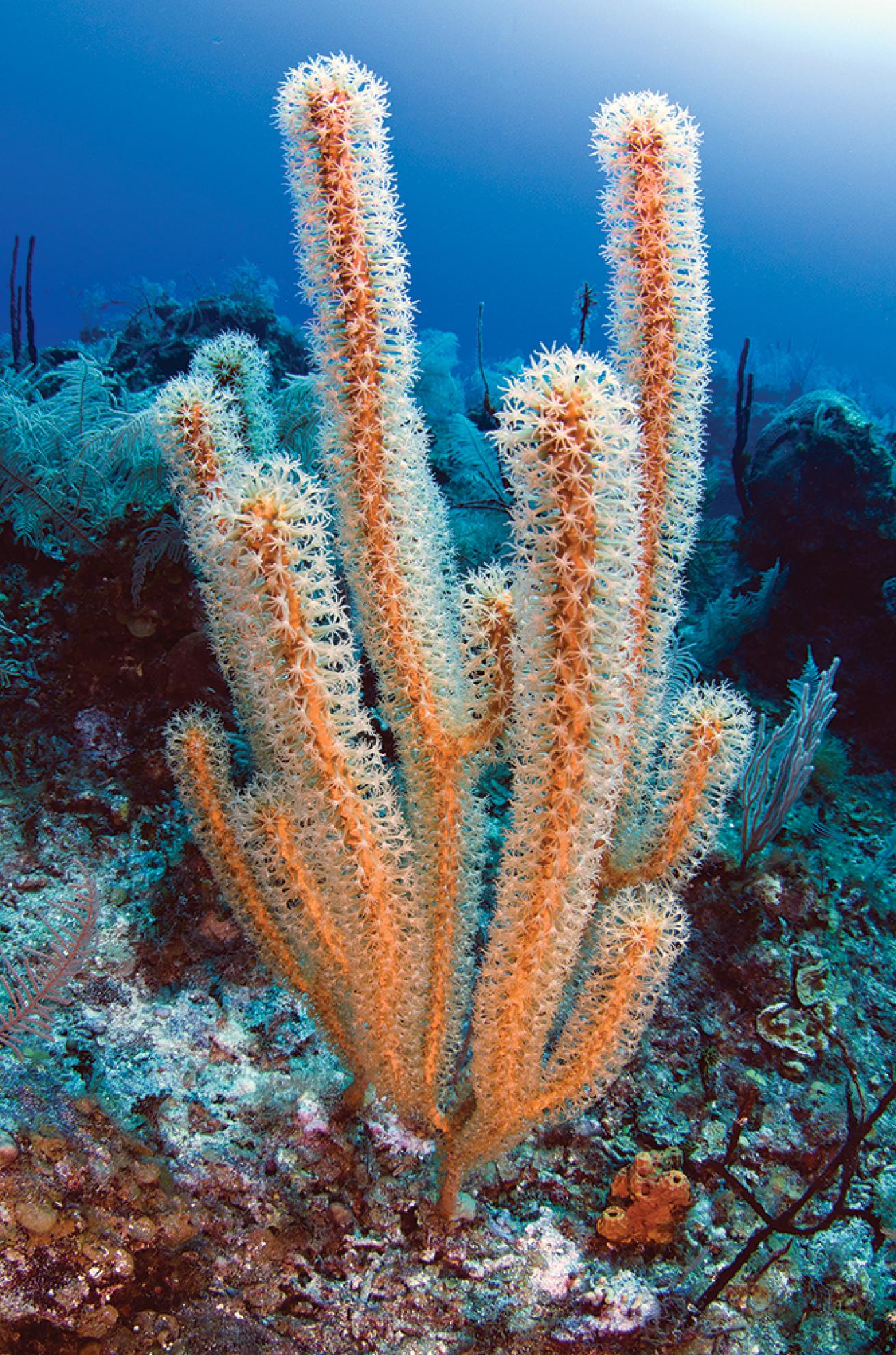

Pete Oxford/Minden Pictures/CorbisCuba's Gardens of the Queen National Park is abundant with remarkably healthy coral and fish populations.

Then, just as I was about to lose all hope, Cuba came to my rescue.

During expeditions along Cuba's northwestern coast, I was greeted by vast, robust stands of healthy, colorful corals that hadn’t received the memo about their demise. And then it got better — much better.

When I first set eyes on the Gardens of the Queen, I suddenly felt like my teenage self again, greeting old friends like Nassau grouper (now critically endangered), stand upon stand of healthy elkhorn coral (now estimated to be 95 percent extinct from the Caribbean), and magnificent pillar corals.

So why is this place so healthy? That’s the basis of our collaborative work with Cuban scientists. The Gardens of the Queen represent a unique opportunity to understand how a pristine coral reef ecosystem works, gain insight as to why it's so healthy, and guide our conservation efforts for coral reef ecosystems around the Caribbean and the world.

Courtesy CBS News/60 MinutesCorrespondent Anderson Cooper tries to get a word in for a 60 Minutes piece on Cuba's Gardens of the Queen.

Part of the answer lies in the fact that Cubans are strongly committed to protecting this treasure, now in its 17th year as a no-take marine park. There is virtually no infrastructure here — just a small floating hotel and modest fleet of live-aboards managed by Avalon Cuban Diving Centers (cubandivingcenters.com), which has an agreement with the Cuban government to run the only diving and fishing operation in the Gargens. Only 1,000 divers and 500 fishermen are allowed to visit the park per year. Some sites around the Caribbean see that many visitors in a day.

The Gardens’ success goes beyond a healthy ecosystem. In a country that has faced grave economic challenges, Cuba’s burgeoning ecotourism industry is making a profound difference in the lives of Cuban citizens. Many who used to fish in the Gardens are now employees at the park, earning far more keeping those same fish alive.

Cuba and the United States are often described as separated by the Straits of Florida. But to a marine scientist, nothing could be further from the truth. These waters tightly connect Cuba and the U.S. through a network of strong ocean currents and myriad marine life that lives within them, from the tiniest plankton to the largest whales. Studies show that Cuban fish grow up to be American fish. The two countries share a rich and dynamic marine ecosystem that is impossible to fully study, understand or protect without strong international collaboration. My experience has been that some of the best diplomacy happens with a tank on your back.

If you are fortunate enough to visit Cuba, prepare for an unforgettable journey through time and a joyful reunion with some very special friends, including the warm, welcoming people of Cuba and once-familiar undersea creatures that have found refuge in this island's unspoiled waters.

Along the way, you may just run into another old friend: the fervent optimism of your youth.

Get Involved

Learn more about Ocean Doctor's Cuba Conservancy Program at OceanDoctor.org/Cuba

Support Ocean Doctor's work in Cuba's Gardens of the Queen with a tax-deductible donation at OceanDoctor.org/Donate

Participate in Ocean Doctor’s Cuba Travel Program and join Cuban science teams in Cuba for an unforgettable visit to Cuba's Gardens of the Queen: OceanDoctor.org/Gardens

Watch the 60 Minutes segment, The Gardens of the Queen, at OceanDoctor.org/60minutes