Meet the Underwater Photographers Behind Scuba Diving Magazine

Who are the women and men behind the shots that amaze and inspire us each month in Scuba Diving magazine? Five of our favorite underwater photographers reveal the sweat, secrets and passions that put them where they are today.

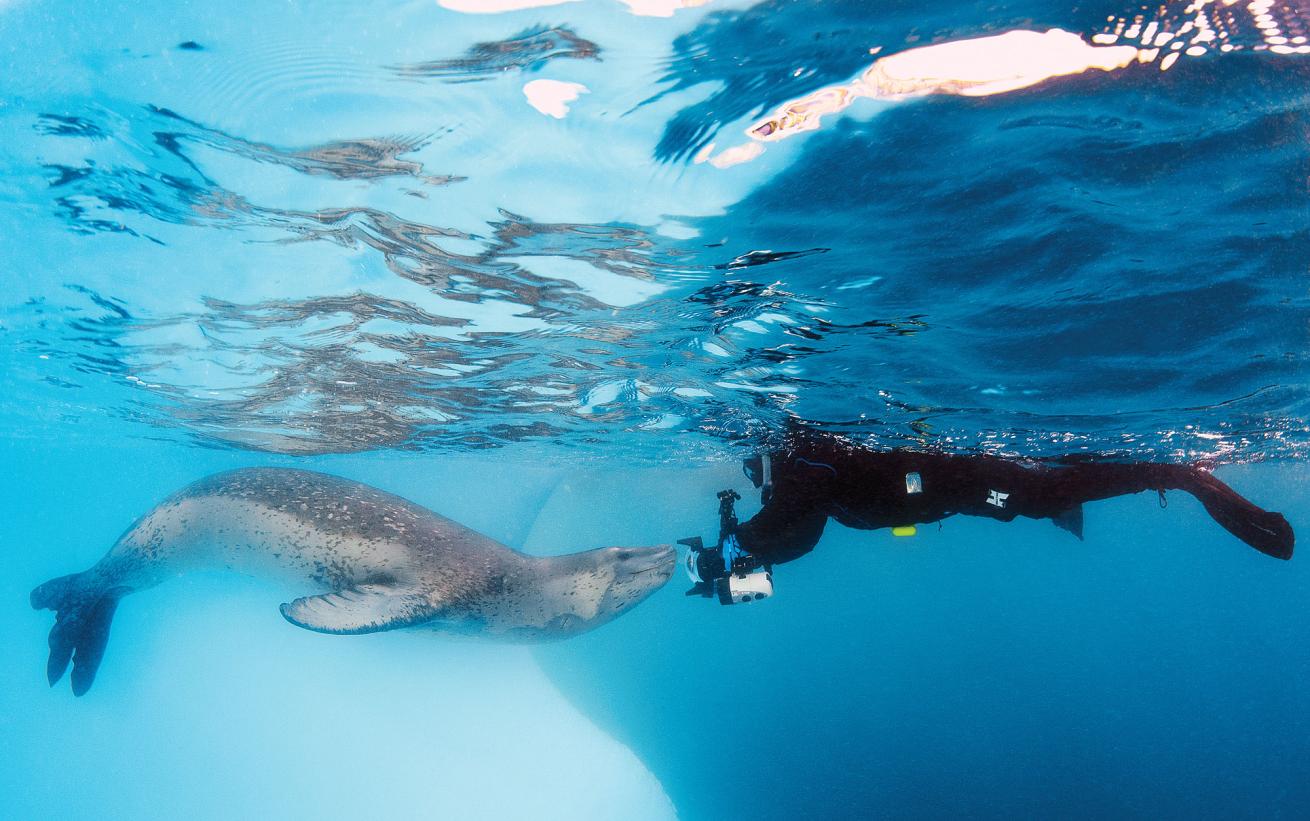

Steve JonesHow does Steve Jones get a shot like the Antarctic leopard seal? Be there, be ready and push yourself, he says.

Becky Kagan Schott“I jumped into one of the hardest environments — learning to shoot essentially in the dark — because I couldn’t afford to go out on boats all the time.”

The Extreme-Conditions Shooter: Becky Kagan Schott

Becky Kagan Schott, a National Geographic photographer and four-time Emmy Award winner for the CBS documentary Cave Diving: Beyond the Limit, credits her career in part to “happy mistakes,” images she took starting at age 12 as she explored the caverns, springs and, later on, caves near her hometown of Orlando, Florida. At the time, her only goal was to show friends and family what she was seeing.

“I jumped into one of the hardest environments — learning to shoot essentially in the dark — because I couldn’t afford to go out on boats all the time,” says Schott. Her education continued in the field, and in the high school photo lab.

Then another happy accident came.

“I happened to focus on a hood and, in another shot, a light that said Dive Rite, and I saw I could concentrate on logos and sell those images to gear manufacturers,” she says of her earliest image sales. “That gave me a jolt. I saw I could possibly make a career of this.”

