Step Inside The World’s First Sunflower Sea Star Nursery

Dennis Wise/University of WashingtonAdult sunflower sea stars feed on mussels.

As purple sea stars begin to bounce back from a wasting disease first observed in 2013, their cousins (Pycnopodia helianthoides) continue to struggle. Researchers estimate nearly 6 billion of these voracious predators have died off, making the critically endangered species functionally extinct on the West Coast south of Washington (their habitat once stretched from Alaska to Baja California). But a lab in Washington’s San Juan Islands has created the first breeding program and hopes to both understand the syndrome better and eventually reintroduce these colorful, serving-platter-size beauties.

“Marine epidemics are out of sight, out of mind. We don’t catch them often until much of the damage has already been done,” says Seattle diver and conservationist Laura James, the Emmy-winning cinematographer behind some of the earliest sea star wasting footage. “The loss of the stars was a devastating blow to ocean outreach. For as long as I can remember, the sea stars have always been our first ambassadors to the underwater world in tide pools and touch tanks at aquariums. Without them, I fear our ability to connect to the oceans at a very basic level is impaired.”

Marine biologist Jason Hodin agrees it’s easy—but perilous—to overlook the stars’ plight. He’s the senior research scientist overseeing the sunflower-larvae nursery at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, a campus sprawling over an ocean bluff fringed by firs and cedars.

“The wasting hit every single type of sea star in our region. That would be the equivalent to a disease like COVID impacting every single type of mammal, from lions to our pets, whales, bears, deer, everything,” he says. “It’s pretty dramatic and should be cause for really, really large concern.”

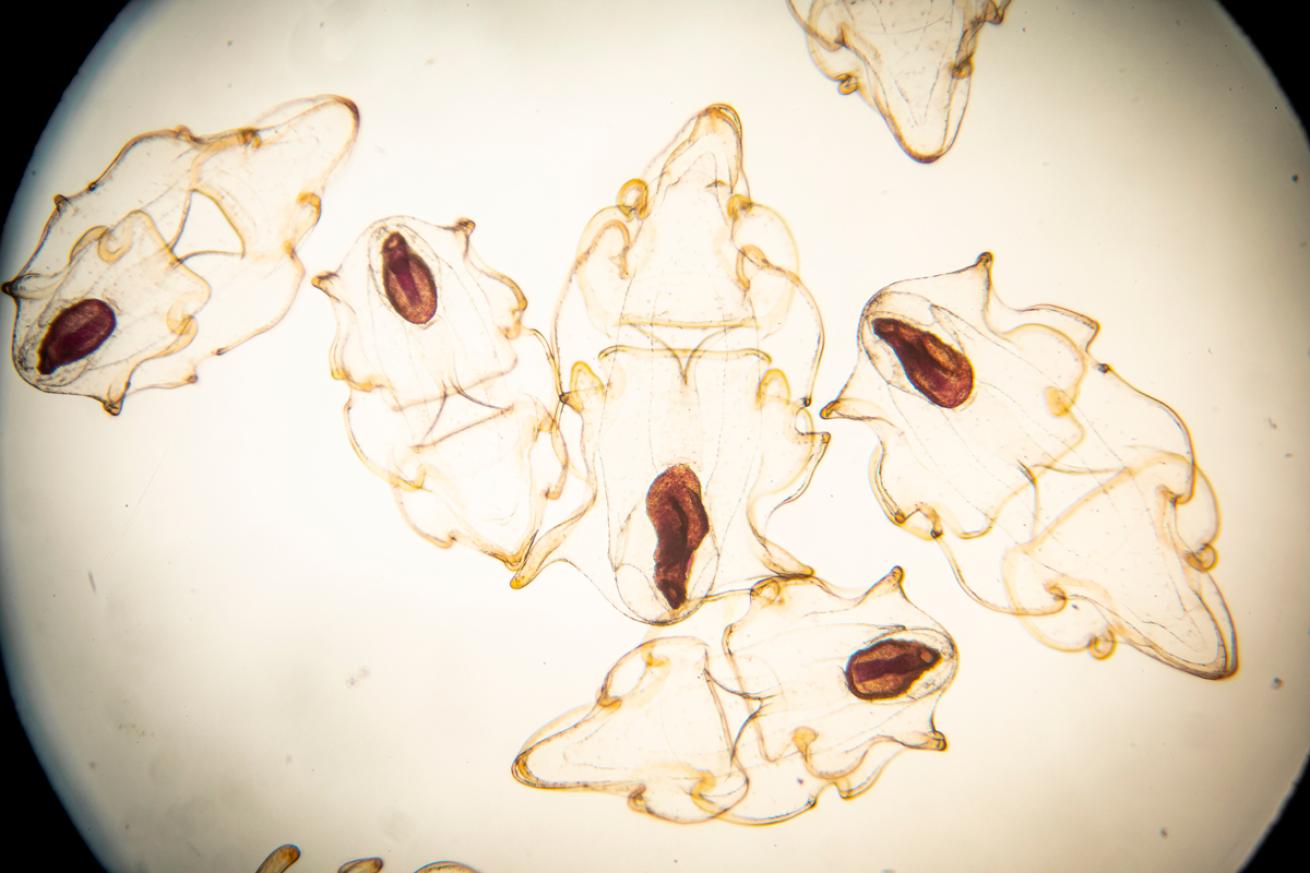

Dennis Wise/University of WashingtonLarvae under a microscope in the lab.

Scholars remain divided about the cause of the die-offs. Many suspect it could be a result of warming waters; others argue the higher temperatures are just activating an infection. And the loss of these relatively swift-moving keystone predators that can live up to 65 years is helping to unbalance ecosystems. Their primary prey, Pacific purple sea urchins, have gone largely unchecked since 2014, for example. When the supply of drift kelp dwindled, they began devouring live seaweed instead. Combined with other environmental pressures, the once-lush forests of tall, golden bull kelp have been reduced by 95 percent in Northern California, according to a study from University of California, Santa Cruz.

Dennis Wise/University of WashingtonResearchers on Jason Hodin’s team monitor sunflower sea stars at different life stages.

Hodin and his team hope to turn this bad news around, first by understanding more about the life cycle of sunflower stars, a species that has preserved its aura of mystery into the modern era. To be fair, the juveniles are smaller than a grain of rice, making oceanic observation almost impossible. But from these tiny larvae grow the world’s biggest, heaviest and fastest stars, which can reach up to 3.3 feet across and 13.4 pounds. Each star possesses 15,000 tube feet, which can barrel them along at a pace of 9.8 feet per minute.

Dennis Wise/University of WashingtonSunflower sea star larvae.

Initially, the lab didn’t even know what young sea stars ate, but the scientists soon discovered they devour juvenile purple sea urchins—five times more than adults consume, in fact!

Ethan Daniels/Shutterstock.comA full-grown adult in open water.

The team hopes to prove sunflower sea stars can be raised in captivity and to suss out whether they can be successfully transferred to open water. Someday—if the experiments go well and the nursery’s techniques can be scaled into massive aquaculture facilities—the dream would be to reintroduce these keystone predators into ecosystems like California’s coastline.

In the meantime, divers, swimmers and beachcombers can help conservation efforts by reporting sunflower star sightings online to the University of California, Santa Cruz (see “What You Can Do.”) And everyone can welcome the lab’s little bundles of joy by donating directly to the Friday Harbor Laboratories’ campaign.

What You Can Do

Report sunflower star sightings at seastarwasting.org; donate to the nursery’s efforts and learn more at tinyurl.com/starsforthesea.