Diving Newfoundland’s Frigid Underworld

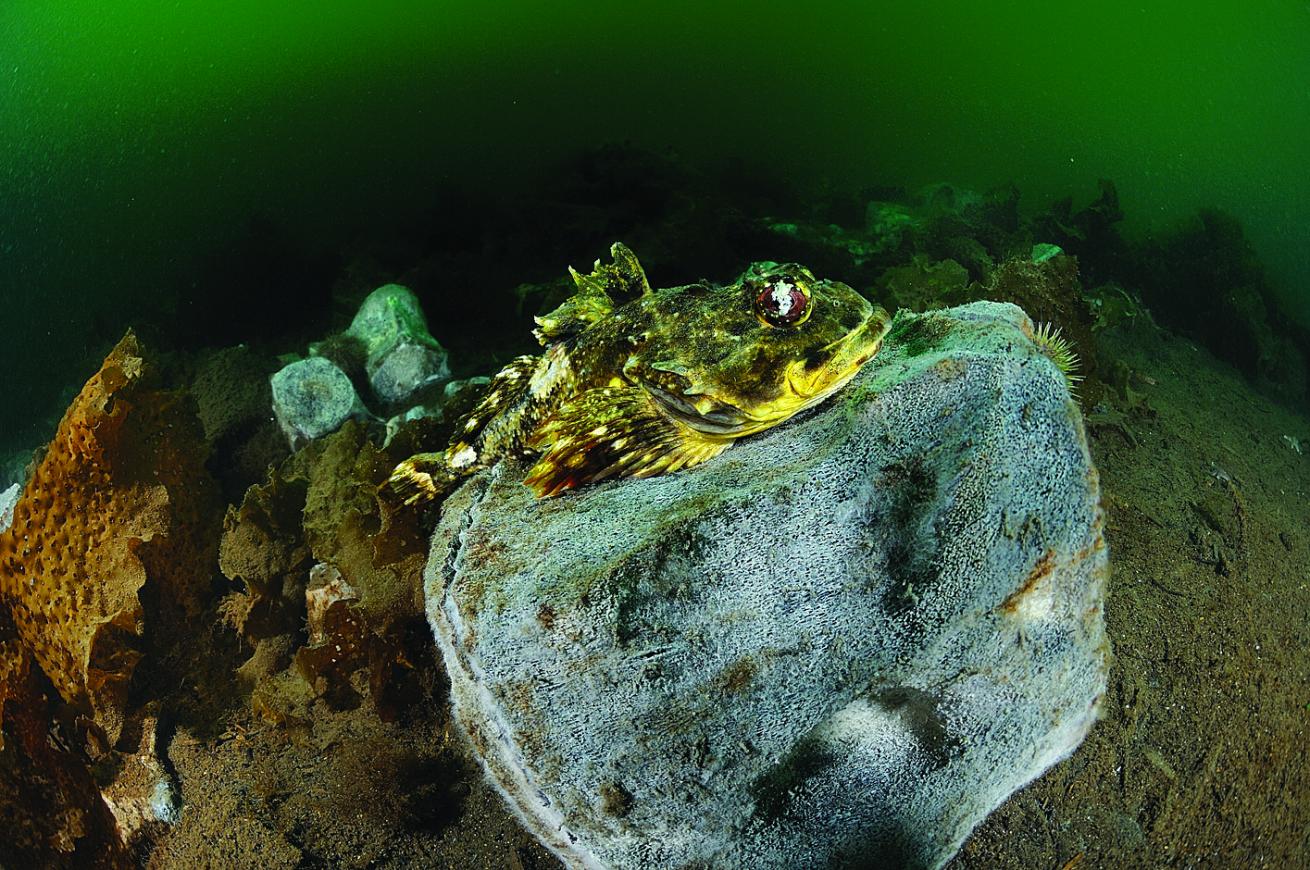

Rene LipmannThe author and photographer get their first look at Scarface, nicknamed for a massive scar on its lower jaw.

Not until Rick Stanley switches off his engines does the true spirit of this place take hold of us. Dimmed by thick clouds of mist, the grey water looks lifeless. Only the brightly coloured beaks of puffins show up against the dark cliffs that surround this sheltered bay. You can hear the wind hauling across the water as the cold starts to pierce our thick wetsuits.