Becky Kagan SchottCaves are king for Becky Schott.

From there, Schott interned as a photojournalist for a local TV news station, documenting everything from politics to hurricanes to alligators trapped in pools. “I walked into situations where I had no idea what I could be shooting. That run-and-gun style is so applicable to what I do now, where I don’t always know if conditions or marine life will cooperate,” she says. She learned that those adrenaline-charged moments were her thing.

“Now I specialize in shooting extreme situations — mainly caves, deep dives and shipwrecks,” she says. “I really like to focus on exploration.”

Schott is also quick to point out that a lot of her work takes place in her backyard; she calls Pennsylvania home and dedicates countless hours to the Great Lakes. “It’s the discovery factor,” she says. “Not everything in the Great Lakes has been found.”

A few years back, she was on the Alice E. Wilds, in 260 feet of 37-degree water.

“It’s so humbling to see something more than 100 years old that nobody has photographed since it went down,” she says.

And most recently, she’s been involved with National Geographic, collecting footage for its new 360-degree experiences, in which theatergoers will be entirely immersed in every angle of a scene, blown up to 40 feet tall. “I never thought my career path would take me here. It’s just surreal.”

Greg Lecoeur"Photography is art in that there are no rules, and the only important thing is to shoot what you like."

The Artist — Greg Lecoeur

For French shooter Greg Lecoeur, the most important part is the art. “Photography is art in that there are no rules, and the only important thing is to shoot what you like,” he says. “Because if you like your photo, other people will love it.”

For Lecoeur, that’s proving true, especially in the case of a shot he took of South Africa’s legendary Sardine Run, the 2016 National Geographic Nature Photograph of the Year. Its stars aren’t sharks, dolphins, whales or any other big hunter that most divers cross the globe to admire, but gannet seabirds. That’s because Lecoeur keeps an eye on everything happening around him, not just what he expects to see in the viewfinder.

“I’ve always been curious about everything in the sea,” says Lecoeur, who took his first photos at age 15 of the French Mediterranean. At the time, shooting was a lark. But it was also the thing missing from his life at age 32, when he sold his electronic-scale company, sublet his apartment and traveled the world with his scuba-instructor card in his pocket. For a year, he dove, filling his portfolio with images from the Galapagos, Hawaii, Bahamas, Mexico’s Yucatan and Baja peninsulas, and British Columbia. Those images were noticed by a handful of magazines, including Scuba Diving.

“They gave me a chance,” he says, and that led to more assignments, and more awards. Through it all, his mantra hasn’t changed: You must love your shot. “The other thing is that you need to enjoy the time when you are taking the photo,” he says.

In May, Lecoeur was in South Africa to visit friends. He figured he’d devote a day to hopping in with mako and blue sharks. On the ride out, the group stumbled upon a pod of dusky dolphins.

“I asked the captain if I could jump in and just try,” he says. “Then I was surrounded by 200 dolphins — my fish-eye lens was too small to capture them all.” It’s a common theme in his images.

“All my best photos happen when I’m not really expecting it.”

Greg LecoeurGreg Lecoeur captured this lemon shark at Tiger Beach in the Bahamas.

Viktor Lyagushkin"No matter what happens, you are responsible for everything. If your camera doesn't work, it's your fault."

The Leave-Nothing-To-Chance Workhorse — Viktor Lyagushkin

Luck — some might call it bad luck — landed Viktor Lyagushkin in the role of full-time underwater photographer. He’d been a magazine layout designer until 2010, when he took on a project to document the wonders of Russia’s Orda Cave.

“That book took so much time that we lost our jobs,” says the now-National Geographic staff photographer of the project that consumed him and his wife, writer Bogdana Vashchenko. But the pair quickly rebounded. Lyagushkin’s Orda Cave images on Flickr led to thousands of image-requesting emails a day. He stayed busy.

Of his work to date, he’s most proud of shots from the Baltic Sea in 2015. “Everybody believed it wasn’t possible,” he says of obtaining photos of shipwrecks in 100 feet of green water — so murky that 10 feet of viz is considered a good day.

Lighting proved the biggest hurdle. “If you use strobes or torches to shine on the object, you see so many particles that it looks like yellow milk.”

Instead, he relied on lights held by assistants. Editors were immediately wowed, sending him back for more. And that is why Lyagushkin stays in demand: He doesn’t see obstacles, only shoots that require more planning, more creativity.

For project #Seagull, he envisioned freediver Natalia Avseenko flying over algae-covered pines in a quarry outside Nizhny Tagil in Urals, Russia. Avseenko was costumed in a blue dress and white veil, weighted so she could run across the quarry floor. But the weight also kept her from reaching the surface easily, and thus teams of safety divers were needed. In addition to extra hands, Lyagushkin hauled in three cameras, extra assistants and extra gear. “No matter what happens, you are responsible for everything. If your camera doesn’t work, it’s your fault.”