All of a sudden, two white fins break the surface — in this surreal environment, a truly mystical being waits just a few yards off: a humpback whale.

Rene LipmannThe propeller of the PLM-27 is one of the many dive attractions.

I hit the water immediately. My buddy is ahead of me, reaching for the white shimmer caught by his lens. But the 50-foot whale is way too big to miss. Gracefully it passes through the water, its belly turned towards us. Throat pleats pulsate in the direction of its enormous tail — its immense movements can be felt through the water. Truly a gentle giant, the whale keeps a moderate distance and soon disappears. I can feel my heart pounding and take my first deep breath since entering the water. And then, just as suddenly, it’s back.

Two hours later, the boat nears to pick us up. Judging from the massive grin on Stanley’s face, we know this was not the average encounter. “We normally spend seconds to a few minutes with the whales,” he shouts over the engines. “You guys got two hours straight!” His face gives away his own moment of disbelief.

Rene LipmannScarface hunts capellin, a small forage fish.

Back on the boat the experience settles in, and no one is unaffected. Stanley is especially pleased by the return of this particular whale — he recognizes the humpback by the massive scar on its lower jaw, which earned its nickname, Scarface.

We have been invited here by Rick and Debbie Stanley, owners of OceanQuest. Their year-round dive and snorkel facility is located on the coast of the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, Canada. Together with Labrador, the island forms Canada’s most eastern province. Here the warm, southerly Gulfstream meets the cold Labrador Current from the north, resulting in one of the world’s richest fisheries: the Grand Banks. Abundant marine life results in millions of nesting sites for birds and the migration of thousands of whales along the coast each summer, joined by the many icebergs that calve from Greenland glaciers in spring. We are here on a 10-day adventure that will take us snorkeling with whales, diving on World War II wrecks, hiking along the East Coast Trail and canoeing and fishing in the Terra Nova National park. Our first day makes it very clear that Stanley has planned some serious action for us.

Rene LipmannA whale boneyard off the former whaling town of Dildo is a sad and forlorn spot.

A day later, we dive into the past with OceanQuest skipper and regional historian Bill Flaherty. It’s early morning as we sail across “the tickle,” the local name for the passage between Bell Island and Portugal Cove-St. Phillips. This was once the center of the local iron-ore industry — the closed mines of Bell Island reach far below the seabed of Conception Bay. There lie four massive wrecks: the SS Saganaga, Lord Strathcona, PLM-27 and SS Rose Castle.

Rene LipmannWhat awaits you apres-dive in Newfoundland? Moose soup, a local delicacy.

The sun is shining and the water looks relatively calm. Even in summer, water temperatures here do not reach far above 35 degrees F. But that challenge is rewarded by the 65- to 100-foot visibility that these pristine waters offer. Our first dive is on the PLM-27 — acronym for Paris-Lyon-Marseille — a steamboat that operated under the Free French Forces of General Charles De Gaulle during the Second World War. Shallowest of the four Bell Island wrecks, the nearly 400-foot PLM, which has a tonnage of 5,319, sits upright in between 50 and 100 feet of water.

The shot line guides me to the shallow deck. Despite a torpedo blast amidships and iceberg scouring on the upper decks, her superstructure is well preserved. I descend onto the bottom and follow her portside all the way back to the stern. Slowly she takes form — it’s the massive propeller I am looking for. The PLM-27 is the only one of the four wrecks with its propeller in place, truly an astonishing site. Its curvature seems to awaken the steel mass, as if it were about to lift the ship off the bottom of the bay in time to escape its ill-fated destiny on that November day in 1942.

Rene LipmannRose Castle is the deepest of the Conception Bay wrecks, from around 115 feet to 165 feet.

During the Second World War, the battle for the Atlantic reached the far eastern shores of Canada — with it came German submarines, wolfpacks in search of Allied convoys. Four big steam-powered ships anchored in Wabana harbor at Bell Island, loaded with iron ore for the Allied forces. On September 5, the first torpedo penetrated SS Saganaga. The PLM-27 was the last to go down. That day 69 young seamen lost their lives.