Having a backup of everything can make the difference between whether or not a photographer lands a next assignment. It’s this adherence to a deep sense of responsibility that has made Lyagushkin such a fast-rising star. “This is also why we are able to do such impossible things.”

Viktor LyagushkinA project on Russia's Orda Cave was what led Lyagushkin to become an underwater photographer.

Steve Jones"The important thing is that you're in these environments, ready and pushing yourself, because eventually you will get the shot."

The Quick-Draw Hustler — Steve Jones

Steve Jones couldn’t stop buzzing the week he spent on the island of Vis, Croatia. Prior to the trip, the Oxfordshire, England, native had confirmed the location of a B-17 Flying Fortress sunk during World War II. At 236 feet, the plane had been witnessed by a mere handful of divers, and even fewer photographers. “All week I was excited — I knew my life wouldn’t be complete without this dive,” says Jones. “I had one dive, and 20 minutes. I knew I had to work quickly.”

The result was soon nominated for the U.K.’s Underwater Photographer of the Year contest, and although Jones didn’t take first, recognition came with another reward. Co-pilot Ernest Vienneau had been declared MIA following the 1944 crash; his family never knew his fate. Until Vienneau’s nephew saw Jones’ photo and emailed him. “To see the joy that family expressed and what that image meant to them was hugely rewarding,” says Jones. “It was one of the defining moments of my career.”

That began for Jones at age 8, when his grandfather taught him the workings of a camera. At 14, Jones was scuba diving. He worked first as a scuba instructor, then a guide for underwater photographers, then a teacher of underwater photography.

His career as a dive-magazine shooter happened quite by accident. The German publication Unterwasser sent a journalist to where Jones was working, but the photographer didn’t show up. That was Jones’ first sale to a magazine, one that he still works with 21 years later.

On a shoot in Antarctica, Jones found himself in the water with a leopard seal that didn’t know the meaning of personal space, lunging within inches of the lens and retreating. Ever the pro, Jones relied on a trick or two. “I quickly flipped the strobe arms in close, knowing I would get coverage if the seal came in close, which it did. And then I prayed.”

Says Jones: “For every shot that works out, there are many that don’t. The important thing is that you’re in these environments, ready and pushing yourself, because eventually you will get the shot.”

Steve JonesJones' history of shooting deep wrecks includes the Empire Heritage at 220 feet.

Brandon Cole"I just go out and spend a lot of time outside, and nature does most of the work."

The Big-Picture Realist — Brandon Cole

“I call it my Top Ramen era,” says Brandon Cole of his early days as an underwater photographer. He gave himself two years to make it, selling a car and a motorcycle to foot the expenses of traveling the West Coast — Alaska to Mexico — diving and shooting. Luckily, Cole knew to keep expenses low, sometimes spending a grand total of zero dollars per day. “I would camp in little remote villages like Kake in southeast Alaska, at times spending the night in the parking lot of the boat marina, which was cheaper than paying for a campsite,” he says. The lifestyle was born of Cole’s understanding of budgets. He never deviated, then or now, from avoiding overspending, or from knowing his worth.

“I remember arguing with a publisher back in 1993,” he says. “They tried to convince me that because I was new, I should give them my photos for free to get my foot in the door. That I should be more concerned with that than payment.” Cole wasn’t having it. He chose this career because he wanted “the freedom to decide what I was going to do, and how to pursue my connection to the sea.”

And to enjoy the freedom to make choices, one needs money. This desire is so clear to him that it makes decision-making easy. After graduating with a degree in marine biology, he walked away from a career in science because he didn’t want to log days in the fluorescent lights of the lab. Since he’d already made that hard choice, it was easy to say no to giving his work away for free.

It paid off. For 25 years, Cole has succeeded as an underwater shooter, becoming one of the biggest names in big-animal photography. He was nearly bitten by an oceanic whitetip off the island of Kona, Hawaii, and, on another trip, was pinned down by a right whale off Patagonia, Argentina.

“I was terrified, but also rather amused,” he says of the snorkeling experience that ended with him stuck on the bottom, 18 feet down, until the whale’s curiosity abated and Cole could breathe again at the surface. He’s quick to add that his interests far exceed sharks, dolphins and orcas. He also has a soft spot for shooting nudibranchs and other macro life, as well as, well, everything.

But it’s megafauna that helped establish Cole in the dive community, perhaps most so following the publication of a shot of a killer whale leaping from the Pacific Ocean, taken from the skiff Cole was using at the time as his work boat. “I saw that shot as a smart business decision,” he says. “Few of my colleagues at the time were willing to put the time into topside photography.” That photo went on to grace the side of airplanes and beer bottles.

It was a winner because Cole knows what he’s doing, sure, but also because of dogged effort, working all the angles and shooting long after he thinks he has a good shot.

“I just go out and spend a lot of time outside, and nature does most of the work.”

Which — when it comes to his workplace — is all he ever wanted in the first place.

Brandon ColeBrandon Cole's eye for megafauna put him on the map.