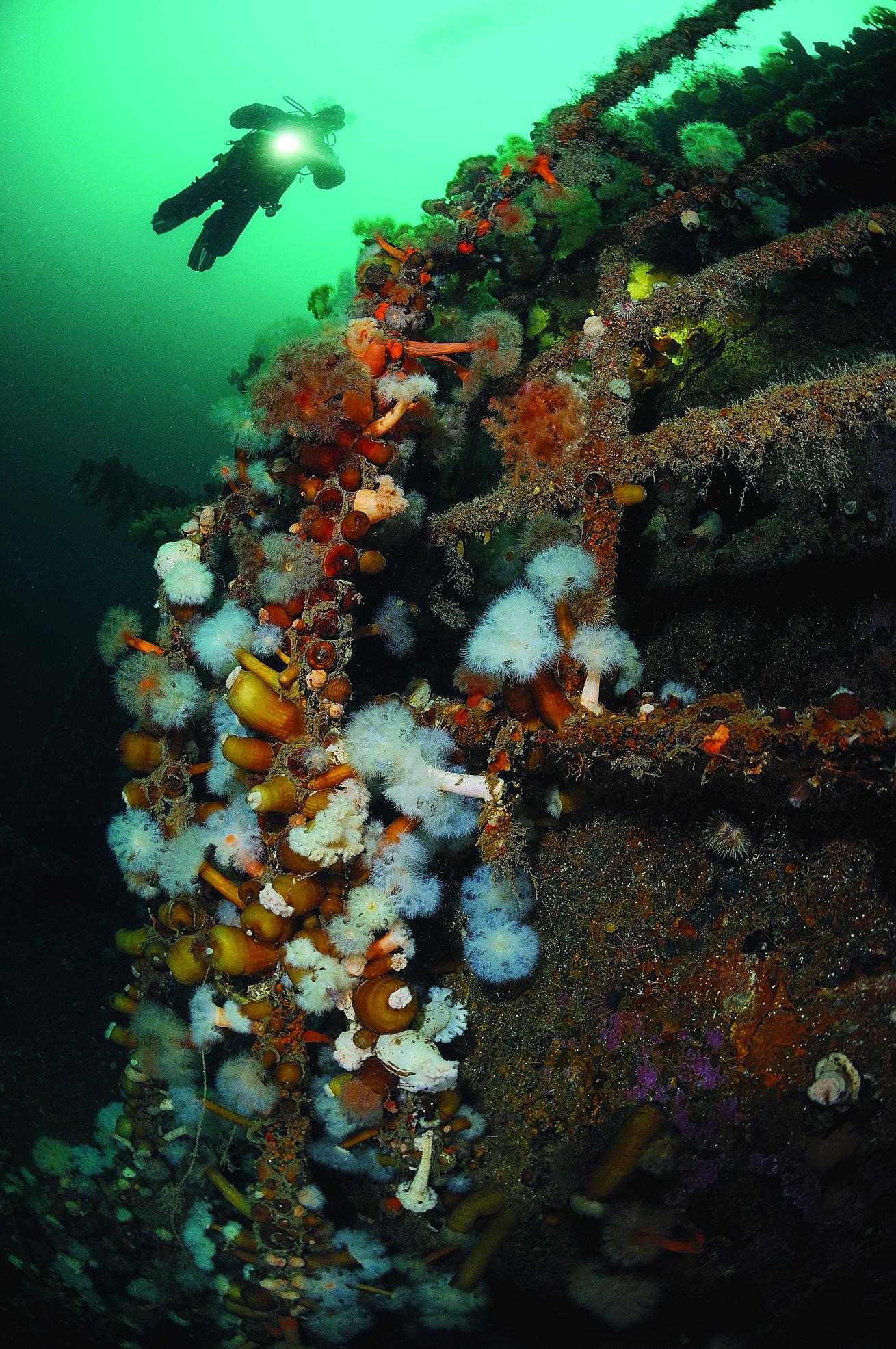

Rene LipmannNewfoundland's wreck diving offers plenty to explore.

SS Rose Castle — an impressive 459 feet and 7,546 tons — is bigger than its sister ship. Fully intact with exception of a torpedo hole, its bridge rises from the depths. The deepest of the four, its upper deck starts at around 115 feet, descending to the seabed at nearly 165 feet. Surprisingly, the ship is a haven of life, its metal frame covered in colourful anemones and sea stars. Crustaceans and small fishes cluster around hiding places, and even soft corals claim a niche, forming a surreal contrast with the decaying rigging and leftover ammunition.

Like the PLM-27, the SS Rose Castle stands vertical on the ocean floor. Despite its lack of propeller, the superstructure is breathtaking. From a distance both bow and stern overwhelm me; I have never been intrigued more by a wreck. A heavy stern gun is positioned on the back deck with bullets lying next to it. We hover above the stern until no-decompression limits force us up to the towering bridge. Inside a Marconi radio embodies the cries of agony of 1942; even the manufacturing plate is still present. Not until our safety stop do I notice the cold; we dove well over an hour, our computers reading not much below 40 degrees F. Back onboard Flaherty provides hot moose soup to warm up. Quietly we enjoy the delicious warmth and intense experience.

Rene LipmannScarface displays his namesake injury.

Stanley maneuvers the large pick-up off the ramp with ease and launches the Zodiac. We have arrived, after a three-hour journey north, in the Terra Nova National Park. Here the North Atlantic Ocean intrudes via small inlets into the land, creating an area for wildlife protected from the open sea. The surrounding evergreen boreal forest is home to moose and brown beers with numerous bald eagles circling high above the trees. We are here to search for a Beluga whale recently spotted near one of the fish farms. But when no white whale is found, we decide to stop searching and explore the environment. With canoes we glide through the clear water and paddle in one of the many coves. We spend the afternoon fishing and gathering blue mussels for dinner until the sun drops below the horizon, signaling it’s time to head back.

The next day we travel to Dildo, a small settlement that dates back to 200 B.C. known mostly for its cod, seal and whaling industry. The latter ceased after a 400 year tradition when whaling was prohibited in 1972. It’s unknown how the town got its name, though it has brought some notoriety and forms an attraction for tourists.

Rene LipmannThe radio room on Rose Castle.

By the harbour next to an old factory, we gear up for the dive. The concrete pier gives us access to a small beach where we enter the cold water. In the shadow of the dock nothing seems alive, which adds a special poignancy to our dive. We are looking for a whale carcass. Scattered over the harbor floor like discarded pieces of a giant puzzle lies large pieces of bone, a spinal cord. It’s unknown what species these belonged to. Not only were humpbacks hunted here but also blue, fin and minke whales. The bones look slightly soft and greyish, with few fish seeming to find residence in this hidden graveyard. The landscape feels barren and desolate; when the cold really starts to seep in, it’s time to go. This solemn place makes me appreciate even more the majesty of these amazing creatures when next I see them alive.

After a vibrant night of Irish music, dancing and drinking screech — the local hooch — at the George Street Festival in St. Johns, we are sad to find our trip is coming to an end. But before we leave Stanley has yet another surprise. Together with Holly Hogan from the ecological reserve Baccalieu, we leave for Avalon’s most northern park.

Rene LipmannPLM-27 is in less complete shape, but its propeller is intact.

Close to the shore, Baccalieu Island is one of the biggest nesting grounds of puffins, Jan-van-Genten and petrels in the world. The waters are full of capelin, a small forage fish found in Atlantic and Arctic waters, attracting whales and dolphins. When the whales hunt they form nets of bubbles to drive the shoals to the surface.

At last Stanley turns his boat into a smaller inlet, protected from the open ocean winds. Fortune is with us, as a mother and calf rest after a hunt. Gently we glide into the water to approach the pair; we want to be as careful as possible. Soon the humpbacks disappear, but just as I thought they had dived, mother and calf surface at just an arm’s length. For the first time I look straight into the eye of a whale, and the whale seems very aware of my being. It is a very strange experience. No longer am I more than an animal, no longer is she more animal than I. Completely overcome, when my buddy joins me I don’t notice that the whale passed minutes ago. We laugh. It is going to be very hard to top this.